Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Interview with Chris Anderson: “Technology is not important. What’s important is participation”

January 25, 2013 12 min read

I recently had the pleasure of talking to Chris Anderson over the phone, for Novedge's series of interviews with artists and innovators. I am a big fan of Chris's books and Novedge fits perfectly in his Long Tail business model . For those of you not familiar with Anderson, he is a writer and the founder and chairman of 3DRobotics, a robotic manufacturing company. He was also the editor of Wired from 2001 to 2012.

Novedge: I'm a huge fan of your books and really enjoyed Makers. My first question for you is: How would you define yourself? You're an entrepreneur, you're a writer. How do you describe what you do and who you are professionally?

Chris Anderson: I try to avoid that question (laughter) I do a lot of things. I try not to come up with any single label. I'm a CEO. I'm a boss

Novedge: One thing I'm curious about is how you became passionate about writing about trends and the future. What lead you to it?

Chris Anderson: I have been very lucky to be around people who were kind of doing the same thing. I was lucky to grow up with a family who encouraged kids to be thoughtful about where this is going and where you should go, and to be exposed to a kind of analytical culture in my family. Then I was lucky to work in places that encouraged that first at Nature and Science and then at Wired. Wired is a publication very much about ideas and trends, from science to future technology.

Novedge: How did you first come into contact with 3D printing?

Chris Anderson: I heard about Makerbot and I happened to be in New York shortly after they started. I asked to get a tour, went to Brooklyn and walked through the facilities. I ended up buying their 3D printer on the spot. I bought #380 and that was mind blowing. I put it together and it didn't really work very well but the next one I got worked great. And the rest is history.

Novedge: What's the favorite thing that you printed on your Makerbot?

Chris Anderson: I wrote about it in Makers. We printed a lot of things but the thing I actually like the most was furniture, you know, items that I do with my daughters. The things I design myself are pretty cool but I'm not a very good designer, so the things that we download from Thingiverse and print out, those are the ones that print so well. So, yeah, I like the furniture the best.

Novedge: Let's talk about how hard it is to use the printer and the software. Do you see regular people learning how to use the software or do you see more people downloading the designs and printing them at home? How hard do you think it is to use this technology, if you don't already work in a tech field?

Chris Anderson: It used to be very hard and now it's getting incredibly easy. So now my children do this. They don't need me anymore. They use Tinkercad on the web, which is super easy for kids, but also very powerful. So, by and large, it's not really any harder for them that using Word software and printing paper. It seems very natural to them. Again, three years ago this was super hard but now it's literally like regular printing.

Novedge: Apart from Tinkercad, is there any other software that you would recommend or that you love to use?

Chris Anderson: It really depends on how sophisticated you want to get. The kids use Tinkercad and I actually prefer it for most of my stuff. When I want to get a little more complex, I switch to Autodesk 123D and then in the office, professionally, we use AutoDesk Inventor.

Novedge: There are companies out there, like Shapeways, where you can get a design or you can order something already 3D printed. Is there one you like the best? Do you wish they did something different?

Chris Anderson: We use Shapeways all the time. About every week we send them something. What we use Shapeways for is the material that we can't touch at home, like metals. Shapeways's printing service is very easy to use, but it takes quite a long time, it can take a month for something to arrive. Ideally it's a little bit less than that. So you have to wait. But when it shows up, it's absolutely beautiful. We actually don't use designs that are already on Shapeways. I don't know why but we don't. We tend to use or create our own designs or download them from Thingiverse and then send them to Shapeways.

Novedge: What do you like the most about Thingiverse?

Chris Anderson: I just love the variety. My favorite designer there goes by the name of Pretty Small Things. She's a theatrical set designer on Broadway but as well as designing sets she puts these designs on Thingiverse and they're beautiful. So yeah, I just like the variety, I like the creativity. It's just there's always something new and cool there.

Novedge: I read your book Makers and you talk about being an inventor vs. being an entrepreneur, how before it was hard to be an inventor and an entrepreneur and now things have become a little bit easier.

Chris Anderson: The process to go from invention to market is a two-part step. The first was to go from idea to prototype, and that used to require skills, machine skills, manufacturing skills, fabrication skills. And the second was to go from prototype to production and that required understanding, having access to mass production capacities and all of that. Both of those have now gotten much, much easier. Obviously a 3D printer is a great way to go from idea to prototype and likewise for a laser cutter or any of these technologies. So you don't need machine skills to go from idea to prototype. And then to go from prototype to production is increasingly easy as well because of so-called cloud manufacturing. Those same files that you design on screen and send to your 3D printer, you can upload online. Manufacturing companies will take those files and mass produce products for you any way that you want. It's sometimes a little more complicated than that, depending on the product. But fundamentally, regular people have access to both prototyping and manufacturing, which was not the case when my grandfather was inventing things.

Novedge: Are we all entrepreneurs? Are we all inventors?

Chris Anderson: No, no, I don't think so. And that's fine. I think we are all creators in some way, but I don't think it's necessarily in everyone to become an entrepreneur. I think that one percent of people could design and innovate and everybody could start playing with their creations. Let's say most people do nothing but print other people's designs or distribute them, or customize them. Let's say most people do nothing creative with it: but one percent do have their own ideas or do invent something, or innovate. And let's say one percent of them decide they want to become an entrepreneur. That's one out of a thousand.

Would you say that that's a failure? You know, only one out of every thousand of these people becomes an entrepreneur. There are 300 million people in this country – that's when you realize that 0.1 percent is a very large number. It means you've got thousands or tens of thousands of new entrepreneurs, new manufacturers, new product categories, new products themselves that are entering the market that wouldn't have existed otherwise. And that feels very much like the Web, which basically gave everybody the power to publish and, you know, lots of people did nothing more than update their Facebook page but some people created Facebook. The lesson of the web is that the most innovative ideas, the most energetic entrepreneurs, typically come from outside the traditional industry. This is the first time that has been allowed to extend to manufacturing as well.

Novedge: I like the comparison that you made between the internet and 3D printing, this revolution in manufacturing. What are the advantages of actually having more people participate in making products? What are the benefits to society?

Chris Anderson: What we're talking about is what is called democratization. Personal computers democratized computing, the internet democratized communications and now we're democratizing manufacturing. Any time you democratize, you're basically bringing more diversity, more people, more ideas, more contexts to development. What you find is that typically most people are "amateurs", they're not professionally trained and they don't have credentials, they don't have work experience, they don't work for companies that are in the space. And yet, when you look at everything exciting on the web it was all created by people who were initially amateurs. When you look at the biggest web companies today, they were all started by people in colleges, more or less. And they weren't working for IBM when they created these products. They were working for themselves, or maybe not working at all. They were students or they were just users and they had ideas. Now, maybe they were only one out of a thousand or whatever, just a tiny fraction of people have those skills, but because democratization increases the pool of participants so hugely, that small fraction of geniuses creates a huge new pool of talent that wouldn't otherwise have been tapped. So it's simply that geniuses are hard to find. Great ideas are hard to predict, and the best way to do it is to increase the pool of participation so much that the geniuses will emerge.

Novedge: Would you say that it also equalizes the playing field a little bit? We are removing barriers to education and access to capital.

Chris Anderson: Yeah, very much. I think the combination of these tools and these web services and sites like Kickstarter, which brings access to capital to everybody with a good idea, are all leveling the playing field and lowering the barriers to entry. That's exactly what the web and open source software did and it works. Every important trend in technology over the last three decades has been essentially to lower the barrier to entry to participate. Some of the barriers were cost, some of the barriers were permission, some of the barriers were complexity, some of the barriers were community. As all of those things fall, people suddenly start doing stuff. They start acting. They start creating products and companies. People think that technology is important. Technology is not important. What's important is participation. When technologies work it is because they make it easier for people to participate. And I don't have to predict this any more. It's 2013. We are 40 years into the personal computer era. We are 20 years into the internet era. We are seeing what's happening and this is just the next chapter in that story.

Novedge: Companies are starting to hire differently, they're starting to have a different culture inside. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Chris Anderson: 3DRobotics is an open source community and also a company and so we are a traditional company in one respect, where we have employees who have roles and responsibilities and we create products. But we are also a community in the sense that we have an open platform that allows tens of thousands of people to participate and volunteer and create. Traditional companies do it all themselves and we share the function between professionals and amateurs, between employees and amateurs and engineers, between the closed and the open. So that's my company, that's the way we're structured. I wouldn't say that all companies should be structured that way. I'm sure most companies aren't structured this way but it is certainly one of the lessons from the open source movement that this sort of cross sourcing in a process can create the kind of sophisticated product that people thought could only be created by traditional companies. Turns out that a well-constructed community can be a powerful innovation driver. That's something I think all companies need to pay attention to, but it might not be appropriate for everybody.

Novedge: How different is it now to finance your project? Can you say something about Kickstarter and the impact it is having on the industry?

Chris Anderson: I think Kickstarter is really the final element that completes the industrial revolution of the maker movement. It lowers the last barrier, which is the access to capital. It does three miraculous things. The first is that it moves money forward in time. It moves money from the end of the process, when people buy a product, to the beginning of the process, when you actually need to invest in R&D and production tooling. So simply the act of taking presales and getting the customers to fund the product is terrific because the customers are ultimately the decider of whether it will be a success. The second thing it does is that it builds a community around the product so that lots of people pre-order something and they become invested in the success of the product. They want to promote it, by social media or otherwise, and they want to participate in its design and give feedback.The community is a very important marketing tool, to say nothing of a feedback tool, and using that tool improves the product before it comes to market. And finally, Kickstarter does market research. If the product fails on Kickstarter it probably wouldn't have survived in the market. Move on to something else. In a sense it "de-risks" a product. That's one of the hardest things to do in traditional industries and it's what Kickstarter was designed to do. Anybody can do it. And I think that's the last barrier. A bunch of other sites are doing the same thing and it's not perfect. We are seeing that some people are realistic about what it takes to get a product from prototype to production, and some aren't. But by and large it is less risky than traditional startups. So, I'm really enthusiastic about it.

Novedge: In Makers, you talk about the "happiness economy". You write that basically, once we achieve a certain standard of living, we are not motivated by more money necessarily, we look for more meaning.

Chris Anderson: I did talk about that. That's not my specialty. There are many other people who know way more about it than I do, but when I look at communities where the participation is open like our own, they are rarely driven by money. They are mostly driven by passion, by what we call scratching your own itch. Paychecks ? That's great but it turns out people are doing amazing things as volunteers, driven by passion. And what you give them is a platform and opportunity to act on that. To take the passion and turn it into something that's shared, something that's a tribute to something bigger than themselves and inspire other people to follow their path. My previous book Free was all about that, about the non monetary economy. Meaning is another word, passion is another word. Connection. These are all forces that drive us to do things and when you think about it, most of our interactions with people are not done for money. Most of what we do is driven by non-monetary forces and to be able to turn those powerful social forces into an economic force just by harnessing passion, that's the opportunity here. So I think that the more control we have over our lives, the happier we are. That's kind of the big lessons. Fundamentally what people want is a sense of knowledge and meaning and certainty and all the things that come with it. To the extent that we can extend that to the products all around us, the sense that we can be more involved in their creation and use, the happier we are. Take food for example: wanting to have a connection to something as important as the food you eat makes you less of a passive consumer and more of an active participant . When you look at the people who are going to Farmer's Markets and buying local, there's a reason why what they want to know about the origins of these products. They want to have a connection to the community. They want to feel that there's more than just a product they're consuming, that there's a movement they're supporting or a story that they believe in or a value that they share. And that relationship with our goods is something that you are seeing across the board. It's just one of those things that emerges out of developed economies and I think that we now have the potential to take that beyond food and textiles to more sophisticated manufacturing goods around.

Novedge: Do you think the same will happen in manufacturing?

Chris Anderson: Yeah, I'm speaking to you in my office in Berkeley, which is next to a furniture design company, called Swerve. We're here in California but California is not a low cost labour market. And yet, they're making furniture. How do they keep on making furniture? The reason that people buy it, and pay more for this furniture, is that they feel that it's a superior design. And the reason they feel it is a superior design is that they see the designers. They talk to the creatives. They understand the process and they value the culture that this design came from, because it's their culture. It's shared.

Novedge: I have one last question. What advice would you give our readers about moving forward with the democratization of manufacturing?

Chris Anderson: It's hard for me to give advice to your readers because they already know a lot of this stuff. My breakthrough was not so much doing it myself but doing it with my children. When we brought a 3D printer home and started showing the children how it worked and using the tools, their own creativity emerged and that really encouraged me: if children could do it, anybody could do it. A lot of your readers probably have 3D printers at work. I would encourage them to consider a 3D printer at home. If they have children, a child growing up in a house with a 3D printer is a child that can imagine something and then can make it for real. And that's a powerful lesson. Some of them are going to become the adults who are the designers of tomorrow. It's an inspiration that my generation grew up with a home computer and we created, you know that generation created our web. This generation may grow up with a 3D printer and this generation can create the new industrial revolution

To learn more about Chris Anderson, visits DIY Drones and keep in touch with him on Twitter.

Makers by Chris Anderson is Novedge's Book of the Month.

Related articles

Also in NOVEDGE Blog

Enhance Your Designs with VisualARQ 3: Effortless Geometry Extensions for Walls and Columns

April 30, 2025 8 min read

Read More

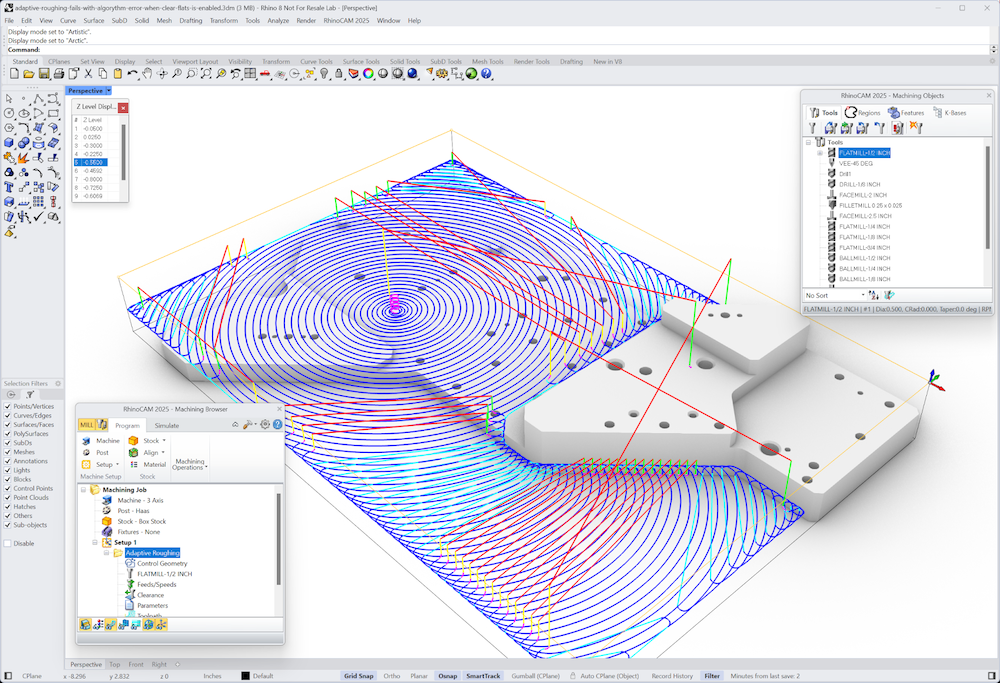

MecSoft Unveils RhinoCAM 2025 and VisualCAD/CAM 2025 with Enhanced Features

March 08, 2025 5 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …