Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History: Why B-rep Was Invented: From Wireframe and CSG to Kernels, Topology, and Robust Solid Modeling

January 22, 2026 13 min read

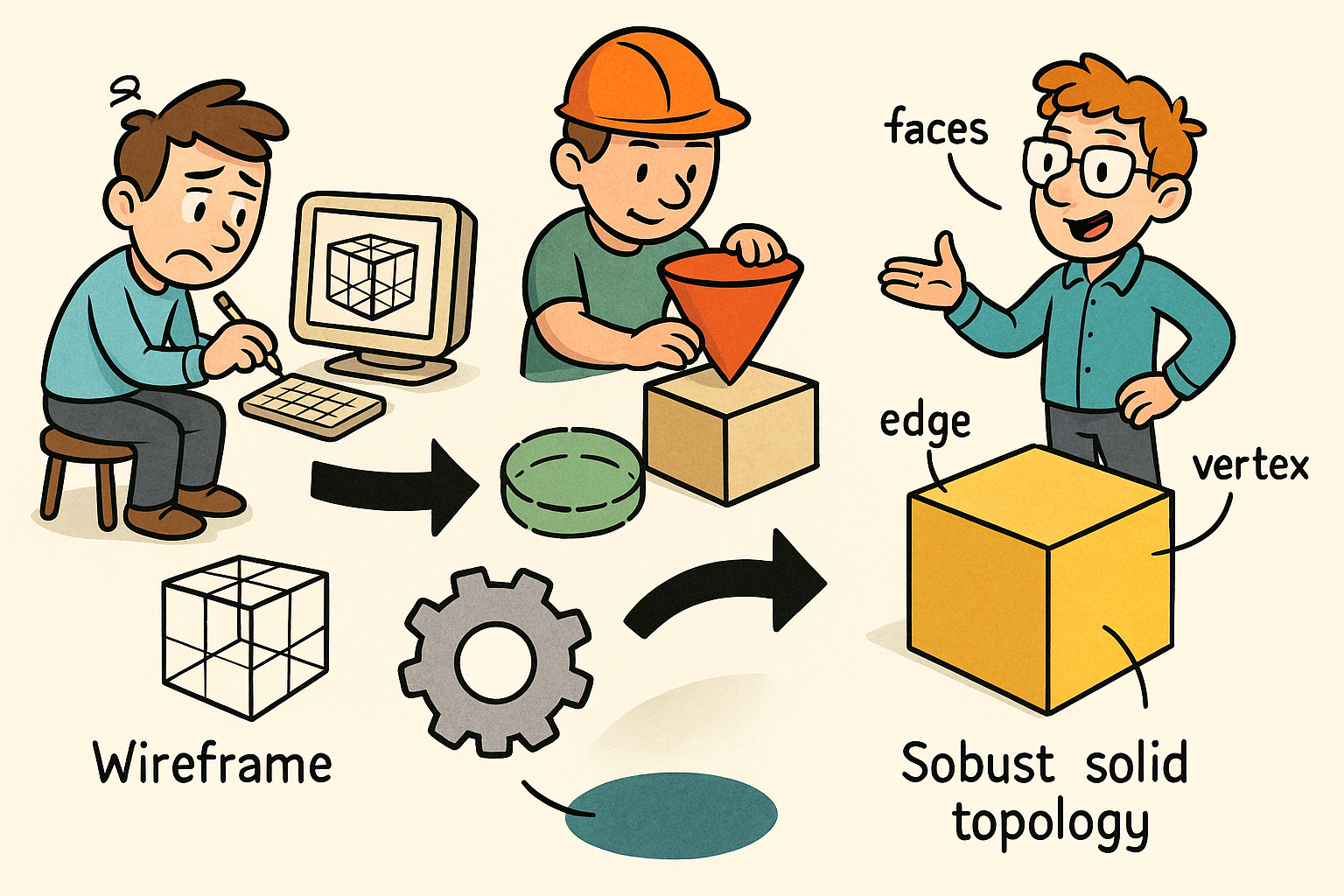

Why B-rep Had to Be Invented: From Wireframe and CSG to Solid Topology

Limitations that set the stage

By the early 1970s, the inability of wireframe and early constructive solid geometry (CSG) models to encode what constitutes a “solid” drove the search for a richer representation. Wireframe systems—descendants of Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad lineage—could display vertices and edges but carried no explicit notion of interior versus exterior. This meant hidden-line removal was a heuristic, view-dependent decision rather than a property of the model; a slight numerical perturbation or coincident edge could toggle visibility and create contradictory results across different projections. Worse, wireframes could represent impossible figures: open edges, non-planar loops, and self-intersections that had no physical realization. CSG, introduced as Boolean compositions of geometric primitives, added logical clarity, yet traded editability for declarative construction trees. While CSG’s set operations were robust for primitives, it faltered under the demands of local shape editing, especially where product designers needed subtle fillets, draft angles, and freeform blends that were not easily expressible as primitive combinations.

What industry demanded was a model that made “solidness” explicit and analyzable while remaining editable at the local level. That pressure came from disparate quarters—automotive and aerospace surface design, mechanical detailing, and tooling—each needing both interactive modeling and downstream computation. The gaps were stark:

- Wireframe ambiguity: no encoded inside/outside; fragile hidden-line logic; inability to guarantee watertightness or manifoldness.

- Early CSG strengths and weaknesses: rigorous Boolean algebra on simple primitives, but poor locality of control and difficulty expressing fillets, drafts, and freeform transitions.

- Analysis and manufacturing needs: mass properties, sectioning, offsetting, and machining paths all require a watertight boundary or volume definition, not a network of unqualified edges.

These failures framed a clear research question for the decade: how to define solids rigorously, maintain topology under edits, and separate the numerical geometry from the combinatorial adjacency that gives models their continuity and legality. That question set the stage for boundary representation—better known as B-rep—to emerge as the synthesis of mathematical regularity and editable structure.

Theoretical foundations of “solids”

The theoretical response began with the nature of solids as sets. At the University of Rochester, A.A.G. (Ari) Requicha and Herbert B. Voelcker articulated the concept of r-sets (regular sets) and regularized Boolean operations—closure operations that ensure unions, intersections, and differences of solids remain solids by eliminating dangling, lower-dimensional detritus along boundaries. Their work transformed the informal idea of a 3D part into a mathematically disciplined object: the interior, boundary, and exterior of a solid had to obey topological rules, and Boolean operations had to return objects in the same category. This rigor proved decisive for CAD, where geometric operations must be reliable for downstream analysis and manufacturing.

Hand-in-hand with regularization came the Euler–Poincaré framework that constrains topology. For orientable, manifold solids, relations linking vertices, edges, faces, shells, and connected components (with genus accounting for holes) act as invariants that an editing system must preserve to keep a model valid. In practical CAD terms, these invariants serve as sanity checks: no operation should silently create an edge with one incident face, a face with a non-closing loop, or a shell whose orientation contradicts its neighbors. Later, as models incorporated multiple shells (e.g., voids), these relationships were extended to reflect the algebra of genus and components. Concepts that today feel standard—inner loops representing holes, consistent face orientation, and shell normals that point outward—descend directly from this foundational period.

Two separations followed from this theory and remain essential. First, geometry versus topology: planes, cylinders, cones, spheres, and later NURBS patches define embedding surfaces; topology defines the “glue”—edges, loops, and faces—that trims and orients these surfaces into a closed boundary. Second, validity versus edit operations: so-called Euler operators were defined to add or remove topological elements while preserving the invariants. Those ideas, which Jaakko Mäntylä would later codify, supplied the systematized toolkit that turned abstract theorems into reliable editing sequences inside modelers.

Pioneering data structures

Making these ideas computable required the right data structures. At the Stanford AI Lab (1972–1975), Bruce Baumgart introduced the winged-edge structure, the first systematic, pointer-rich encoding that tied each edge to its two incident faces and four surrounding vertices, enabling traversal around a face boundary and across adjacent faces. Although memory hungry by the standards of the day, winged-edge demonstrated that adjacency was a first-class citizen, not a side-effect of geometry. That insight, more than any particular pointer scheme, changed the trajectory of CAD by disenfranchising purely geometric proximity and elevating explicit topological neighborhood.

A decade later, Leonidas Guibas and Jorge Stolfi presented the directed, or doubly connected edge list—better known as the half-edge (DCEL)—providing a cleaner, orientation-aware approach where each edge is split into two oppositely directed half-edges. This allowed unambiguous traversal of loops, a consistent definition of face orientation, and a modular separation of geometric data (points, curves, surfaces) from topological structure (vertices, half-edges, faces). DCEL and its variants became the blueprint for many industrial B-rep kernels. Completing the toolset, Jaakko Mäntylä synthesized practice and theory by formalizing Euler operators—like make-edge-vertex and kill-face-edge—that guarantee validity if applied with the right preconditions, ultimately captured in his 1988 book “An Introduction to Solid Modeling.”

This fusion of data structures and operators made “solids as topology on geometry” a practical reality. Traversals for Boolean classification, face splitting, and loop creation became algorithmically well-posed. As the field matured, developers discovered that these structures also facilitated diagnostics—checking manifoldness, detecting dangling entities, and validating orientation—thereby weaving correctness checks into the bones of the modeler. Without winged-edge, half-edge, and the discipline of Euler operators, B-rep would have remained a theoretical curiosity rather than the backbone of modern mechanical CAD.

The Birth of B-rep in Practice: Cambridge, BUILD/MODEL, and Shape Data’s ROMULUS

Cambridge University CAD Group (early–mid 1970s)

Turning theory into a working modeler happened in earnest at the University of Cambridge. Under Ian C. Braid, with colleagues including Alan Grayer and Charles Lang, the CAD Group built prototype systems—most notably BUILD and MODEL—that encoded solids with explicit faces, loops, and shells, and enforced topological validity during edits. Their central move was to separate the immutable geometry of surfaces (planes, cylinders, tori, and eventually freeform patches) from the mutable topology that trims and joins those surfaces into a closed boundary. Every operation that altered the model did so as a sequence of validity-preserving topological edits augmented by geometric calculations such as intersections and projections.

What seems obvious now—that a face is a trimmed piece of a surface, with one outer loop and zero or more inner loops representing holes—was profound then. The Cambridge systems ensured consistent orientation for loops and faces, required that edges be shared by exactly two faces in a manifold body, and computed classifications during operations to prevent illegal constructs. Out of these rules came practical editing capabilities. Designers could cut a slot by splitting faces and adding loops; they could form a pocket by removing a face while preserving the shell’s manifoldness; they could adjust fillet radii by modifying curves while the surrounding topology kept the model watertight. The careful enforcement of invariants meant that downstream operations like mass property computation, sectioning, and eventually toolpath generation could be trusted.

Equally important, these prototypes experimented with the data interchange between numeric routines and topological edits. For example, face–face intersections produced intersection curves that were parametrically trimmed and then incorporated into the topological graph. Errors and tolerances were not swept under the rug; they were recognized as inherent in floating-point computation, leading to early notions of toleranced coincidence and geometric “snap” rules used to keep edges meeting and loops closing. In BUILD and MODEL, one sees the genesis of industrial B-rep practice: a dance between precise geometric computation and formally constrained topological surgery.

From lab to industry

Academic prototypes are necessary, but industry requires durability, performance, and supported distribution. To bridge that gap, Braid, Grayer, and Lang founded Shape Data Ltd, carrying the Cambridge approach into a commercially viable kernel. The result was ROMULUS (1979), followed by ROMULUS A in the early 1980s, among the first commercial B-rep kernels that vendors could license and embed. This was more than software; it was a new business model that treated the solid modeling core as a reusable component—what would later be called the “kernel inside” model. Independent CAD systems could differentiate on UI, drafting, and application features while relying on a common, rigorously engineered B-rep heart.

ROMULUS established patterns that define kernels to this day. Its API exposed operations in terms of faces, edges, and loops, and encoded the guarantees around validity, orientation, and adjacency. It supported analytic surfaces, robust face splitting, and Boolean operations cast as topology-preserving edits guided by geometric intersection classification. Crucially, it dealt with the ambiguity of numeric computation by managing tolerances and providing normalization steps after heavy surgery. As the kernel matured, early licensees in Europe, the UK, and the US validated that a common solid core could power diverse applications, from mechanical design to tooling.

The migration from Cambridge’s lab to Shape Data’s product also clarified organizational roles in CAD. Kernel engineers focused on numerics, topology, and geometric algorithms. Application developers built feature modeling, parametric sketchers, and industry-specific workflows atop that platform. Sales and OEM relationships created a supply chain where advances in the kernel could ripple across many products. This architecture—conceived in the ROMULUS era—made possible the later rise of Parasolid, ACIS, and open-source stacks, and it transformed CAD from monolithic codebases into a layered ecosystem with well-defined responsibilities and lifecycles.

Early algorithmic breakthroughs

ROMULUS and its contemporaries crystallized the key algorithms that still define B-rep robustness. Boolean operations were implemented not as crude union/intersection of point clouds or meshes but as face–face intersection pipelines followed by classification and topology-preserving splitting and merging. Each intersection produced candidate curves that had to be trimmed, oriented, and sewn back into the surrounding faces. The kernel then determined which side of the cut belonged to which operand, a classification problem complicated by numerical noise and nearly coincident geometry. Getting this right was the difference between a valid, watertight solid and a leaky assembly of surfaces.

Another breakthrough was the treatment of trimming as a first-class construct. Rather than requiring surfaces to be bounded by their natural parameterization, the kernels allowed arbitrary loops to carve out usable regions, enabling complex holes and islands on faces. This idea unlocked modeling workflows: a pocket became a loop on a face; a slot became a pair of loops connected by split edges; a cutout became a loop that could be toggled between add/remove semantics under Booleans. Around these operations grew techniques that would later be called healing—strategies to reconcile small gaps, sliver faces, and near-degenerate edges that appear after ill-conditioned intersections or cumulative edits.

Developers learned to rely on a suite of checks and fixes after each operation:

- Classification of new faces and edges relative to operand interiors.

- Sewing to ensure loops close and edges are shared by the correct number of faces.

- Normalization to merge nearly coincident vertices and align edge parameterizations.

- Validity audits using Euler–Poincaré constraints.

These early choices injected a culture of robust numerics and explicit topology into the kernel DNA. They also foreshadowed later concerns—like tolerance management and exact predicates—that would shape the next generation of solid modeling engines.

Industrialization and Evolution: Kernels, NURBS, Robustness, and Hybrids

The kernel era

By the late 1980s and 1990s, CAD matured into a “kernel era” with multiple competing, high-performance B-rep cores. Parasolid, originating at Shape Data and later shepherded under Unigraphics and then Siemens Digital Industries Software, grew into the dominant commercial kernel, powering products such as Siemens NX, SolidWorks (for many releases), and later cloud-native systems like Onshape. In parallel, ACIS emerged from Spatial Technology, founded by Dick Sowar around 1986–1989, and was later acquired by Dassault Systèmes; Autodesk’s ShapeManager is a fork derived from ACIS, illustrating how kernel technology becomes a platform for vendor-specific evolution.

The ecosystem diversified further with Open CASCADE Technology, originating from Matra Datavision’s CAS.CADE and open-sourced in 1999, becoming the backbone of FreeCAD, SALOME, and a broad swath of research and industrial tools. Meanwhile, other proprietary cores—CGM (Dassault Systèmes) and Granite (PTC)—reinforced the “kernel inside” pattern across major suites. This segmentation allowed vendors to innovate in parametrics, assemblies, and domain-specific applications while relying on hardened B-rep fundamentals for geometry.

Beyond commercial positioning, this period standardized the kernel playbook:

- API stability and binary compatibility to support long-lived OEM integrations.

- Performance engineering for Booleans, offsetting, and patterning across large models.

- Scalable tolerancing frameworks to survive the realities of floating-point computation and industrial units.

- Extensible geometry libraries supporting analytic and freeform surfaces, with common evaluation contracts.

As kernels industrialized, their success nourished an application layer that could assume solid reliability in the core while pushing the envelope in feature-based modeling, constraint solving, and collaboration. The separation of concerns that began at Cambridge matured into a robust industry architecture.

Geometry gets real: NURBS and trimmed surfaces

While early B-rep relied on analytic surfaces, the demand for smooth, automotive-quality shapes required a leap. In the 1970s, Ken Versprille’s doctoral work crystallized NURBS (Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines), providing an exact, compact representation for conics and freeform curves and surfaces, with local control and continuity management. For B-rep, NURBS solved a core problem: how to represent aesthetically controlled yet precisely defined shapes that could be trimmed, joined, and manufactured. Kernels rapidly adopted NURBS evaluation, differentiation, and knot insertion/removal as standard operations, and extended the B-rep trimming concepts to parametric NURBS domains.

With NURBS came the computational heavyweights: surface–surface intersection, robust trimming, and gap/overlap management. Intersections between two NURBS surfaces yield curves that rarely have closed forms; kernels deploy iterative methods (e.g., marching and Newton refinement) alongside interval strategies to converge to accurate solutions. These curves then must be represented consistently in both surface parameter spaces, oriented properly, and reconciled with existing topology. The result is a cycle: intersect, classify, trim, sew, and heal. This cycle is the heartbeat of modern B-rep Booleans and local edits.

Practical kernels layered several techniques to make this dependable:

- Dual-parametric representations of intersection curves to reduce drift between surface parameterizations.

- Adaptive tolerances that respect model units and scale, balancing over- and under-merging risks.

- Knot-space operations (reparameterization, degree elevation) to align continuity across joins.

- Discontinuity-aware meshing that recognizes kinks (C0) and maintains faithful tessellation for visualization and downstream analysis.

These capabilities transformed B-rep from a topological container for simple geometry into a vehicle for high-end styling and engineering, enabling everything from turbine blades to consumer electronics casings to be modeled with both aesthetic and manufacturing rigor.

Topology expands and toughens

Most early B-rep assumed manifold solids—every edge incident to exactly two faces and every vertex embedded in a single, well-behaved neighborhood. However, real-world workflows exposed the need for more general adjacency. In the mid-1980s, Kevin Weiler introduced the radial-edge data structure, extending the winged/half-edge family to support multiple faces meeting around an edge. This unlocked non-manifold constructs, sheet bodies, and mixed-dimensional models—vital for mid-surface extraction, shell modeling, and certain analysis workflows. Modern kernels commonly maintain manifold bodies as the default but allow non-manifold topologies to exist in a controlled fashion for specific operations and representations.

As topology broadened, validation and repair hardened. Kernels implemented Euler checks across shells and components, enforced consistent face normals and loop orientations, and created systematic sewing routines to convert surface quilts into watertight bodies. Libraries for small-face and sliver removal emerged to tame the artifacts of aggressive feature operations and imported data. To counter the fundamental fragility of floating-point arithmetic, vendors built tolerance frameworks that track model-space and parametric-space discrepancies, often coupling them with snap-to rules and geometric filtering to prevent runaway error accumulation.

Numerical robustness deepened as developers incorporated exact predicates in sensitive algorithms (e.g., orientation tests) and used interval arithmetic or certified marching in intersection pipelines. The goal was not to make everything exact—industrial CAD must remain performant—but to quarantine uncertainty where it does the least harm and to make the system’s inferences explicit. The result is a more predictable, self-healing modeler that can digest pathological inputs, handle near-degenerate edits, and still produce analyzable, manufacturable solids.

Beyond “pure B-rep”: practical hybrids

Even as B-rep matured, practitioners learned that no single representation suffices. Kernels embraced CSG+B-rep hybrids by executing Booleans via B-rep operations while preserving high-level feature semantics for design intent. Feature history layered on B-rep enabled parametric modeling but introduced the infamous persistent naming problem, where faces and edges acquire unstable identities under topological change. Vendors devised heuristics and graph-based schemes to track identity across edits, but the problem remains a frontier, especially under large, localized modifications.

At the same time, direct editing arose as a complement to history-based workflows, offering push–pull operations, face offsets, and local constraint solves that modify the B-rep without replaying the entire feature tree. Kernels added specialized operations—offset, replace-face, move-face, and surface extension—to support these elastic edits. Interoperability matured in parallel: from IGES to STEP AP203/AP214/AP242, B-rep exchange gained fidelity, while semantic PMI and Model-Based Definition (MBD) demanded stable topology and precise geometric references to carry tolerances, GD&T, and manufacturing intent across tools.

Modern pipelines increasingly mix representations: polygonal meshes for visualization and simulation, implicit fields for lattice and generative forms, and B-rep for precise boundaries and manufactured surfaces. Successful systems treat B-rep as the authoritative carrier of exact geometry and topology, while maintaining bridges to meshes and implicits for speed, scale, and creativity. The most effective hybrid strategies rely on careful conversion contracts, toleranced snapping, and verification loops that ensure what returns to B-rep remains watertight, valid, and semantically faithful to the designer’s intent.

Conclusion

What B-rep solved

Boundary representation solved the core deficiencies of its predecessors by encoding solids as oriented, watertight boundaries with explicit topology on top of precise geometry. Where wireframes equivocated about visibility and interiority, B-rep made inside/outside and adjacency central. Where early CSG raised the bar for Boolean correctness but limited local control, B-rep embedded local editability into the model itself—faces, edges, and loops that can be split, merged, trimmed, and healed while invariants guarantee continued validity. This, in turn, unlocked dependable downstream computation—mass properties, sectioning, offsetting, and manufacturability—without requiring ad hoc fixes at every stage.

From Bruce Baumgart’s winged-edge to Guibas–Stolfi’s half-edge and Weiler’s radial-edge, the data structures matured to carry increasingly complex adjacency. From Requicha and Voelcker’s regularized operations and Euler–Poincaré constraints to Jaakko Mäntylä’s Euler operators, the mathematics of solids became actionable code paths. And from Cambridge’s BUILD and MODEL to Shape Data’s ROMULUS, those ideas cohered into a practical kernel blueprint. The industrialization that followed—Parasolid, ACIS, Open CASCADE Technology, along with CGM and Granite—proved that the kernel-as-component model could scale across vendors, industries, and decades. B-rep answered the fundamental question of how to represent, edit, and analyze solids with rigor, providing a stable platform on which CAD’s higher-level innovations could thrive.

As a concise summary of impact:

- Editable precision: topology-preserving edits on exact geometry produce robust, analyzable parts.

- Algorithmic discipline: intersection, classification, trimming, and sewing form a coherent, repeatable pipeline.

- Ecosystem scalability: kernels as components enable broad innovation above a dependable core.

Enduring legacy and next frontiers

Today’s workflows rely on B-rep at the core, augmented by hybrids that reflect practical needs. Feature histories and direct edits coexist; Booleans lean on B-rep intersections; meshes accelerate visualization and simulation; implicits power generative and lattice structures. Interoperability through STEP AP242 carries not just geometry but also PMI and semantic tolerances, forcing kernels to preserve identity and intent across translations. Meanwhile, the hardest problems remain active research and development topics. The persistent naming problem continues to challenge parametric robustness. Robustness demands continue to push toward exact arithmetic at scale for selective predicates and certified computations, balanced against performance and memory realities. And hybrid modeling raises new questions about seamless conversions—how to round-trip between implicits, meshes, and B-rep without losing design semantics or introducing topological noise.

Crucially, these are extensions rather than replacements. Just as NURBS extended B-rep into freeform territories and radial-edge generalized adjacency without discarding manifold discipline, the next wave will expand B-rep’s reach. We can expect tighter error accounting, more resilient topological identity, and smarter bridges across representations. The arc that began with Cambridge’s careful separation of geometry from topology and was industrialized by ROMULUS, Parasolid, ACIS, and Open CASCADE will continue to define the professionalization of CAD’s core. In that sense, the story of solid modeling is not one of disruptive turnover but of cumulative refinement—a steady strengthening of rigorous topology, robust numerics, and scalable kernels that keeps boundary representation at the center of how engineers and designers think about, edit, and exchange the shapes that become real-world products.

Also in Design News

Tamper-Evident Design Histories: Cryptographic Provenance, Append-Only Logs, and Deterministic Rebuilds

January 22, 2026 11 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: MatCap Shading for Rapid Form and Topology Feedback

January 22, 2026 2 min read

Read More

V-Ray Tip: Stylized Colored Rim Lights for Physically Plausible Silhouette Readability

January 22, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …