Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

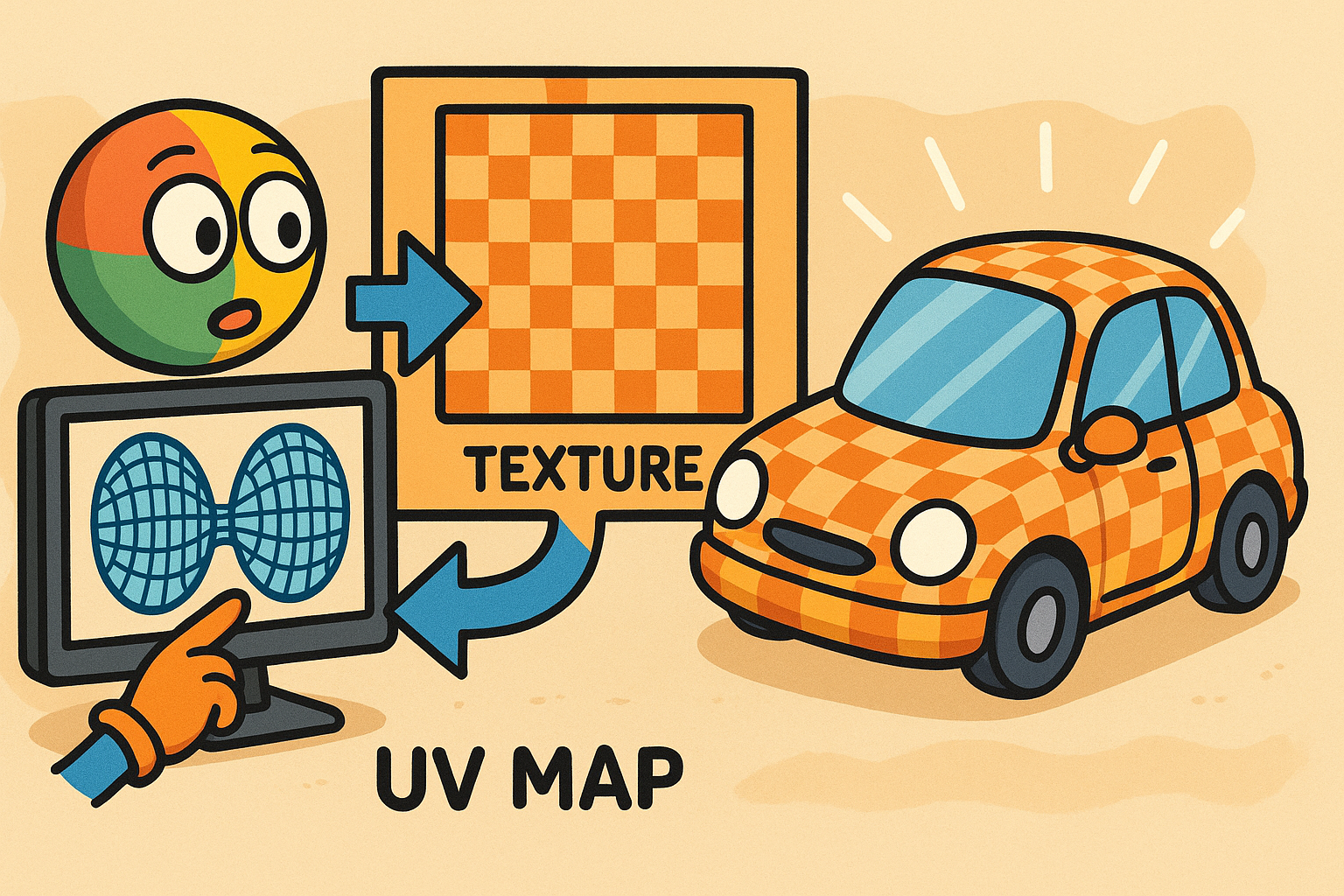

Design Software History: UV Mapping and Texture Pipelines: From Parameter Spaces to Product Visualization

December 15, 2025 11 min read

Origins: from parameter spaces to pixels

Early ideas that unlocked texturing

Computer graphics’ march from wireframes to photorealistic imagery hinged on one deceptively simple concept: mapping pictures onto shapes. In the mid‑1970s, Ed Catmull articulated the crucial bridge by formalizing per‑surface (u,v) parameterization, a way to think about each point on a surface as a coordinate in a tidy, two‑dimensional domain. That abstraction meant a bitmap—indexed by two numbers—could be attached not to a screen rectangle, but to a curved patch. Catmull’s insight gave researchers a common language for sampling, filtering, and addressing texture data on arbitrary surfaces, whether spline patches or triangulated meshes.

Jim Blinn amplified the magic with pioneering illusions of micro‑structure that did not exist in geometry. His bump mapping (via perturbing normals) transformed flat surfaces into convincing relief, and his environment mapping redirected reflections without ray tracing a complex world. Both techniques depended on stable parameterization and consistent sampling to avoid shimmering and distortion. Lance Williams completed this early trifecta by introducing mipmapping, a pyramidal set of prefiltered texture levels that drastically reduced aliasing and improved cache locality. Mipmapping reconciled the unhappy marriage between discrete pixels and continuous surfaces by selecting the right resolution for the projected footprint of a texel. Together, these contributions made texturing practical, predictable, and performant on the limited hardware of the day, setting the stage for professional tools to treat image mapping as a first‑class modeling operation rather than a post‑process gimmick. They also cemented the habit of reasoning about textures in parameter space, an intellectual foundation that would echo across CAD, DCC, and visualization for decades.

Why “UV” stuck in CAD and DCC

Long before polygonal modeling dominated entertainment tools, engineering systems represented objects as smooth, analytic surfaces. NURBS—and their B‑spline cousins—came with a built‑in two‑dimensional domain, universally written as (u,v). When polygonal UV mapping matured in digital content creation software, practitioners already spoke the NURBS dialect, and the “UV” shorthand transferred cleanly to triangles and quads. In essence, the term migrated from mathematics to production vernacular: a practical handle for the notion that a point on a surface equals a point in a 2D parameter chart. CAD users were accustomed to trimming curves, evaluating isoparms, and reasoning about surface continuity; texture coordinatization felt like a natural extension rather than a foreign procedure.

Early product visualization exploited this cultural overlap. Industrial design teams began piggybacking on the rapid advances in DCC, adopting texture workflows from Alias|Wavefront, Softimage, and LightWave to paint prototypes, add decals, and simulate finishes well before physical samples existed. Terminology and practices like “seams,” “relax,” and “pinning” migrated into design studios alongside terms such as zebra stripes and curvature combs. Because CAD surfaces already had meaningfully parameterized domains, their export into polygonal tessellations retained enough structure to make “UVs” feel native. This alignment is why “UV” endures as the catch‑all label across two historically distinct worlds. It bridged the gap between engineering rigor (where parameter spaces are mathematically defined) and creative workflows (where parameter spaces are practical canvases), enabling consistent texture placement, repeatable material definition, and the eventual convergence of rendering pipelines for entertainment and industry.

Early industrial visualization stack

By the 1990s, visualization for automotive and aerospace matured into an ecosystem with textured surfaces at its core. Alias Studio and AutoStudio, widely used in transportation design, provided designers with precise surfacing and visualization tools, while CATIA’s visualization modules gave aerospace teams pathways to review assemblies with realistic materials. Texture support in these environments leaned on plug‑ins and external renderers that made charts and images behave in review sessions and printed media. Render engines such as Mental Ray (from mental images), Pixar’s RenderMan, and later early V‑Ray builds from Chaos provided filtering, antialiasing, and shading models that respected parameterization and projection.

This stack made textures practical in enterprise settings because it covered both authoring and presentation. Designers could assign decals and labels via cylindrical or planar projections, leverage texture space for stitch lines or graining, and present results to stakeholders under matched lighting. Pipelines often looked like this:

- Surface definition in Alias Studio/AutoStudio or CAD tools, retaining native parameter spaces.

- Tessellation into polygons with UVs carried or regenerated for visualization robustness.

- Rendering through Mental Ray, RenderMan, or V‑Ray with mipmapping and anisotropic filtering.

- Output to print, slide decks, and early web content for marketing and internal reviews.

Even on modest hardware, the combination of parameterized surfaces, UV‑aware tessellation, and mipmapped textures meant designers could preview paint breaks, badges, instrument clusters, and seat textiles credibly. The effect was transformative: texturing stopped being an exotic post‑pipeline step and became part of everyday CMF review, enabling faster iteration cycles and richer communication between industrial designers, engineers, and marketers.

Unwrapping the 1990s–2000s: tools, algorithms, and workflows

Core algorithms that made UVs viable at scale

As assets grew in complexity, the manual art of cutting seams and pushing points needed mathematical muscle. Two algorithms became foundational: Least Squares Conformal Maps (LSCM) and Angle Based Flattening (ABF/ABF++). LSCM, attributed to Bruno Lévy and collaborators, sought to minimize angular distortion by solving a least‑squares system that preserves local angles when mapping from 3D to 2D. ABF and its improved variant ABF++, advanced by Alla Sheffer and colleagues, approached the same problem from the angle space, optimizing the target triangle angles directly under constraints that ensure a valid, invertible map. Both techniques dramatically reduced shearing and stretching, especially on organic or smoothly curved surfaces, and became the backbone of “relax” operations in UV editors.

Quality needed measurement, not intuition. Works by Sander et al. popularized stretch/area metrics that visualize how texels deform, while ubiquitous checkerboard overlays provided immediate feedback to artists and engineers. These diagnostics encouraged early separation of shells in areas with high curvature, better seam placement down low‑visibility regions, and more uniform texel density. Packing unfolded shells into a texture atlas rode on bin‑packing heuristics that balanced rotation, scaling, and adjacency—vital for squeezing quality out of limited texture budgets. Over time, packers added features such as grouping, padding for mip leaks, and multi‑tile exports, laying the groundwork for tile conventions like UDIM. Together, conformal unwrapping, robust metrics, and smarter packing upgraded UVs from artisanal craft to systematic practice capable of handling massive models without collapsing under distortion or waste.

The rise of UV editors and 3D painters

Algorithmic advances landed in users’ hands via the dedicated UV editors that became standard in DCC suites. Alias/Wavefront’s Maya UV Editor established familiar interactions—marking seams, pinning vertices, relaxing charts, and layout automation. 3ds Max’s Unwrap UVW (Kinetix/Discreet, later Autodesk) gave game artists and visualization specialists fine‑grained control over shells and texel density. Softimage and LightWave brought their own editors to production, while Modo and Blender later broadened access with elegant tools and scripting hooks. In these interfaces, artists could think simultaneously about geometry and fabric: where to hide seams, how to align anisotropy to flow lines, and how to keep logos undistorted on rounded corners. These editors normalized vocabulary and made the invisible visible, foregrounding sampling, filtering, and distortion as everyday concerns.

Alongside, 3D painting bridged the 2D artist’s sensibilities with 3D assets. Maxon’s BodyPaint 3D and Right Hemisphere’s Deep Paint 3D allowed direct paint strokes onto models, writing into UV‑mapped textures with live feedback. Even Adobe Photoshop added 3D painting features, letting illustrators leverage familiar brush engines on mapped surfaces. The combination transformed workflows:

- Seams were planned early for minimal art interruptions.

- Procedural textures were combined with hand‑painted passes for realism.

- Decal layers carried labels and badges without disturbing base materials.

- Baking pipelines moved normals, ambient occlusion, and curvature from high‑poly to UV texture space.

The result was a feedback loop: better unwrapping encouraged more ambitious painting, and better painting demanded cleaner UVs. As more teams adopted these tools, conventions solidified—consistent texel density, atlas naming, padding rules, and versioning—making UV management teachable, scriptable, and automatable without losing the artistry at the heart of texturing.

High‑resolution texturing and alternatives

Film and high‑end visualization pushed resolution beyond what single textures could handle gracefully. Weta Digital introduced the UDIM tile convention to spread a single asset’s textures across multiple numbered tiles, preserving intuitive 0‑1 addressing within each tile while allowing virtually unlimited coverage. The Foundry’s Mari, developed for feature‑film needs, popularized UDIM in production with a painting workflow that treated tiles as natural extensions of the canvas. Product visualization teams later embraced UDIM for hero surfaces—automotive exteriors, watch cases, footwear uppers—where ultra‑high resolution and local detail mattered.

In parallel, Disney researchers Brent Burley and Dylan Lacewell proposed Ptex, a per‑face texturing approach that eliminated UVs by storing and filtering textures over individual faces, each with its own resolution. Ptex sidestepped seam management and packing altogether and found wide support in VFX renderers. However, outside VFX, particularly in CAD‑centric pipelines, Ptex adoption remained limited due to interoperability concerns, asset exchange expectations, and the need to interface with decal/label workflows. Sculpt‑to‑texture tools provided yet another path: ZBrush Polypaint and Pilgway’s 3D‑Coat let artists paint directly on high‑poly meshes, then bake color, normals, and displacements down to UV textures. These alternatives did not replace UVs wholesale but enriched the toolbox, offering pragmatic choices: UDIM for scale, Ptex for simplicity where pipelines allowed, and sculpt workflows when organic fidelity trumped rigid repeatability. Together, they expanded the concept of “texture space” from a single atlas into a family of strategies aligned with the demands of cinema, games, and industry.

Product visualization matures: PBR, measured materials, and CAD integration

PBR becomes the lingua franca

The leap from plausible to predictable materials arrived with physically based rendering. Disney’s principled BRDF distilled a complex body of scattering theory into a pragmatic set of artist‑friendly controls that respected energy conservation and microfacet behavior. This model crystallized today’s metal/rough workflows and set a common expectation for how base color, roughness, metallic, normal, and ambient occlusion maps combine. The Khronos Group cemented portability with glTF 2.0, which standardized a core PBR material in an exchange format tuned for real‑time and the web, enabling consistent looks across engines and devices. Beyond exchange, material graphs became shareable assets. NVIDIA’s MDL offered a descriptive language for materials that could be evaluated across different renderers, while ILM’s MaterialX, incubated in the Academy Software Foundation, established open schemas for node‑based looks. Pixar’s USD/USDShade extended this portability to scene graphs, connecting materials to geometry in robust, layerable ways.

The cumulative effect was a lingua franca in which materials were no longer renderer‑locked recipes but portable, semantically rich descriptions. For product visualization, this meant CAD assemblies could carry materials from ideation to marketing with fewer reinterpretations. Teams could rely on consistent Fresnel behavior, microfacet distributions, and texture usage across viewport and final frames. As PBR percolated into engines from Unreal to enterprise tools, texturing practices followed suit: UV mapping served as the backbone for physically meaningful textures rather than ad‑hoc image placements, and procedural layers could be evaluated predictably regardless of the rendering backend. This convergence simplified collaboration and reduced surprises, anchoring photorealism not in tricks but in shared physics.

Texture authoring and libraries industrialize

The democratization of material quality arrived with Allegorithmic’s pair of tools, Substance Designer and Substance Painter, led by Sébastien Deguy and later acquired by Adobe. Designer brought node‑based, procedural authoring for materials that could be parameterized, versioned, and reused; Painter combined baking pipelines with smart masks and generators that understood curvature, ambient occlusion, and thickness maps. Together, they turned texture authoring into a repeatable, data‑driven process suitable for product teams who must manage hundreds of variants and late‑stage changes. Libraries expanded dramatically: Quixel’s Megascans delivered scan‑based SVBRDFs with properly captured albedo, normal, roughness, and sometimes height, setting a new baseline for authenticity in woods, stones, fabrics, and metals.

Pragmatism softened UV pain where appropriate. Triplanar projection reduced stretching for irregular surfaces without meticulous unwrapping, and non‑destructive decal/projection mapping made labels and regulatory markings a late‑stage operation instead of a risky UV surgery. Authoring workflows increasingly looked like software engineering:

- Parametric materials with exposed controls for gloss, flake size, and tint.

- Bakes for normal, curvature, position, and thickness driving procedural masks.

- Template‑driven atlases and UDIM sets for product families.

- Style guides encoded as layered presets that travel across teams and renderers.

This industrialization shifted focus from pixel pushing to intent capture. Designers specified “what” (anodized aluminum, matte ABS, satin leather) while tools computed “how” across resolutions and platforms. UVs remained central but more concealed: a substrate over which procedural logic and measured data could operate consistently, with the freedom to adjust layout late without discarding material intelligence.

Measured appearance enters the studio

The last mile to convincing realism is measurement. X‑Rite’s AxF format and TAC7 capture system, alongside Vizoo’s fabric scanners and various BRDF/BSDF measurement rigs, brought metrology‑grade appearance data into everyday practice. Instead of approximating sparkle, anisotropy, or subsurface bloom, teams could ingest measured coatings, leathers, and textiles that behaved correctly under changing illuminants and view angles. This was particularly transformative for automotive paints, pearlescent finishes, and woven fabrics where microstructure dominates the look. Import pipelines translated measurements into renderer‑friendly models while preserving key perceptual attributes like gloss response and flake orientation.

Renderer support proliferated across visualization tools used in design and marketing: KeyShot from Luxion (founded by Claus and Henrik Wann Jensen), Autodesk VRED (originating at PI‑VR), Dassault Systèmes 3DEXCITE DELTAGEN (ex‑RTT), SolidWorks Visualize (ex‑Bunkspeed, powered by Iray), Siemens NX Ray Traced Studio (Iray), and prominent offline engines such as V‑Ray (Chaos; Vlado Koylazov), Arnold (Marcos Fajardo), Octane (OTOY; Jules Urbach), and Redshift (Maxon). These engines absorbed layered BRDFs, spectral IORs, and multi‑lobe GGX variants to honor measured inputs. The change was cultural as much as technical: CMF teams started maintaining libraries of measured materials as institutional assets, versioned alongside CAD. Texture maps became carriers of real‑world truth rather than hand‑tuned approximations, and UV layouts were designed to accommodate tiling scales and anisotropic directions encoded in measured samples. The entire workflow aligned around fidelity: capture accurately, map consistently, and render predictably.

CAD‑to‑viz realities

Between pristine NURBS and a rendered frame lies a minefield: tessellation. Re‑tessellating CAD surfaces for different LODs or tools can break UV continuity, shift island boundaries, and scramble vertex orders. Robust pipelines therefore prioritize UV transfer strategies and part‑consistent texel density, ensuring that materials survive iterative design without perceptual drift. This involves choosing seam strategies that track with topological features unlikely to change, and adopting naming conventions for islands and UDIM tiles that persist across CAD updates. Packaging and CMF workflows lean on simple projections—planar, cylindrical, spherical—for high‑confidence label placement, while reserving UDIM for hero surfaces where minute control and resolution are paramount.

Color fidelity threads through the process. From Pantone targets to emerging spectral models, consistent color management ensures that the same red remains the same red from design review to brochure. Practical steps include:

- Embedding ICC profiles and adopting scene‑referred workflows with view transforms.

- Relying on spectral or wavelength‑aware renders for metallic flakes and interference pigments.

- Maintaining scale metadata to keep microstructure (grain, weave, flake size) physically meaningful.

- Standardizing UV scale conventions so decals and textures transfer between variants.

Ultimately, CAD‑to‑viz integration is about preserving intent: geometric, material, and visual. UVs serve as continuity tissue between tessellations, renderers, and revisions. When paired with tile conventions like UDIM, portable graphs like MaterialX or MDL, and measured materials in AxF or similar formats, they let product teams iterate quickly without paying an authenticity tax at each handoff.

Conclusion

From theory to pipelines

In the span of a few decades, UV mapping traveled from the theoretical elegance of parameter spaces to the everyday pragmatism of industrial pipelines. Catmull’s per‑surface coordinates, Blinn’s shading tricks, and Williams’ mipmapping made images stick to surfaces without falling apart. LSCM and ABF++ domesticated distortion so artists and engineers could unwrap at scale, while Sander‑style metrics turned quality into something measurable. UDIM opened the floodgates for film‑scale detail and then quietly became standard practice in product visualization. Meanwhile, the ubiquity of UV editors and 3D painting tools put powerful, understandable controls in the hands of practitioners who needed to balance precision with speed.

On the material side, PBR turned renderer‑specific recipes into portable, physics‑aware descriptions. The triad of MaterialX, MDL, and USD/USDShade provided interoperable graphs and bindings, while glTF 2.0 made real‑time delivery consistent on the web and in lightweight viewers. Measured appearance closed the realism gap: AxF, TAC7, and fabric scans meant plastics, paints, and textiles behaved like themselves under real light. Across this evolution, UVs remained the canvas—sometimes tiled, sometimes abstracted away by Ptex or flooding with procedural noise—but always present as the reliable coordinate frame where image, math, and manufacturing intent could meet.

The road ahead

The next wave points to both simplification and sophistication. Expect AI‑assisted unwrapping to propose seam placements and island groupings optimized for distortion, painter workflow, and decal placement, while machine learning aids in texture synthesis that respects material statistics and manufacturing constraints. USD’s continued spread into CAD, coupled with deeper adoption of MaterialX, will sharpen cross‑tool consistency, from viewport previews to high‑end offline renders. Rendering will lean more spectral and more appearance‑accurate, honoring complex pigments and fabric microgeometry; visual comfort will benefit from better tone mapping and glare models that match human perception.

At the same time, pipelines will grow more selective about where UVs are necessary. Ptex and procedural materials will carve out zones where hand‑placed islands add little value, while UDIM and meticulous layout will remain indispensable on branded surfaces and packaging. The long‑term challenge stays pragmatic: automate robust mapping on CAD tessellations, preserve intent across revisions, maintain CMF libraries as living assets, and keep color‑managed truth at the center from design to marketing. The enduring lesson of UVs is not that every surface must be flattened, but that every surface must be addressable—predictably, portably, and with enough fidelity to carry the story of the product from parameter spaces to pixels.

Also in Design News

Rhino 3D Tip: Validate Curvature and Surface Fairness in Rhino

December 15, 2025 2 min read

Read More

Path-First Modeling: Embedding Toolpath-Aware Constraints and Fabrication Primitives into CAD Kernels

December 15, 2025 13 min read

Read More

Coupled Thermal–Structural–Acoustic Modeling and Optimization: A Pragmatic Playbook for Multiphysics Design

December 15, 2025 14 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …