Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

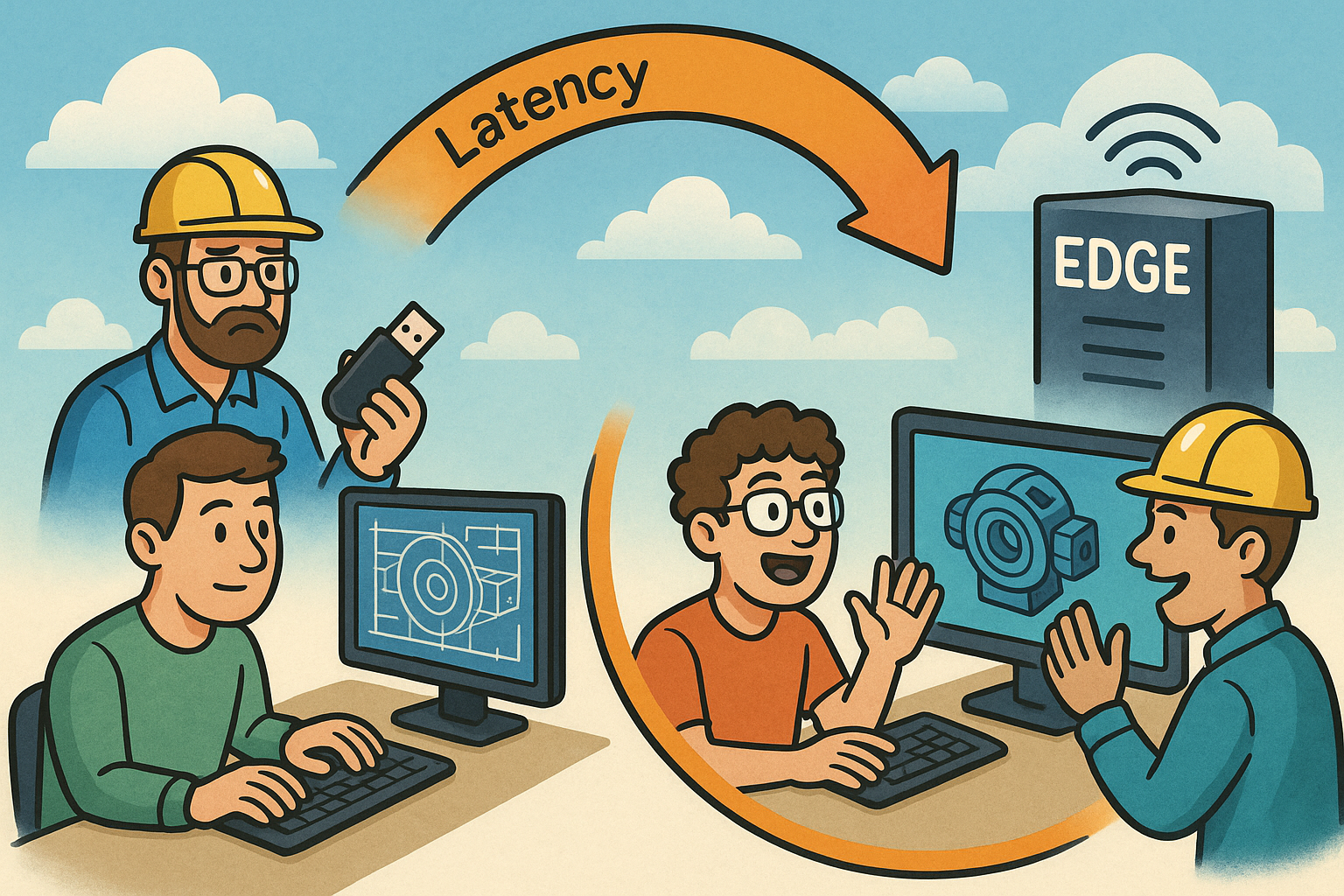

Design Software History: From File-Shuttling to Edge: The Latency Evolution of Collaborative CAD and Real-Time Visualization

December 11, 2025 13 min read

Historical context and the latency problem in CAD collaboration

From file shuttling to live sessions

The story of collaborative CAD has always been a story of round-trip time. In the 1980s–2000s, engineering teams coordinated through drawing-centric workflows and check-in/check-out discipline enforced by PDM/PLM vaults such as UGS Teamcenter (later Siemens Teamcenter) and PTC Windchill. A designer would lock a part file, make edits in Pro/ENGINEER, CATIA, or Unigraphics/NX, and then release the lock so the next person could take a turn. When different CAD systems had to interoperate, geometry moved as IGES or STEP, usually by email or FTP, with all the attendant headaches of tolerance drift, lost parametrics, and layer conventions. This was collaboration by procession rather than interaction: a baton-pass. The result was predictably high-latency decision cycles, with overnight exports and morning reviews that dampened momentum and encouraged local copies to proliferate.

By the 2010s, cloud-first approaches upended those rhythms. Onshape, created by Jon Hirschtick and team after their SolidWorks chapter, pushed multi-user, in-browser editing that collapsed hand-offs into a shared, server-side model. Autodesk advanced Fusion and Autodesk Platform Services to connect modeling, simulation, and CAM to cloud data, while Dassault Systèmes rolled 3DEXPERIENCE into an end-to-end platform. Critically, these systems began running server-side modeling kernels—Parasolid (Siemens), CGM (Dassault), and ACIS (Spatial)—so that feature evaluation and B‑rep topology lived next to the data, not on laptops. Collaboration became live, but this exposed a hard limit: the cloud is not magically near; when a feature regenerates across an ocean, human patience meets physics. That realization paved the way for the next shift—putting compute where collaborators actually are.

Why latency matters in CAD

CAD feels interactive only when constraint solvers, sketchers, and assembly mates respond in less than a blink. Practitioners target sub-100 ms round-trip for dragging sketch geometry, solving mates, and scrubbing feature parameters. Drop below that, and cursor motion feels “sticky,” feedback becomes coarse, and users compensate with slower, more discrete manipulations that reduce design flow. For AR/VR, the bar is stricter: motion-to-photon under ~20 ms is the norm to avoid discomfort, with head-tracking and late-latching that leave little room for network slop. Centralized clouds, particularly when a team spans regions, often deliver 60–150+ ms RTT before any solver time or encoding overhead. That is acceptable for file-based PDM operations and asynchronous reviews, but painful for live editing or streamed rendering during a tense design review with an executive watching the parts flicker.

- Human factors: delays beyond ~100 ms break the hand–eye control loop that underpins precise sketch edits and mate tuning.

- Systemic contributors: DNS and TLS handshakes, TCP slow-start, server-side solver steps, and encoder buffering accumulate non-trivially.

- Content complexity: large assemblies trigger collision detection, kinematic constraints, and LOD swaps that amplify jitter if they’re distant.

- XR constraints: reprojection hides a few dropped frames, but network variability still shows up as “swim” and reduced presence.

When latency stretches, users change behavior: they avoid fine-grained editing, add excessive mates or fixed constraints to “lock” assemblies, and defer exploratory modeling. That behavioral tax is a cost in innovation. The design software community—kernel developers, ISVs, and platform teams—has learned that reducing mean latency is useful, but trimming jitter and securing deterministic frame pacing is decisive. In essence, the closer we shove stateful modeling and rendering to users, the more their hands regain the fidelity of a local workstation, even if the actual horsepower sits somewhere else.

Edge computing enters the scene

Edge computing addresses the gap between “cloud” and “close.” Telcos rolled out multi-access edge computing (MEC) with 5G, while hyperscalers introduced regional micro-datacenters—AWS Wavelength and Local Zones, Azure Edge Zones, and Google Distributed Cloud Edge—that place CPUs and GPUs in metropolitan points of presence. For CAD and visualization, these sites can host low-latency containers running modeling kernels and rasterization or RTX ray tracing, yielding a practical model where authoritative state lives nearby and synchronizes efficiently to a central source of truth. The goals are clear: reduce jitter, stabilize frame pacing, and place computation near factory floors, campus labs, and construction sites where adverse RF environments and mobile work devices dominate.

Technically, edge sites exploit NIC offloads, SR‑IOV, and GPUDirect RDMA to keep encoder pipelines lean and scene updates fast. They also allow data gravity to work in our favor. Rather than dragging geometry across continents for every constraint solve, small “edit deltas” and keyframe-like scene updates flow to a nearby node that holds hot context in memory. The central cloud maintains durable truth and performs heavy async tasks—global replication, background meshing, or long-run simulation—while “live” sessions stay close to human attention. Inside 5G footprints, radio scheduling and predictable backhaul can yield surprisingly stable latency budgets. In practice, this is a convergence: the cloud learns to be local, and workstations learn to be stateless. The most successful deployments boldly embrace the mantra: move compute to users; stream only what eyes and hands need.

Technical architecture—how edge accelerates real-time CAD and rendering

Data and geometry handling at the edge

At the heart of edge-enabled CAD is data locality for geometry. Modeling kernels—Parasolid, ACIS, and CGM—execute in containers or lightweight VMs pinned to GPUs at the edge, keeping feature trees, parameter sets, and B‑rep structures warm in memory. Instead of sending whole models, clients issue high-level operations (e.g., dimension changes, feature toggles, mate edits). Edge nodes apply them, invoke the solver, and return compact “edit deltas” to peers and to a central store. Those deltas are operation-oriented, not file-sized blobs, yielding excellent bandwidth efficiency and precise conflict scopes. When tessellation or presentation changes are needed, progressive streaming kicks in: tessellated levels of detail are updated patch-by-patch, compressed with Draco for meshes, and structured as USD or USDC layers to preserve topology and material bindings without bloating transport.

- OpenUSD is becoming the lingua franca for multi-tool scene graphs; NVIDIA Omniverse uses USD-based Nucleus to coordinate edits across applications.

- glTF serves lightweight viewers, mobile devices, and web contexts where a concise runtime representation is ideal.

- STEP AP242 remains the solid baseline for MBD-centric interchange with non-real-time systems, preserving PMI, validation properties, and tolerances.

To keep edge caches correct, content-addressable storage and hash trees ensure that identical geometry shards are reused across sessions. Versioning is explicit: USD composition arcs and variant sets capture multiple assembly states without duplicative payloads. On each node, a geometry service tracks hot and cold subassemblies, evicting distant context while pinning frequently manipulated components. The result is a system where edits propagate as small intent-bearing messages, visuals stream progressively, and the authoritative model in the central region converges via append-only logs. Designers get immediacy; IT gets auditability and resilience.

Real-time visualization paths

Visualization follows two complementary paths. The first is remote rendering: edge GPUs (NVIDIA L4 and A10-class parts, alongside AMD equivalents) render frames and encode them via NVENC with AV1 or H.264/HEVC. Low-latency transports—WebRTC over QUIC, NICE DCV, PCoIP/HP Anyware, and Citrix HDX/EDT—carry those frames with input events multiplexed alongside. This path shines for heavy scenes with RTX effects (path tracing, DLSS/DLAA denoising) and when IP must never leave the data center. It also aligns with XR streaming, where OpenXR clients can offload raster and ray tracing to “CloudXR”-style servers at the edge, reducing motion-to-photon and preserving presence during walk-throughs.

- Remote rendering: best when scenes are huge, materials complex, and devices weak; NVENC AV1 minimizes bitrate for a given perceptual quality.

- Hybrid assist: stream geometry and materials quickly, then let clients render locally with WebGPU/WebGL and variable-rate or foveated shading.

- XR streaming: late-latching, timewarp, and edge proximity keep head-motion cues consistent at 72–120 Hz.

The second path is on-device rendering assist: the edge streams geometry deltas, material packs, and light probes fast enough that a laptop, tablet, or headset can draw locally. With WebGPU, even browsers can handle mid-size assemblies at steady frame rates; techniques like foveated shading and variable-rate shading ration GPU effort to where the eye looks. Hybrid strategies often emerge: remote render during complex shading or when bandwidth allows; drop to client-side draw for input-critical interactions. Crucially, both paths benefit from edge proximity. Encoder buffers stay shallow, QUIC congestion control adapts quickly on metro networks, and frame pacing becomes predictable. The art is choosing the right mix per session—something orchestration layers can automate based on network telemetry and scene complexity.

Concurrency and conflict resolution

Collaborative CAD lives or dies on its ability to accept simultaneous edits without carnage. Edge-first systems structure all changes as operation streams: “add fillet,” “change dimension,” “reorder feature,” “modify mate.” Inspired by CRDTs and OT, these operations can be merged without central locks, with transform strategies that preserve intent even when order differs. To keep feedback snappy, constraints and mates are solved at the nearest edge node, with “speculative” local convergence that is reconciled globally via vector clocks or lamport timestamps. When divergence appears—say, two users alter topology around the same vertex—edge nodes escalate from optimistic merges to human-resolution workflows, but without stalling unrelated edits.

- Topology edits: feature add/remove, boolean changes, and face splits that alter the B‑rep graph.

- Parametric tweaks: dimension adjustments, equation updates, and pattern counts that can commute when scoped carefully.

- Assembly intents: mate redefinitions, kinematic limits, and reference substitutions that benefit from assembly-graph partitioning.

- Annotation and MBD: PMI notes, GD&T frames, and views that can merge CRDT-style with provenance intact.

Assembly graph partitioning is essential. Hot subassemblies—gearboxes under review, robot wrists under tune—remain resident at the closest edge, with precomputed kinematics and a collision broad-phase (BVH or spatial hash) ready for instant responses. Cold sections sit compressed or remote, only waking when navigated to. Deterministic solvers, seeded consistently with “sticky” IDs for edges/faces, ensure repeatable outcomes across nodes. The payoff is psychological as much as technical: users stop fearing collisions between edits and resume thinking in terms of intent. The system becomes a conversation, not a turnstile.

Orchestration and reliability

Edge is distributed systems in the wild. Kubernetes variants such as K3s and microk8s schedule GPU-enabled pods via device plugins, balancing sessions across nodes while respecting data locality. Autoscaling via HPA or KEDA responds to bursts—an afternoon review with a dozen stakeholders—by spin-up of additional renderers or solver pods. Yet the compute is only half the story; state must survive blips. Eventual consistency governs: local caches buffer edits, write-ahead logs capture intent, and periodic snapshots create restore points. If an edge cell partitions from the core cloud, users keep working, then reconcile on rejoin. QUIC’s connection migration handles client mobility; session affinity and STUN/TURN (ICE) bridge changing networks.

- Resilience: append-only logs (e.g., Raft-backed) plus CRDT scene layers prevent data loss during failover.

- Observability: per-session metrics for RTT, jitter, encoder latency, and solver time feed autoscaling and routing decisions.

- Security fabric: mTLS, short-lived tokens, and policy enforcement close to the edge, optionally via a lightweight service mesh.

Operationally, warm-start techniques slash user-perceived delays—pre-pulling container images, pinning models in cache, and pre-allocating NVENC sessions. Networking uses SR‑IOV and DPU/SmartNIC acceleration to reduce jitter, while storage sync employs tiered strategies: local NVMe for hot, regional object storage for warm, and cloud object storage for cold. Crucially, orchestration policies understand geography: a Paris user should not jump to a Frankfurt edge during a brief blip if local recovery is imminent. In mature deployments, the edge behaves like a heat-responsive membrane—elastic, local-first, and hard to surprise.

Industry landscape—platforms, protocols, and notable moves

Cloud CAD and collaboration pushing to the edge

PTC propelled cloud-native CAD with Onshape and the Atlas platform, championed under CEO Jim Heppelmann. Onshape’s multi-user editing architecture—born from the lessons of SolidWorks and built anew for the web—made a compelling case that simultaneous CAD is possible. As customer bases globalized, PTC introduced regional compute topologies that keep edit round-trips short, and partnered with network and cloud providers to place compute close to users. Dassault Systèmes, led by Bernard Charlès, evolved 3DEXPERIENCE to support private and hosted deployments for regulated industries, where air-gapped or edge-aligned clusters satisfy sovereignty, determinism, and on-prem latency requirements without sacrificing collaboration features.

Autodesk, under Andrew Anagnost, expanded Fusion and Autodesk Platform Services as a backbone for design-to-make workflows. Partners commonly pair Autodesk’s cloud with NICE DCV or PCoIP/HP Anyware at the edge for high-fidelity sessions, especially where RTX-class rendering or sensitive IP constraints rule out thick client installs. Siemens, while historically strong with NX and Teamcenter in on-prem modes, has embraced hybrid cloud and metro-proximate deployments to enable cross-site reviews with lower latency. The pattern across vendors is convergent: keep kernels authoritative and services orchestrated centrally, but place session-critical compute nearby. Enterprises are complementing this with SASE/zero-trust access, carving secure paths from factory floors, job sites, and service vans to regional edges where collaborative CAD and visualization feel local and compliant.

Omniverse and scene-centric workflows

NVIDIA, with Jensen Huang at the helm, has pushed the industry toward scene-centric collaboration via Omniverse. By embracing USD as the unifying scene description, Omniverse’s Nucleus servers coordinate live edits, instancing, materials, and variants across multiple DCC, CAD, and simulation tools. Connectors bridge Siemens, Autodesk, and Dassault ecosystems, so that a change in a CAD model can propagate into visualization, simulation, and even robotics contexts. Running Nucleus and RTX-powered Omniverse Kit apps at the edge is a natural fit: review participants across sites experience USD-based live sync with predictable responsiveness, and the heavy lifting—path tracing, MDL material evaluation, and AI denoising—occurs near users.

Beyond reviews, scene-centric approaches power digital twins, combining CAD with point clouds, sensor data, and procedural environments. On the factory side, DELMIA’s process simulations and Siemens’ manufacturing datasets flow into Omniverse for ergonomic, collision, and throughput analyses. For robotics and autonomous systems, Isaac Sim and related Omniverse components use RTX to render sensor-accurate scenarios. Edge-hosted Nucleus aligns with these tasks by ensuring that local teams can iterate rapidly while maintaining USD’s composition guarantees globally. The upshot is a shift from file interchange to context interchange: instead of exporting and reimporting, teams change state in a shared scene and watch other tools reflect that state in near real time, wherever the work is happening.

Protocols and ecosystem components

Under the hood, streams and formats do the heavy lifting. On the transport side, NVENC’s AV1 encoder has gained traction for quality-per-bit, critical where metro networks are good but not perfect. For low-latency delivery on lossy paths, SRT and WebRTC are workhorses; the latter benefits from QUIC’s congestion control and connection migration for mobile devices. NICE DCV remains a favorite for high-fidelity workstation remoting, while PCoIP/HP Anyware and Citrix HDX/EDT serve enterprises with mature virtualization estates. On the visualization and interchange front, OpenUSD orchestrates scene graphs across tools; glTF provides a compact runtime for web and mobile; and 3D Tiles serves geospatial-scale assets in construction and infrastructure reviews, as adopted in Bentley iTwin and the Cesium ecosystem.

- Geometry compression: Draco for mesh deltas, BasisU for textures when streaming client-side rendering payloads.

- CAD interchange: STEP AP242 for MBD fidelity; JT and PLMXML persist in Teamcenter-driven flows; USDZ packages USD for mobile.

- Composition: USD’s references, variants, and payloads minimize duplication and enable multi-level LOD authoring.

- Transport trade-offs: WebRTC for browser reach and sub-200 ms latencies; SRT for resilient links; DCV/PCoIP for workstation semantics.

The ecosystem’s direction is pragmatic: use OpenUSD for shared context, glTF and 3D Tiles where runtime constraints dominate, and pair encoding/transport to the session’s shape. Edge simply makes these choices more forgiving. Shorter RTTs permit smaller jitter buffers; proximity reduces packet loss; and adaptive bitrate controllers settle faster. The protocol stew is no longer a liability when the network path is metropolitan, predictable, and engineered with the workload in mind.

Security and IP protection at the edge

Protecting CAD IP is non-negotiable. Edge architectures lean on remote rendering so that raw B‑reps and parametric histories never leave servers. Zero-trust access patterns—identity-aware proxies, mTLS between services, and per-session authorization—tighten exposure. Media streams travel via SRTP with short-lived keys, while control channels use mTLS and strong OIDC/OAuth tokens. For sensitive programs, confidential computing technologies such as AMD SEV‑SNP and Intel TDX allow GPU-adjacent VMs to run with memory encryption and remote attestation, providing cryptographic proof that kernels and renderers execute in trusted enclaves.

- Watermarking: per-session, per-user overlays and forensic watermarking deter leaks and aid attribution.

- Audit trails: edge nodes emit signed logs that integrate with PLM systems like Teamcenter, Windchill, and 3DEXPERIENCE for compliance.

- DLP and egress control: clipboard/USB restrictions, screenshot detection signals, and policy-driven data paths.

- Key hygiene: ephemeral secrets, HSM-backed root keys, and attested boot for edge clusters.

Security extends to operations. Image supply chains are signed; SBOMs are verified; and admission controllers prevent drift. Network microsegmentation confines blast radius. Even in hybrid render modes that stream geometry to clients, payloads can be reduced to tessellations without PMI or feature history, keeping sensitive intent server-side. In effect, edge can be more secure than traditional desktops: there is less “stuff” to steal on endpoints, and what flows is monitored and revocable. The trust model becomes modern: assume breach, verify continuously, and keep the crown jewels central—only the minimum required representation crosses the wire.

Real-time CAD that feels local

Edge closes the latency gap

The promise of “Google Docs for CAD” languished for years against the hard wall of latency. Edge computing scales that wall. By placing modeling kernels and GPUs near users—in Wavelength/Local Zones, Azure Edge Zones, and telco MEC sites—round-trip times drop, jitter flattens, and the subtle timing of constraint manipulation starts to feel native. Large assemblies no longer elicit dread during reviews; parameter scrubs respond fluidly; and streamed RTX visuals hold cadence. The effect is pronounced in AR/VR, where motion-to-photon budgets are ruthless. With edge proximity, OpenXR clients can rely on late-latching and timewarp to hide rendering variance while the network ceases to be the dominant source of lag.

Practically, this reframes where work happens. Construction coordination at job sites, factory commissioning on the plant floor, and field service overlays benefit when compute is local in spirit, cloud in scale. Teams distributed across continents hold multi-site design reviews that no longer feel transoceanic, because they aren’t—at least not in the critical path. The central region orchestrates, archives, and secures; the edge converses in real time. As carriers densify 5G and fiber backhaul, and as vendors harden edge orchestration, the difference between “on-prem” responsiveness and “cloud” convenience narrows to the point of irrelevance. The upshot is cultural as much as technical: exploration becomes cheap again, and the tools get out of the way.

The winning stack and what’s next

Winning stacks share a pattern: standardize on scene graphs that compose well, stream just enough geometry, render where it makes sense, and merge edits without locks. USD/OpenUSD underpins shared context with composition arcs and variants; progressive geometry streaming (Draco-compressed tessellation deltas, USDC payloads) keeps bandwidth lean. Edge GPUs deliver RTX-class remote rendering when fidelity or IP concerns demand it, while WebGPU/WebGL clients handle local draw with foveated/variable-rate shading to stretch device budgets. Edits flow as operation streams; CRDT/OT-inspired strategies make merge order a detail, not a disaster; constraint solving happens near users, with global reconciliation wrapping up in the background. The transports are low-latency and modern—WebRTC/AV1, DCV, or PCoIP—wrapped in a zero-trust envelope and, where needed, guarded by confidential computing.

- USD/OpenUSD scene graphs and progressive streaming for shared, efficient context.

- Edge GPUs for remote rendering, plus WebGPU clients for hybrid draw.

- CRDT/OT-style concurrency with near-user constraint solving.

- Low-latency transports (WebRTC/AV1, DCV, PCoIP) with SRTP and mTLS.

Expect rapid growth where distance and determinism matter most: multi-site design reviews, on-site construction coordination, factory commissioning, and field service AR. As ecosystems around NVIDIA Omniverse, Autodesk Platform Services, PTC Atlas, and Dassault 3DEXPERIENCE continue to integrate with edge-native orchestration, the experience will cross a threshold: real-time CAD collaboration will feel local—even when teams are continents apart. The industry won’t abandon central clouds; it will complement them with a fabric of nearby, purpose-built compute that treats latency as a first-class design constraint. That’s the future: an edge that respects the way designers think and move, and a cloud that scales their intent without slowing their hands.

Also in Design News

Live Performance Budgets: Real-Time Cost, Carbon, Energy and Lead-Time in CAD/BIM

December 11, 2025 14 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Cinema 4D Soft Body Quick Setup & Parameter Tuning

December 11, 2025 2 min read

Read More

AutoCAD Tip: Annotate and Plot from Paper Space for Consistent Sheets

December 11, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …