Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

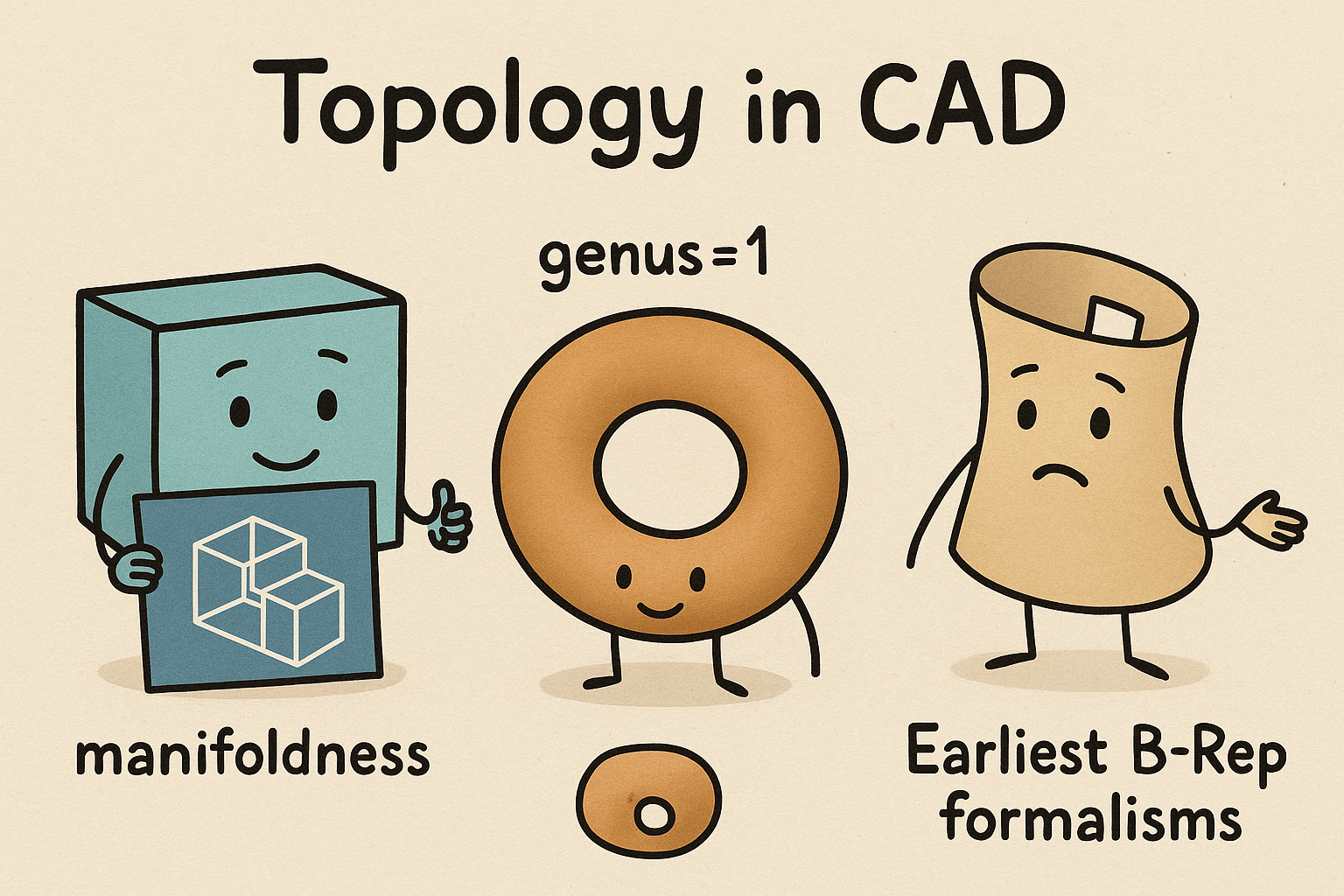

Design Software History: Topology in CAD: Manifoldness, Genus, and the Earliest B‑Rep Formalisms

January 02, 2026 14 min read

Why topology matters in CAD: manifoldness, genus, and the earliest formalisms

From geometry to computable contracts

In computer-aided design, topology is the invisible contract that makes geometry computable, manufacturable, and trustworthy across downstream processes. A model that merely “looks right” is insufficient if its topological fabric is incoherent. Designers and engineers lean on the discipline’s staples—closed, 2‑manifold shells, consistent orientation, and sane counts of vertices, edges, and faces—to guarantee that what they draw can be reliably intersected, meshed, offset, or printed. These rules are not academic niceties; they directly determine whether Boolean operations converge, whether a finite element mesher can produce a conforming grid, and whether a slicer will generate closed contours for additive manufacturing. In practice, topology acts as the guardrail at every stage of the CAD→CAE→CAM chain, preventing geometric flourishes from collapsing into numerically fragile artifacts.

When early CAD migrated from stylus-and-curves to solids, researchers understood that “solidity” is fundamentally topological. You need more than curved patches; you need explicit adjacency—faces bounded by oriented edges meeting at vertices—and you need a way to audit that structure. The field’s foundational work from the 1970s to 1980s made those ideas executable, establishing data structures and validity criteria that still underpin today’s commercial kernels. From winged-edge to radial-edge, from regularized Boolean algebra to Euler operators, the central story is consistent: encode topology explicitly, then pair it with analytical geometry (planes, cylinders, NURBS) to form robust solid models that behave under transformation, trimming, and evaluation.

Core notions designers actually rely on

Manifoldness, orientability, shells, and sanity checks

The day-to-day health of a CAD model is governed by a handful of topological notions that—once internalized—explain why some models sail through downstream tools while others crumble. The first is manifoldness. A solid worthy of the name has a boundary that is a 2‑manifold surface: every edge is incident to exactly two faces, and the local neighborhood looks like a disk, not a T‑junction. This ensures a unique “inside” and “outside,” enabling watertightness and well-defined Booleans. Paired with manifoldness is orientability: faces carry normals that collectively point outward from the solid; consistent orientation allows offsetting for CAM toolpaths and accurate shelling or thickness analysis. Finally, designers distinguish closed shells (no boundary) from bounded open sheets used for surfaces or midsurfaces; for solids, closed shells are a non-negotiable precondition.

Two compact checks keep models honest. Genus counts “handles”—a torus has genus 1, a double torus genus 2—capturing hole topology independent of geometry. The Euler–Poincaré relation ties counts of vertices (V), edges (E), faces (F), shells, and genus (g) so kernels can detect invalid edits: loosely, V − E + F equals 2 − 2g for a single closed orientable shell, with extensions for multiple shells and voids. Why this matters becomes obvious in use: Boolean correctness depends on consistent boundary orientation; FEA/CFD meshing needs watertightness and no dangling edges; CAM offsetting and collision detection rely on coherent normals; and printability in AM is a direct consequence of manifold boundary models. Practical red flags—nonmanifold T‑edges, self-intersections, inverted normals—map to these ideas, which is why most professional tools expose checks that enforce or repair them.

- Boolean reliability: regularized set ops assume manifold, oriented inputs.

- Meshing robustness: watertightness and no self-intersections prevent failed tets or skewed boundary triangles.

- CAM offsets: consistent normals enable safe tool compensation and gouge checks.

- AM printability: closed, correctly oriented shells slice into closed polylines with predictable infill.

Foundational academic milestones that linked topology to computable models

From winged-edge to B-rep semantics

The modern solid modeler rests on a series of precise breakthroughs that turned topology into data structures and algorithms. In 1972, at Stanford’s AI Lab, Bruce G. Baumgart introduced the winged-edge structure, encoding for each edge the adjacent faces and neighboring edges on both “wings.” With explicit adjacency, algorithms could traverse boundaries, compute neighborhood relations, and implement Euler operators that preserve validity. Through the mid‑1970s and into the 1980s, A. A. G. (Ari) Requicha and Hervé (Herb) B. Voelcker at the University of Rochester rigorously defined the formal semantics of Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG), advocating regularized Booleans to avoid pathological lower-dimensional remnants and articulating validity conditions that map cleanly to manufacturable solids.

By the late 1980s, Kevin Weiler generalized adjacency with the radial-edge structure, allowing edges to be incident to more than two faces—key for non-manifold modeling—while still supporting manifold substructures. In parallel, Martti Mäntylä at Helsinki University of Technology codified boundary representation theory, validity, and Euler operators in his 1988 book “An Introduction to Solid Modeling.” Mäntylä’s synthesis drew a sharp line between geometry (analytic or spline surfaces and curves) and topology (faces/edges/vertices with orientation and incidence), showing how kernels can maintain global consistency through local edits. Together, these contributions transformed topology from a conceptual backdrop into a programmable substrate, enabling robust B‑rep modelers to become the industry’s default for mechanical CAD and a foundation for today’s interoperability standards.

Early models and their limits

Wireframes, patchwork surfaces, and the push to solids

Early CAD systems emphasized curves and wireframes because they were computationally accessible and aligned with drafting practice. But a wireframe has no faces; it cannot define interior versus exterior, and it permits contradictory topologies on the same set of edges. The result is ambiguity: hidden-line removal, mass properties, and Booleans are ill-posed because the model lacks a boundary. The subsequent surface era introduced analytic patches and, later, NURBS with remarkable geometric fidelity—fillets, Class‑A curves, and reflectance-friendly continuity. However, without explicit topological closure, surface models remained visually impressive but topologically underdetermined. Designers had to stitch, trim, and sew patches into shells, battling gaps at tolerance boundaries and mismatched parameterizations.

These limitations pushed development toward explicit, watertight B‑reps. The community realized that leaving topology implicit forces downstream tools (meshing, offsets, Booleans) to guess at adjacency and orientation—an approach doomed by numerical noise and edge mismatches. In practice, surface modelers sprouted solid modules that added shell/void semantics, while dedicated solid kernels made topology first-class. The shift rendered previously fragile operations predictable: mass properties became integrals over closed boundaries, toolpath gouge checks used outward normals, and meshing could enforce edge-conformity. Wireframes and pure surfaces still matter for conceptualization and styling, but the engineering backbone is unequivocally a topology-explicit approach.

- Wireframe: fast, intuitive, but topologically ambiguous; no volumes, no watertightness.

- Surface/NURBS: high geometric fidelity; requires trimming, sewing, and oriented shells to achieve solidness.

- Solid B‑rep: explicit faces/edges/vertices with incidence; supports Booleans, meshing, and manufacturing semantics.

B-rep vs CSG (and hybrids)

Two pillars of solid modeling and why they converge

Boundary representation (B‑rep) stores topology (faces, edges, vertices, shells, and their orientation) and associates each topological entity with geometry (planes, cylinders, cones, NURBS surfaces/curves). B‑reps excel at local edits—fillets, chamfers, drafts—because operations map to well-defined topological neighborhoods. They are the lingua franca of downstream processes: tessellation for visualization, watertight boundary extraction for CAE meshes, and offsetting for CAM all begin from oriented faces and edges. In contrast, Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG) builds models as trees of primitives (blocks, spheres, extrusions) combined by regularized Boolean operators and rigid transforms. CSG’s strength lies in its algebraic clarity—ontologically solid by construction—and its amenability to procedural and parametric definitions.

In industry, the two approaches meet in hybrid kernels. CSG offers a robust, high-level specification that captures design intent; evaluation produces a B‑rep with explicit topology for visualization, simulation, and manufacturing. Conversely, B‑reps often embed procedural histories akin to CSG, enabling feature replay on parameter change. The core message is pragmatic: work in B‑rep when you need local topology-aware edits and interoperability; leverage CSG when constructive hierarchies simplify modeling and ensure set-theoretic correctness. Most leading kernels implement both: they maintain precise boundary graphs, while their feature systems preserve constructive semantics, often re‑evaluating a CSG‑like specification to regenerate the B‑rep whenever parameters change.

- B‑rep strengths: local editability, explicit adjacency, downstream compatibility.

- CSG strengths: parametric clarity, guaranteed regularity, compact procedural definitions.

- Hybrid reality: specification as CSG/feature tree; evaluation to watertight B‑rep.

Commercialization and the kernel lineage

From ROMULUS to Parasolid, ACIS, CGM, Granite, and OCCT

The consolidation of topology into industrial CAD happened through commercial kernels—shared geometric modeling engines licensed across products. In Cambridge (UK), Shape Data under Ian Braid created ROMULUS, one of the first robust B‑rep kernels, laying groundwork for Parasolid. Parasolid, eventually under UGS and now Siemens Digital Industries Software, became a backbone for Unigraphics/NX and a broadly licensed core for products like SolidWorks, Solid Edge, and Onshape. In the U.S., Spatial Corp, founded by Dick Sowar, introduced ACIS in 1989, focusing on componentized modeling services; Dassault Systèmes later acquired Spatial. Autodesk forked ACIS in the early 2000s to create ShapeManager for Inventor, tailoring robustness and interoperability for its ecosystem.

Dassault Systèmes meanwhile invested in its in‑house CGM kernel, the engine beneath CATIA V5/V6 and 3DEXPERIENCE apps; interestingly, SolidWorks—owned by Dassault—continues to run on Parasolid, demonstrating the pragmatic mix of kernels within one company’s portfolio. PTC developed the Granite kernel used in Pro/ENGINEER and Creo, with an emphasis on associative parametrics and feature‑level persistence. On the open-source front, Open CASCADE Technology (OCCT) has become the go‑to for research and specialized industrial tools, powering platforms like SALOME and FreeCAD. These kernels encode decades of topological wisdom: stable Booleans, tolerant modeling, exact/approximate intersections, and persistent identities. Their histories mirror the discipline’s maturation from academic constructs to hardened industrial infrastructure.

- Parasolid: robust B‑rep/CSG hybrid; wide third‑party licensing; Siemens NX native.

- ACIS/ShapeManager: modular services; Autodesk fork for tuned robustness.

- CGM: Dassault’s in‑house kernel for CATIA/3DEXPERIENCE.

- Granite: PTC’s parametric‑centric kernel for Creo.

- OCCT: open-source B‑rep stack with strong topology and meshing utilities.

Standards baked with topology

From IGES surfaces to STEP AP242 solids and PMI

Interoperability reveals whether topology is first-class or an afterthought. IGES, the earliest widely adopted exchange standard, prioritized curves and surfaces with limited, vendor‑specific conventions for solids. As a result, IGES often degraded watertight models into surfaces, losing shell semantics and requiring laborious healing upon import. The successor, STEP (ISO 10303), put topology at the center. Application protocols AP203 and AP214 introduced explicit entities for shells, faces, edges, and orientations, while preserving parametric surfaces and curves. The consolidation into AP242 unified mechanical design scope and added PMI for MBD—semantic product manufacturing information anchored to topological entities—so tolerances, GD&T, and annotations travel with the model, not as detached drawings.

By encoding topological identity and orientation, STEP enables reliable roundtrips across kernels: a closed shell in one system remains a closed shell in another, with persistent references that downstream CAE and CAM consumers can trust. AP242’s emphasis on assembly structure, kinematics, and PMI further cements topology’s role: annotations and mating conditions bind to faces and edges, not pixelated triangulations. While tessellated flavors of STEP exist for lightweight visualization, the standard’s heart is the boundary graph—because that is what supports traceable engineering decisions across toolchains and decades of product lifecycle management.

- IGES: strong for curves/surfaces; weak/topology-light for solids; import healing common.

- STEP AP203/AP214→AP242: explicit shells/faces/edges with orientation; mature assembly/PMI support.

- MBD/PMI: tolerances and GD&T semantically tied to topological entities for downstream automation.

Legitimate non-manifold use cases

When breaking manifold rules is the correct model

While 2‑manifold boundaries define conventional solids, engineering practice includes cases where non‑manifold topology is purposeful. Sheet‑metal flanges meeting along a shared edge, weld beads modeled as intersecting skins, or midsurface idealizations in CAE intentionally produce T‑junctions and edges incident to more than two faces. Additive manufacturing introduces further needs: lattice structures and triply periodic minimal surfaces can intersect in ways that, if collapsed to a single boundary, would be unwieldy or lossy. Multi‑physics networks—fluid, thermal, or electrical conduits embedded in solids—also benefit from non‑manifold representations that encode branching in the topology.

Data structures evolved to support this reality. Kevin Weiler’s radial-edge accommodates multiple faces around an edge, and research‑origin non‑manifold topology (NMT) schemes have entered production in CAE preprocessors and AM lattice design tools. Industrial CAD often enforces manifoldness in core solids but allows non‑manifold submodels within analysis or manufacturing contexts, exchanging them via specialized formats or kernel extensions. The key is intentionality: non‑manifold features should be explicit, localized, and accompanied by semantics so downstream tools understand whether to thicken, idealize, or ignore them. By acknowledging these legitimate uses, modern toolchains avoid forcing artificial manifold “fixes” that would erase design intent or introduce numerical artifacts.

- Sheet metal and welds: shared edges and skins model fabrication reality.

- CAE midsurfaces: efficiency and fidelity for thin parts necessitate non‑manifold junctions.

- AM lattices: graph‑like struts intersecting across volumes defy simple manifold closures.

- Multi‑physics networks: branching topologies encode physical flows within solids.

Mesh pipelines and the “triangle soup” problem

STL’s ubiquity, its limits, and richer successors

The most pervasive file in additive manufacturing remains STL, originally popularized by 3D Systems during Chuck Hull’s stereolithography era. STL describes surfaces as independent triangles without explicit adjacency or orientation beyond per‑triangle normals. This simplicity made STL universal—but it also birthed the “triangle soup” problem: holes, inverted normals, self‑intersections, duplicated faces, and dangling edges are common, forcing slicers and repair tools to infer topology from fragmentary clues and tolerances. As a result, print pipelines frequently hinge on “healing,” a process that guesses at closed shells and manifoldness, sometimes changing model intent.

Newer standards tackle these gaps. AMF (ISO/ASTM 52915) introduces units, materials, lattices, and instances; 3MF, driven by the 3MF Consortium (Microsoft, Autodesk, Dassault Systèmes, Siemens, and others), provides richer structure for materials, build items, and assembly semantics, and encourages manifold correctness. Yet even with better containers, many workflows ingest legacy STL. A substantial ecosystem has grown around repair: Materialise Magics, Autodesk Netfabb and Meshmixer, “Import Data Doctor” in PTC Creo, healing/defeaturing tools in CATIA/3DEXPERIENCE, Siemens NX, and Autodesk Inventor/Fusion. The lesson is consistent with B‑rep practice: topology should be explicit, not inferred. When meshes carry adjacency (half‑edge structures) and orientation, they behave predictably; when they don’t, every downstream step pays a robustness tax.

- STL: adjacency‑free; easy to produce; costly to validate and heal.

- AMF/3MF: richer semantics (materials, instances, units); better assembly and manifold support.

- Healing tools: automate watertightness, normal consistency, and self‑intersection fixes.

Robustness and numerical reality

Epsilon-geometry, exact predicates, and integrity-preserving edits

The clean topological laws meet messy numerics in kernels built on floating‑point arithmetic. Real systems wrestle with tolerances: edges that barely meet, surfaces that should intersect but miss by microns, and round‑off errors that accumulate across feature edits. Classic “epsilon-geometry” tolerates small inconsistencies, merging entities within a set threshold—practical but potentially ambiguous. A complementary strand uses exact predicates to answer topological questions (orientation tests, incircle tests) robustly despite floating‑point inputs. Jonathan Richard Shewchuk’s robust predicates and exact arithmetic paradigms inspired libraries such as CGAL, whose Nef polyhedra model supports exact Booleans on polyhedra with rigorous topology tracking.

On the edit side, Euler operators provide a structured way to ensure validity: each operation (make edge‑face, kill face‑edge, split face, merge shells) changes the boundary while preserving the Euler–Poincaré invariants, keeping genus and shell counts consistent. Kernels pair these operators with intersection and trimming algorithms that respect tolerances but produce coherent adjacencies. Integrity checks—tracking genus, voids, and shell connectivity—guard against silent corruption during sequences of fillets, drafts, and patterns. The upshot is a hybrid philosophy: use exactness where it disambiguates topology; use tolerances where geometry must be pragmatic; and always revalidate the boundary graph after operations that can create small slivers or near‑tangencies.

- Exact predicates: robust orientation/incircle decisions prevent topological flips.

- Tolerant modeling: merges nearly coincident entities to maintain model continuity.

- Euler operators: guarantee topological validity through local edits.

- Integrity tracking: monitor genus and shell connectivity to catch drift early.

The topological naming problem (when faces won’t keep their names)

Persistent identity across parametric change

Parametric CAD assumes features can be edited and recomputed with downstream references intact: sketches dimension to faces; mates anchor to edges; PMI attaches to surfaces. But when topology changes—say a fillet deletes a face and creates several new ones—those references can break or silently retarget in surprising ways. This is the infamous topological naming problem. Adrien Kripac articulated a seminal approach to persistent naming, proposing strategies to assign stable identities that survive typical transformations. Vendors have deployed a mix of techniques: specification‑driven rebuilds that recompute from a high‑level feature tree; “intent” references that prefer faces by geometric role (largest planar face, cylindrical hole axis) rather than raw IDs; and internal stable‑ID schemes that encode construction history and adjacency context.

Despite progress, it remains an active research and product area because topological changes can be combinatorial. Pattern features, Boolean splits, and draft/fillet cascades cause faces to bifurcate or vanish in ways that defy deterministic naming. The direction of travel is clear: kernels and standards need closer coupling so identity can be preserved and communicated beyond one system. STEP AP242’s PMI anchored to faces makes stability crucial; without robust naming, downstream CAE setups, CAM operations, and MBD annotations risk invalidation on every parameter tweak. The best mitigations blend heuristics with user‑visible “intent” controls and repair tools that pinpoint broken references and offer semantically guided reattachment.

- Specification-driven rebuilds: derive identity from the feature tree, not ephemeral IDs.

- Intent references: bind by geometric role (e.g., primary datum plane) rather than index.

- Stable-ID schemes: encode construction context and adjacency to improve persistence.

The throughline

How manifoldness and genus became the core of modern kernels and standards

From early formalisms to today’s kernels, the throughline is that manifoldness, orientation, and genus migrated from blackboard topology to the heart of industrial software. Winged‑edge and radial‑edge let kernels encode adjacency; Requicha and Voelcker’s regularized CSG ensured set‑theoretic cleanliness; Mäntylä’s B‑rep theory and Euler operators made validity programmable. Those ideas hardened into commercial engines—Parasolid, ACIS/ShapeManager, CGM, Granite, and OCCT—that guarantee watertight boundaries, stable Booleans, and orientation‑aware offsets. In parallel, STEP AP242 embedded shells, faces, and edges with orientations into the standard record of product data, while PMI bound tolerances and annotations to those entities.

Because topology is explicit and validated, modern design flows are predictable: mass properties agree across tools; meshing honors part boundaries; toolpaths offset correctly; and AM slicers generate closed contours. Even when workflows detour into meshes or non‑manifold idealizations, the topological lens guides conversion, healing, and exchange. The success of contemporary CAD is not accidental geometric polish—it is decades of making topology computable, auditable, and central to every operation that matters in engineering.

- Kernels operationalize manifold boundary graphs and Euler‑safe edits.

- Standards carry explicit topology and PMI across organizational and temporal boundaries.

- Downstream tools depend on coherent topology for simulation, planning, and fabrication.

Interoperability stakes

Why explicit, correct topology makes translation and downstream trust possible

Interoperability is only as reliable as the model’s topology. If faces, edges, and shells are explicit and oriented, translation between kernels can preserve identity, and downstream CAE/CAM consumes predictable boundaries. This is where STEP AP242 changed the game: by standardizing topological entities and their relationships, it removed guesswork that plagued IGES‑based exchange. For MBD/PMI, the stakes are higher—tolerances, datum schemes, and GD&T must adhere to specific faces or edges so inspection plans and NC programming can be generated automatically. Without stable topological anchors, these semantics drift or break, undermining digital continuity.

STL’s lingering popularity in AM reminds us what happens when topology is left implicit. Simple meshes are fine for visualization and quick prints, but they are brittle for engineering. Richer containers like 3MF and AMF help, yet the ideal is a watertight B‑rep or an adjacency‑aware mesh that round‑trips intact. Enterprises now treat topology as part of their data governance: models are validated at check‑in; repair summaries are logged; and PMI conformance is audited before release. The result is fewer surprises—from simulation meshes to shop‑floor toolpaths—because the geometry’s topological skeleton is unambiguous and shared across the toolchain.

- Translation fidelity: explicit shells/faces/edges survive kernel boundaries.

- MBD/PMI trust: semantic dimensions remain bound to the intended surfaces.

- AM reliability: adjacency‑aware representations reduce print failures and post‑healing.

Where it’s heading

Hybrid models, topology-aware automation, and persistent identity at scale

The frontier blends classical topology with volumetric and field‑based representations. Kernels are incorporating implicit fields (signed distance functions), voxels (OpenVDB grids), and function‑based representations (FRep) alongside B‑reps, enabling graded materials, conformal lattices, and metamaterials that defy simple surface descriptions. Tools such as nTopology exemplify workflows where fields generate structures later intersected with B‑rep boundaries, with resolidification that preserves manifoldness. The promise is a hybrid stack: use B‑rep for interfaces and datum‑critical geometry; use fields/voxels for interior complexity; connect them through robust evaluation that yields watertight boundaries for manufacturing.

Automation is likewise topology‑aware. Generative design and topology optimization increasingly produce manufacturable, guaranteed‑manifold outputs directly, informed by print process constraints and minimum feature sizes. The algorithms must emit consistent topological identity through edits so that PMI, CAE loads, and CAM strategies remain attached. Long‑term, expect tighter coupling between kernels and standards: extensions to STEP AP242 for hybrid representations; richer identity schemes that carry stable face/edge references across revisions; and archival strategies that preserve both construction history and topological anchors for decades. The arc bends toward models whose topology is explicit, resilient under change, and expressive enough to describe the next generation of engineered materials and products.

- Hybrid B‑rep + field/voxel: best of both—clean interfaces and rich interiors.

- Topology‑aware generative tools: optimization that respects manifoldness and process limits.

- Persistent identity: kernel/standard cooperation to keep references stable over time.

Also in Design News

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …