Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History: Simulation-Based Generative Design: Origins, Algorithms, Representations, and Manufacturability

December 04, 2025 12 min read

Origins and definitions: how simulation-based generative design emerged

Definition and scope: coupling physics with search under manufacturability

Within engineering software, simulation-based generative design describes the practice of coupling physics solvers with optimization to automatically propose geometries that meet performance goals while respecting manufacturing, cost, and regulatory constraints. The loop is straightforward in spirit and demanding in execution: engineers define a design space, material options, and boundary conditions; solvers compute structural, fluid, or thermal responses; and optimization engines explore the vast shape and topology space, converging on families of manufacturable candidates. What sets modern platforms apart is that “design intent” extends beyond compliance or temperature to include explicit production realities such as minimum printable feature size, tool reach, surface finish, build orientation, and secondary operations. The design variable is not just a handful of dimensions—it is a high-dimensional field that encodes material distribution, lattice gradation, and local process constraints. This shift turns simulation from a post hoc verification step into a creative partner that suggests viable, high-performing shapes.

- Physics engines commonly embedded: linear/nonlinear FEA for stress, buckling, and vibration; CFD for pressure drop and drag; conjugate thermal for heat dissipation; and, increasingly, multiphysics couplings.

- Optimization frameworks span gradient-based (adjoint-enabled) methods for speed and precision, multi-objective genetic algorithms for discrete choices, and Bayesian strategies for expensive trade spaces.

- Manufacturability rules include additive constraints (overhang control, support cost), subtractive rules (2.5D machinability, draft), and hybrid pathways with post-processing.

In practice, this means an engineer can ask the system to minimize mass under multiple load cases and fatigue targets, cap pressure drop, meet thermal comfort, and guarantee manufacturable geometries for a specified process, all while staying under a cost ceiling. The output is not merely one optimal part but a curated set of trade-offs that align with bill-of-process realities and downstream CAD/CAM needs.

Foundations in the 1980s–2000s: from SIMP to level-sets

The intellectual groundwork was laid by the topology optimization community. In the late 1980s, Martin P. Bendsøe and later Ole Sigmund formalized the SIMP (Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization) density method, which relaxes binary material assignment into a continuous “density” variable and gradually penalizes intermediate values to recover crisp structure. Krister Svanberg’s MMA (Method of Moving Asymptotes) supplied a robust, quasi-Newton optimizer that behaves well on large-scale, constrained problems, becoming the de facto engine in many research and industrial codes. In parallel, Mike Xie and Gui-Rong Steven advanced ESO/BESO (Evolutionary Structural Optimization/Bi-directional ESO), popularizing simple heuristics for removing and adding material guided by element sensitivities. These pillars collectively made large, production-scale material layout feasible and illuminated how to handle mesh dependency, checkerboarding, and minimum member size via filters and projections.

By the early 2000s, researchers such as Grégoire Allaire pushed level-set techniques that evolve interfaces via Hamilton–Jacobi equations, enabling smoother boundaries and better stress control at the cost of more involved numerics. The broader computational mathematics community, influenced by Stanley Osher and James Sethian’s work on level-sets and fast marching, led to practical curvature control and boundary regularization. Commercialization gathered pace: Altair OptiStruct brought topology and size/shape optimization into production at automotive and aerospace suppliers; Ansys and Abaqus integrated topology methods with their established FEA stacks. These years also saw the emergence of adjoint methods in fluid and thermal optimization, seeding later multiphysics orchestration. Crucially, the narrative remained solver-centric: optimization lived close to FEA/CFD kernels, and CAD was a downstream recipient that often struggled to robustly reconstruct organic shapes.

2010s popularization and the representation pivot

The 2010s reframed the field as “generative design,” expanding from single-physics topology layout to multi-objective, manufacturability-aware exploration. Autodesk’s Project Dreamcatcher—spearheaded by Erin Bradner and Mark Davis—demonstrated cloud-scale iteration and later matured into Fusion 360 Generative Design, which blended optimization with DFM filters and automatic CAD reconstruction. In the startup ecosystem, Frustum, led by Jesse Coors-Blankenship, shipped Generate and the TrueSOLID kernel, emphasizing smooth CAD reconstructions from voxel fields; PTC acquired Frustum and folded its capabilities into Creo. ParaMatters launched CogniCAD, later acquired by Carbon, underscoring end-to-end additive flows. Dassault Systèmes brought Function-Driven Generative Design into CATIA/3DEXPERIENCE, while Siemens integrated NX/Simcenter workflows with automated study orchestration. nTopology championed field-driven modeling—scalar/vector fields that define material, lattice, and metamaterial behavior—showing that implicit fields can carry engineering semantics, not just visuals.

Technically, this period marks a representation pivot. Traditional CAD systems centered on B-rep and NURBS surfaces; generative platforms increasingly operate on voxel, level-set, and implicit fields during optimization, then reconstruct high-quality CAD. GPU acceleration (CUDA solvers, RTX/OptiX visualization), elastic cloud resources on AWS/Azure/GCP, and web-first CAD (e.g., Onshape’s platform with cloud FEA partners) made thousands of candidate evaluations feasible. The rhetorical shift from “topology optimization” to “generative design” reflects a real distinction: the latter orchestrates objectives, constraints, manufacturability, data management, and return-to-CAD in a cohesive decision system rather than a single optimizer wrapped around FEA.

Hybrid algorithmic landscape: combining gradients, search, and learning

Gradient-based cores: SIMP, adjoints, and level-set evolution

At the heart of many pipelines sit gradient-based engines that exploit adjoint sensitivities to compute derivatives of objectives and constraints with respect to millions of design variables at near-constant cost, independent of variable count. The SIMP density method remains a workhorse, aided by sensitivity filters and Heaviside projections to enforce minimum feature sizes and suppress checkerboards. Move limits and continuation strategies stabilize convergence under multiple load cases and path-dependent material models. MMA—a stalwart from Krister Svanberg—still powers many industrial codes; sequential quadratic programming (SQP) and projected gradient variants also appear where constraint sets remain smooth. For boundary-smooth outputs and better stress control, level-set methods advance the material interface through Hamilton–Jacobi PDEs, often with curvature regularization to avoid spurious features.

- Strengths: near-real-time sensitivity computation, precise constraint handling (stress, frequency, buckling), and predictable convergence when the landscape is smooth.

- Limitations: challenges with discrete variables (fastener count, stock sizes), non-differentiable penalties (support removal cost), and rugged, multi-modal landscapes.

Hybridizations are common: density-based runs produce a structural “skeleton,” followed by level-set refinement to sharpen boundaries and meet peak-stress targets. In CFD/thermal optimization, discrete adjoints in Siemens STAR-CCM+ and Ansys Fluent enable drag or pressure-drop minimization under tight constraints, and these adjoints increasingly integrate with structural adjoints for thermo-mechanical co-design. The result is a reliable, scalable core that can be wrapped with higher-level search or learning layers to handle objectives that violate smoothness assumptions.

Discrete and evolutionary exploration for combinatorial design

When design choices are inherently discrete—bolt patterns, rib counts, cutout libraries, off-the-shelf stock sizes—or when objectives are non-smooth, multi-objective genetic algorithms such as NSGA-II (led by Kalyanmoy Deb) remain go-to tools. They natively approximate Pareto fronts across conflicting goals (e.g., stiffness vs. mass vs. cost) without requiring convexity or differentiability. Rule-based and shape-grammar approaches complement these methods in domain-specific contexts: bracket families with catalog hole patterns, heat exchangers with parameterized fins, or housings with standardized bosses. Evolutionary search also acts as an outer loop around gradient-based cores, picking seed topologies, constraints, or process parameters while allowing the inner loop to fine-tune continuous fields.

- Use cases: discrete manufacturing choices, catalog-driven components, robustness to noisy simulations, and non-differentiable penalties (e.g., support removal labor).

- Practicalities: compute budgets are managed via population sizing, elitism, and early stopping; cloud scheduling and preemption-tolerant workflows (checkpointing) are essential.

Vendors operationalize these patterns differently: Altair’s Inspire/OptiStruct stack couples topology with design-of-experiments and evolutionary tools; Siemens and Dassault wrap GA/DOE in their optimization managers; and OEMs deploy in-house hybrids that mix SQP inner loops with GA outer loops for discrete plant constraints. The cultural lesson is that no single algorithm suffices—the viable stack is a portfolio, orchestrated by data and by the fidelity of available physics.

Surrogates and Bayesian optimization for sample-efficient search

Because high-fidelity FEA/CFD is expensive, surrogate modeling enters as a speed layer. Gaussian processes/Kriging offer uncertainty-aware regression; random forests and gradient-boosted trees capture interactions with durable generalization; neural surrogates scale to high-dimensional descriptors when embedded with physics-informed features. Bayesian optimization (BO) stitches these models to propose next experiments, balancing exploitation of known optima with exploration of uncertain regions. Active learning strategies target the Pareto front directly, while trust-region BO increases reliability by gating suggestions within validated neighborhoods. Multi-fidelity orchestration—e.g., cheap linear FEA or coarse CFD guiding sparse high-fidelity calls—improves sample efficiency.

- Common toolchains: Ansys optiSLang, Altair HyperStudy, and ESTECO modeFRONTIER integrate DOE, Kriging, and BO with enterprise solvers.

- Best practices: feature engineering from physics (e.g., non-dimensional groups), calibrated uncertainty estimates, and periodic ground-truth checks to prevent model drift.

In production, surrogates also act as run-time guards: before launching a thousand-core simulation, a lightweight model screens proposals against failure modes (excessive stress, unprintable features). Over time, these surrogates become corporate memory—capturing plant-specific constraints, supplier lead times, and empirical process windows—thereby personalizing generative exploration to the realities of each organization’s operations.

Neural generative models and differentiable stacks

Neural generative models provide priors on shape and topology. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) and GANs, trained on families of parts, can propose candidate geometries or latent vectors that warm-start optimization. Implicit representations—especially implicit signed distance fields—have been a breakthrough: DeepSDF (Park et al.) and Occupancy Networks (Mescheder et al.) encode continuous geometry that can be sampled at arbitrary resolution, booleaned robustly, and differentiated. These models align naturally with field-driven design and lattice parameterization, allowing generative systems to blend freeform skins with graded metamaterials.

Concurrently, differentiable physics and differentiable CAD are moving from papers to products. Automatic differentiation through meshing and contact remains hard, but end-to-end differentiability is emerging via analytic sensitivities for key operators and adjoint methods for PDEs. Research groups within Autodesk and Ansys, as well as startups, are prototyping kernels that propagate gradients from performance metrics back to sketch dimensions, loft parameters, and field coefficients—tightening the loop between engineering intent and geometry. The promise is a future where design teams steer continuous sliders and receive instant, provably consistent updates to both shape and process plans, with gradients guiding every link in the chain.

Manufacturability integrations and hybrid playbooks

To be useful, generative outputs must be buildable. For additive manufacturing, systems encode minimum wall thickness, overhang angles, support volume, powder removal paths, and material anisotropy; nTopology, Autodesk, and Siemens have rich libraries for lattices and gyroids with process-aware constraints. For subtractive processes, algorithms consider 2.5D milling directions, tool reach and deflection, parting lines for casting, and draft angles for injection molding; integrations with Altair Inspire Cast/PolyFoam and Dassault’s mold tools enable cost/defect-aware objectives. These constraints are not bolted on at the end; they are integrated into the optimization so that infeasible designs never surface.

- Hybrid playbook patterns:

- Run gradient topology optimization to produce seed skeletons; diversify with evolutionary search under cost/DFM penalties; refine with level-set for stress targets.

- Use neural shape priors to warm-start; fit CAD early to lock down critical interfaces; iterate with manufacturability-by-construction filters always on.

- Blend lightweight surrogates to screen proposals; then promoted candidates receive high-fidelity multiphysics simulation before release.

- Vendor flavors: Autodesk Fusion 360 Generative Design mixes multi-objective search with DFM filters and CAD reconstruction; PTC Creo Generative (via Frustum) leveraged voxelized analysis with smooth recon; Altair’s Inspire/OptiStruct blends topology with process simulations for casting and forming.

The unifying outcome is a portfolio pipeline where each algorithm plays to its strengths, and manufacturability constraints are native citizens of the objective—not afterthoughts.

Toolchains: data flow, kernels, and deployment patterns

Data model, representation, and meshing

Generative design begins with a rich data model. The design space, reference geometry, and keep-out/keep-in zones typically arrive from CAD as B-rep entities through kernels such as Parasolid, ACIS, or OpenCASCADE. Engineers specify materials (including composites and graded lattices), loads and boundary conditions, objectives (e.g., minimize compliance, pressure drop, or temperature), and constraints (stress, frequency, mass, cost, and manufacturing rules). During optimization, systems switch from boundary representations to field-based ones: voxel grids for density methods, tetrahedral meshes for FEA, level-sets for interface evolution, and implicit fields for lattices/TPMS. Lattice parameter fields—thickness, cell size, orientation—carry performance and process semantics while remaining compact.

- Inputs to structure:

- Geometry: B-rep solids/surfaces, interfaces to standard parts, and datum features to preserve.

- Physics setup: multi-load envelopes, thermal fluxes, fluid inlets/outlets, coupling maps.

- DFX policies: minimum feature sizes, overhang and draft targets, tool approach vectors, allowable stock.

- Meshing: TetGen and Gmsh are common open-source choices; commercial stacks leverage Simcenter and Abaqus meshing. Filters and radius controls enforce feature-size bounds and stabilize sensitivities.

Pre-processing also captures metadata essential to downstream continuity: PMI anchors for datums and tolerances; material specifications and lot traceability; and versioned configuration of solver settings. The payoff is a digital thread where any result can be reproduced and audited—an expectation as generative outputs become part of safety-critical products.

Solver–optimizer loop and PLM traceability

The inner loop ties solvers to optimizers with orchestration layers. Structural runs may leverage Altair OptiStruct, Ansys Mechanical, or Abaqus; thermal multiphysics may run in COMSOL; and organizations increasingly deploy in-house GPU FEM stacks to exploit CUDA and vendor-neutral APIs. CFD design uses adjoint engines in Siemens STAR-CCM+ or Ansys Fluent to optimize pressure drop, mixing, or aero loads. A study manager handles design-of-experiments, Pareto frontier curation, checkpointing for preemptible cloud nodes, and failure recovery.

- Traceability: PLM links in PTC Windchill, Dassault 3DEXPERIENCE, and Siemens Teamcenter record solver versions, mesh parameters, objective definitions, and reviewer sign-offs.

- Governance: access controls, model validation reports, and change notices form an audit trail compatible with regulated industries.

In this environment, reproducibility is a first-class requirement. Containerized environments pin compiler and library versions; license orchestration balances token pools across on-prem and cloud bursts; and data lineage ensures that when management revisits a decision, the exact computational pathway is recoverable. The result is not just speed—it is trustworthy speed that a quality organization can sign off on.

Post-processing and CAD round-trip

Optimization outputs are seldom release-ready. Voxelized fields become smooth parts through marching cubes or dual contouring; skeletonization may extract medial axes to rationalize truss-like forms. For manufacturing-grade geometry, systems fit NURBS or TSplines; Autodesk’s lineage with T-Splines popularized smooth, editable surfaces for organic shapes. The critical step is CAD reconstruction that respects engineering intent: preserving datum schemes, hole centers, offsets, and mating conditions. Feature creation (fillets, chamfers, blends) is not mere cosmetics; it addresses stress concentrations, tooling, and inspection feasibility.

- Format handoff:

- AM: STL/3MF carry tessellated solids, build parameters, and materials; lattice metadata may be embedded via extensions.

- MCAD: STEP AP242 and JT move semantic PMI and assembly context downstream.

- Tolerance: PMI and GD&T propagation ensures that generative changes do not break inspection/assembly. Offsetting and morphological operations allow robust clearance and allowance control.

Round-trip fidelity is a persistent bottleneck. Robust boolean operations, self-intersection prevention, and watertightness checks must be automatic, or else engineering teams spend cycles hand-fixing artifacts that algorithms should have avoided in the first place. The industry trend is tighter kernel/solver co-design so that what is optimal numerically is also stable geometrically.

Manufacturability verification, deployment, and visualization

Before release, designs undergo process-aware verification. For AM, distortion and warpage predictions, support placement, and residual stress mitigation are simulated in tools like Ansys Additive Suite, Siemens Simcenter 3D AM, and Autodesk Netfabb; build orientation and scan strategies are tuned to balance quality and throughput. For subtractive CAM, Siemens NX CAM, Mastercam, and Fusion CAM validate toolpath feasibility, fixturing, and cycle time; tool deflection and chatter risk can be folded into cost/performance trade-offs. Mechanical validation spans fatigue, buckling, thermal shock, NVH, and sometimes crash; Hexagon/MSC Nastran/Marc and Ansys/Dassault portfolios supply verification paths that mirror certification workflows in aerospace and medtech.

- Deployment: cloud bursts on AWS/Azure/GCP with containerized solvers, license pooling between on-prem and cloud, and token- or credit-based billing models.

- Visualization: real-time previews via NVIDIA Omniverse connectors; Unreal/Unity scenes for design reviews; and web viewers for enterprise access.

- Common design patterns (rather than case histories):

- Multi-load lightweighting with fatigue safety factors and frequency floors.

- Assembly consolidation with integrated cable routing and DFM checks.

- Thermal-fluid co-design of heat movers balancing pressure drop and manufacturable fin/lattice features.

The outcome is an end-to-end pipeline where feasibility and cost are evaluated alongside performance, and visualization is not just a pretty picture—it is a decision surface shared across engineering, manufacturing, and quality.

Conclusion: where hybrid generative design is heading

Convergence toward live, trustworthy exploration

The next frontier fuses differentiable CAD, adjoint multiphysics, and neural priors so that engineers can explore trade spaces in minutes, not days. Differentiability across geometry kernels, meshing, and solvers allows gradients to propagate cleanly from performance to parameters; adjoints keep costs nearly constant as variable counts explode; neural priors propose promising regions of the space that respect learned shape grammars and process constraints. Hardware acceleration (GPUs and emerging AI accelerators) and smarter caching/checkpointing compress iteration loops; cloud-native orchestration spreads workloads elastically without burying teams in IT chores. The point is not to remove humans but to amplify them—surfacing high-quality options quickly, with explainable sensitivity maps and constraint diagnostics that build trust. Expect platform providers to co-design geometry and solver kernels so that what is rapid is also robust, enabling “live” Pareto navigation inside mainstream CAD environments.

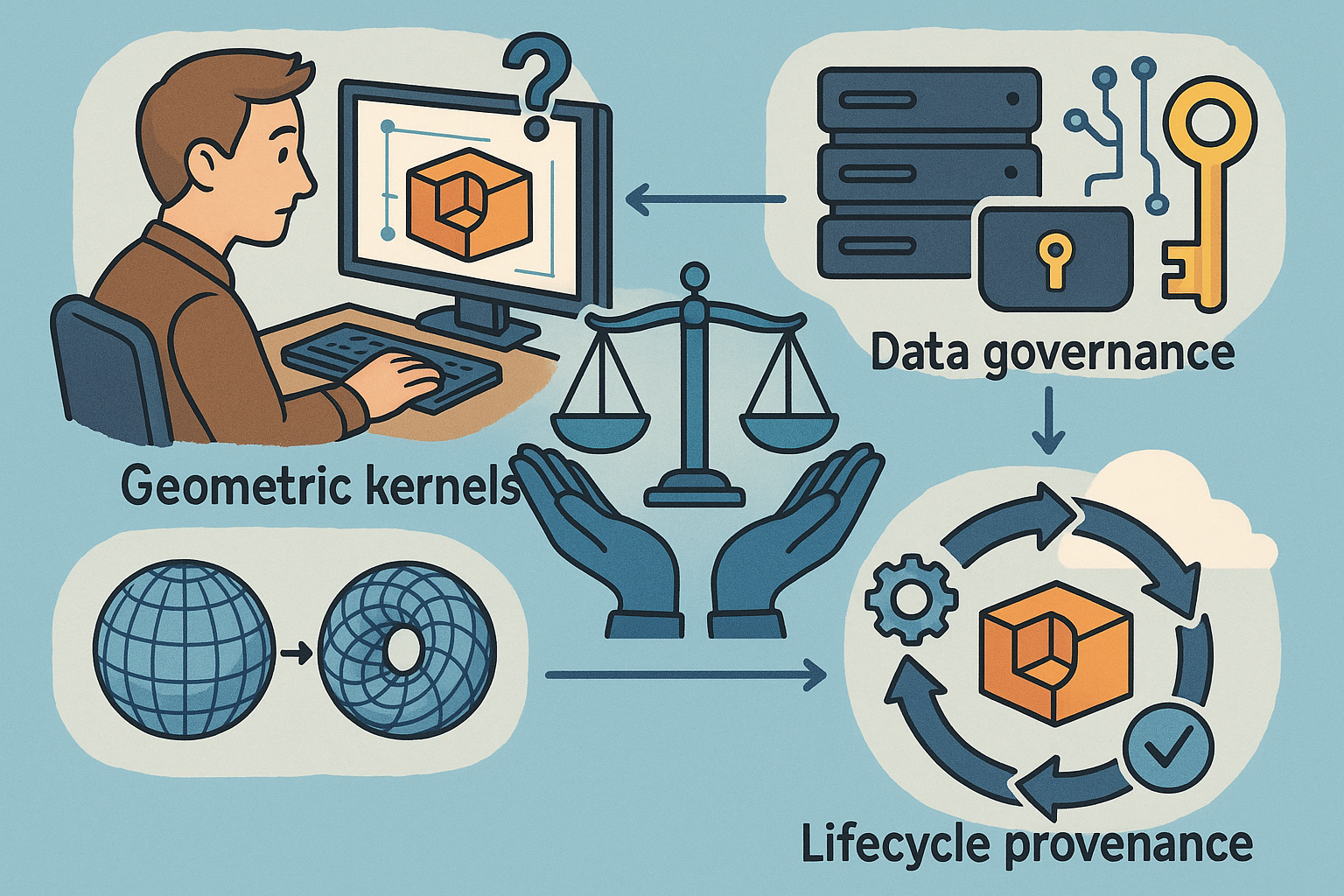

Reliability, reconstruction, and standards-based continuity

Reliability remains the gating factor between demos and production. Robust CAD reconstruction, watertightness, and defect-free booleans must be boringly reliable. Standards-based PMI carryover—GD&T symbols, datum schemes, edge break specs—prevents expensive rework in inspection and assembly. PLM-native provenance ensures every generative decision is auditable: what solver version, which mesh parameters, who approved the constraint changes, and why a candidate was selected. Geometry repair must move from a hero skill to an automated, statistically reliable service embedded in the kernel. Expect mature platforms to fuse kernel operations (offset, fillet, shell, lattice instantiation) with solver-aware guards, so the design space sampled by optimization is inherently clean. This is the path to scalable model-based definition (MBD) where governance teams can sign off on machine-authored content without fear of hidden landmines.

From constraints to capabilities: manufacturability-by-construction, governance, and talent

Embedding process physics into objectives turns manufacturability from a late-stage constraint into a first-class capability. For AM, that means optimization that anticipates distortion, residual stress, and microstructure evolution; for subtractive, reachability, deflection, and tool wear; for composites, layup directionality and cure kinetics. As these capabilities mature, governance must keep pace. PLM-native provenance, model risk management, and audit trails will be essential as machine-authored geometry enters regulated lifecycles. Organizations will invest in cross-skilled teams that span optimization theory, CAE, CAM, materials, and data science—and they will demand open APIs/SDKs so that internal know-how can shape the engine. Watch Autodesk, PTC, Siemens, Dassault Systèmes, Altair, Ansys, nTopology, and Carbon: they are well-positioned to drive the co-evolution of kernels and solvers, with startups pushing on differentiable stacks and implicit modeling.

- North-star trajectory:

- Co-design of geometry, material, and process parameters, validated continuously against digital twins of both part and factory.

- Simulation as a creative partner—surfacing options, diagnosing trade-offs, and explaining sensitivities—rather than a late-stage gatekeeper.

- Human-in-the-loop workflows with transparent metrics, standards alignment, and automatic documentation that satisfies quality audits.

When these pieces click, generative systems will feel less like black boxes and more like collaborative colleagues—ones that negotiate performance, cost, and manufacturability with fluency, and deliver shapes that are not merely optimal on paper but eminently buildable in the real world.

Also in Design News

Design Software History: CAD Ethics and Data Governance: From Geometric Kernels to Lifecycle Provenance

February 27, 2026 13 min read

Read More

Real-Time Collaboration Metrics for Design: Taxonomy, Instrumentation, and Governance

February 27, 2026 12 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Redshift SSS in Cinema 4D — Scale, Radius & Lighting

February 27, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …