Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History: From Usenet to Cloud: How Forums, Tutorials, and Open Libraries Transformed CAD Practice

February 07, 2026 13 min read

Origins and early communities: from Usenet to vendor forums

Pre-web roots

The earliest communities that shaped computer-aided design did not convene on glossy vendor portals; they took root in plain-text Usenet’s comp.cad.* newsgroups, role-modeled by adjacent technical hierarchies such as comp.graphics and comp.lang.*. In those channels, engineers, drafters, and researchers asked blunt questions about coordinate systems, spline control points, ACIS versus Parasolid quirks, printer drivers, and DXF oddities—and received answers from peers who often signed their posts with institutional lineages like national labs or university CAD/CAM centers. Mailing lists, from faculty-run design computation circles to fledgling SIGs around AutoCAD and Pro/ENGINEER, nurtured etiquette that would later define broader CAD culture: post sample files, include your system configuration, annotate macros, and report version numbers precisely. Parallel to this, dial-up BBS culture let users swap AutoLISP snippets, PCX/TIFF drivers, and PostScript utilities, while university lab lists seeded repositories of macros and sample parametric models that were copied between campuses and small consultancies. A typical thread might share an AutoLISP routine to batch-purge layers, followed by a Pro/ENGINEER trail file trick, and finally a Pascal utility for converting IGES entity types—cross-pollination that prefigured modern multi-tool workflows.

Those channels normalized the idea that CAD practice is an evolving conversation: if you solved a tangency constraint bug on HP-UX, you posted the patch; if your spline fit misbehaved at join tolerances, you shared the control polygon and a workaround. In that pre-web moment, two practices emerged that would endure:

- Rapid peer triage built on reproducible test files and minimal examples.

- Open sharing of code snippets, macros, and file converters as communal capital, not proprietary secrets.

User groups formalize the grassroots

As graphical workstations gave way to mainstream Windows CAD and the installed base exploded, informal collectives professionalized. The North American Autodesk User Group (NAAUG) became AUGI (Autodesk User Group International), a model for vendor-endorsed yet community-run knowledge exchange. AUGI’s magazines, wish lists, and chapter meetings crystallized habits from Usenet—post reproducible models; document AutoLISP/VBA workflows—into predictable programs. Meanwhile, SOLIDWORKS, founded by Jon Hirschtick and powered by the Parasolid kernel, catalyzed local meetups that eventually coalesced into the SWUGN (SOLIDWORKS User Group Network). Champions like Richard Doyle organized chapters, roadshows, and show-and-tell nights where attendees unpacked loft failures, mating strategies, and PDM nightmares with practical candor.

These groups established durable rituals that spread across the ecosystem:

- Vendor-proximate influence: annual “top ten” wish lists became product signals that teams at Autodesk, Dassault Systèmes, PTC, and Siemens monitored closely.

- Peer-to-peer training: sessions on configurations, design tables, and feature patterns frequently outpaced official documentation in clarity and speed.

- Community-maintained code: curated AutoLISP vaults, VBA macros, and later Python tools for FreeCAD and Rhino became quasi-standards.

Web 1.0 era forums consolidate expertise

The first generation of web forums concentrated dispersed expertise into durable hubs. On the independent side, Eng-Tips (Engineering.com) aggregated niche subforums for AutoCAD, Pro/ENGINEER, CATIA, and later SOLIDWORKS, with a culture of engineering-grade answers and cross-disciplinary reach into FEA, CFD, and machining. CNCzone blended CAM talk with controller hacking and fixture design, while The Swamp and CADTutor became go-to destinations for AutoLISP, scripts, and visualization tips. Rhino’s original NNTP newsgroup, later migrated into McNeel Discourse, exemplified a developer-accessible ethos where Robert McNeel & Associates staff and power users iterated on NURBS and Grasshopper concepts out in the open. Vendors followed suit with centralized portals: the Autodesk Discussion Groups (later Autodesk Community), the SOLIDWORKS Forums, and communities around PTC (Pro/ENGINEER/Creo) and UGS/Siemens NX welcomed direct staff engagement, knowledge-base crosslinks, and downloadable samples.

This consolidation mattered for three reasons:

- Continuity: threads persisted, forming an institutional memory of kernel corner cases (e.g., Parasolid sew/knit behavior, ACIS boolean robustness) and platform-specific gotchas.

- Discoverability: search engines began to privilege forum posts with code blocks, version tags, and attachments, making answers findable within minutes.

- Participation design: voting, accepted answers, and file upload policies codified best practices from Usenet into structured support models.

Independent media and aggregators amplify reach

Beyond forums, independent editors and curators shaped the conversation by connecting product changes to business and kernel politics. Ralph Grabowski’s WorldCAD Access demystified DWG politics, the realities of ACIS licensing, and the microeconomics of low-cost CAD, while publishing tool-by-tool analyses that traced how features evolved across releases. DEVELOP3D, led by Al Dean and Martyn Day, fused journalist-grade product reviews with manufacturing context, elevating topics like topology optimization and additive-driven design. SolidSmack, under Josh Mings, amplified emergent workflows with a design-and-fabrication sensibility, and TenLinks, founded by Roopinder Tara, functioned as an early aggregator indexing tutorials, press, and opinion. This constellation provided a metastructure: practitioners could track kernel migrations (e.g., CGM in CATIA/3DEXPERIENCE, Parasolid in SOLIDWORKS and NX), grasp corporate integrations, and anticipate compatibility ripples across supply chains.

Crucially, independent voices cultivated healthy skepticism:

- They explained when a “new” feature was a UI shell over long-standing kernel primitives.

- They archived vendor commitments and contrasted them with lived forum reports.

- They gave airtime to open-source efforts like FreeCAD and OpenSCAD, validating alternative toolchains.

Cultural legacies

The most durable legacies from these early communities are cultural. First, the norm of openly posting models, macros, and benchmarks—from AutoLISP block tools and VBA batch processors to Python scripts for FreeCAD and Rhino—hardened the expectation that solutions are public goods. Second, the “answer in minutes” ethos, reinforced by Eng-Tips and vendor forums alike, forced vendors to rethink support: public triage with reproducible files often resolved issues faster than tickets, and patterns visible across threads nudged product managers to prioritize highly recurrent bugs (fillet collapses, STEP AP214 vs. AP242 quirks, sketch solver instability). Third, the habit of posting performance benchmarks—regen times, import tolerance sweeps, mesher stability under parameter sweeps—encouraged empirical comparison, not marketing narratives.

These norms had technical spillovers:

- File minimalism: users learned to craft tiny, surgical test models that isolate kernel behavior.

- Scriptability: grassroots sharing lifted expectations that every modern CAD should expose robust APIs for parametric automation.

- Cross-tool literacy: operators became fluent in translating concepts between AutoCAD, SOLIDWORKS, Creo, NX, and Rhino, eroding tool silos.

Tutorials and the learning economy: blogs, videos, MOOCs, and wikis

The blog era

As RSS readers bloomed, practitioner-authored blogs turned incremental product changes into digestible, situated knowledge. Deelip Menezes chronicled CAD politics with unusual clarity: kernel licensing battles, API gatekeeping, and DWG alliances that shaped interoperability far more than splashy UI refreshes. Ralph Grabowski continued his deep, tool-by-tool coverage, annotating not just what a feature did, but what geometry engine behavior it implied. Niche authors documented how to bend parametrics to organizational reality: versioning patterns with PDM vaults, master model strategies, and robust surfacing practices for Class-A adjacent work. The blog format—timestamped, linkable, amenable to code and screenshot snippets—functioned as a living archive where comments became a low-latency peer review cycle.

Three practical shifts flowed from this era:

- Practitioner authority: posts from veteran modelers carried the gravitas of battle-tested patterns, not theoretical recipes.

- Kernel literacy: readers learned to recognize when a failure was a sketch constraint flaw, a feature order problem, or a Parasolid/ACIS limitation, sharpening bug reports.

- Community memory: evergreen posts (e.g., “how to diagnose fillet rollovers” or “IGES trimming tolerance pitfalls”) became canonical references that forums linked for years.

Video-native learning

As bandwidth and screen recording matured, video became the dominant vernacular for practical skills. YouTube channels like Lars Christensen demystified Fusion 360 with a hands-on, “sketch, extrude, inspect” cadence that mirrored daily practice, while NYC CNC bridged CAD to CAM, showing how toolpath strategy and fixturing interlock with model intent. Crucially, long-form streams of failures, do-overs, and shop-floor realities replaced polished highlight reels; the medium normalized learning through visible iteration. Vendors amplified this by publishing vast session libraries from Autodesk University, 3DEXPERIENCE World, PTC LiveWorx, and Siemens Realize Live, turning conferences into permanent courseware.

Video-native pedagogy reshaped expectations:

- “Show the clicks”: viewers wanted explicit sequences, not abstract prompts—mirroring the traceability of trail files and feature trees.

- Context-first instruction: instructors framed modeling around manufacturing constraints (tool reach, draft, GD&T) and data management, not just geometry.

- Replayable micro-lessons: the 5–12 minute segment became the atom of learning, supplanting bulky manuals.

Structured platforms

The rise of structured learning platforms formalized curriculum, assessment, and credentialing. Lynda.com/LinkedIn Learning standardized beginner-to-advanced sequences for AutoCAD, SOLIDWORKS, and Rhino, pairing videos with downloadable exercise files. Coursera and edX bootstrapped university-linked series on design for manufacturing, generative algorithms, and simulation, giving learners a scaffolded path into FEA/CFD or architectural computation. Certified partner trainings from Dassault Systèmes, PTC, Autodesk, and Siemens synchronized content with exam blueprints, raising the currency of badges in hiring and vendor ecosystems. Meanwhile, Onshape’s Learning Center stitched platform-native interactivity—embedded exercises, immediate feedback—into a born-cloud experience, while public Onshape Documents made tutorials discoverable and remixable, letting learners fork models and inspect version histories to see modeling decisions unfold.

This structured layer delivered:

- Consistency: common vocabularies and mental models reduced friction as teams onboarded across geographies and time zones.

- Assessment with artifacts: quizzes and capstones produced models that doubled as portfolios, tightening the feedback loop to hiring.

- Data-driven iteration: platforms instrumented drop-off points, enabling creators to refine modules that routinely confused learners.

Community documentation

Open communities built documentation by the people, for the people. FreeCAD’s wiki and forum-led guides evolve in step with workbenches like Part Design, Path, and FEM, while GitHub issues tether docs to source, making “docs-as-code” more than a slogan. OpenSCAD’s community examples showcase a pure parametric text-based approach, illuminating how constructive geometry composes from operators and modules. In AEC, the Grasshopper3D forums and McNeel’s developer guides expose geometry kernels, RhinoCommon, and Rhinopython at a level that empowers customization; Food4Rhino turns plugin discovery into a learning pathway, where reading someone’s definition is itself instruction. BIM communities like RevitCity and BIMobject established the scale and metadata depth needed for architectural families, from materials and level-of-detail rules to MEP connectors.

These ecosystems share principles:

- Executable documentation: examples and definitions run as-is, shrinking the gap between reading and doing.

- Community maintainership: moderators and maintainers are recognized as stewards, not gatekeepers, encouraging high-signal contributions.

- Traceability: changelogs and forum links preserve the genealogy of a tip or definition.

Effects on practice

The cumulative effect of blogs, videos, structured platforms, and wikis has been a compression of learning curves and a reconfiguration of expertise. Career switchers and students enter the field through micro-lessons that demonstrate complete, real-world outcomes—designing an enclosure with draft and snap fits, or creating a parametric bracket tolerant to print shrink—rather than abstract toy examples. Since these lessons include downloads and versioned models, they function as de facto documentation that evolves in a way closed help systems struggle to match. Organizations benefit as internal onboarding shifts from “read the manual” to “follow this curated playlist and fork this repo,” reducing time-to-productivity and uplifting baseline quality.

Practice also becomes more transparent:

- Debuggability improves because learners adopt the norm of isolating minimal failing models and sharing them with peers.

- Cross-disciplinary literacy grows as CAM and simulation are woven into modeling pedagogy.

- Community feedback scales: view counts, comments, and forks quantify what works, guiding both educators and vendors.

Open libraries and shared assets: models, code, and parametric parts

Model-sharing at scale

Mass-scale model libraries redefined what “starting from scratch” means. GrabCAD, founded by Hardi Meybaum and Indrek Narusk and later acquired by Stratasys, popularized open repositories of assemblies, concept designs, and tooling, while Workbench experimented with collaborative versioning before cloud CAD was mainstream. Thingiverse, launched by MakerBot under Bre Pettis, with Adam Mayer and Zach Smith, catalyzed consumer additive manufacturing by turning STL culture into a social feed of remixes and upgrades; MyMiniFactory and Prusa’s Printables evolved content moderation and quality vetting for the 3D-printing wave. On the professional side, 3D ContentCentral (Dassault Systèmes), TraceParts, and CADENAS PARTcommunity normalized manufacturer-certified parts and dimensionally accurate hardware libraries, merging procurement and design-in with a few clicks.

Two dynamics transformed workflows:

- Time-to-first-geometry shrank as engineers dropped in vendor-native fasteners, actuators, and pneumatics that carried proper metadata and mates.

- Idea remixing flourished: designers forked parametric concepts—robot grippers, ergonomic handles—and adapted them, rather than modeling de novo.

Parametric and scriptable assets

Beyond static models, communities embraced parametric and code-first assets that travel across contexts. OpenSCAD libraries encode design intent as composable modules; CadQuery projects expose Pythonic, readable solids; and FreeCAD’s GitHub-hosted workbenches demonstrate how specialized domains—sheet metal, FEM, CAM—grow in the open. Grasshopper definitions shared on Food4Rhino make algorithmic patterns—panelizations, space frames, daylighting analyses—extensible across AEC practices. BIM platforms adopted similar logic with RevitCity and BIMobject foregrounding parameterized families, type catalogs, and MEP metadata at scale.

The power of scriptable assets is threefold:

- Remixability with guarantees: adjusting a module or slider ripples changes consistently, preserving constraints in ways STL remixes cannot.

- Inspection and governance: parameters, units, and defaults are visible; version control ties them to issues and reviews.

- Automation adjacency: code-centric assets integrate with CI, validators, and batch generators, enabling design-at-scale patterns (e.g., auto-generating variant brackets across material sets).

Quality, provenance, and licensing

As open libraries grew, questions of trust and legality followed. Communities evolved QA signals—comments that surface fit-up successes and failures, star/fork counts as crude proxies for quality, and version histories that map the genealogy of a part. Some platforms added printability checks, unit detection, and “verified” badges, but much of the practical assurance remains social: has a part been remixed widely? Do power users endorse it? Meanwhile, licensing frictions remain endemic. Creative Commons schemes coexist uneasily with proprietary EULAs; DMCA takedowns occur when branded models or weapon-adjacent items surface; attribution and derivative-use ambiguity regularly confounds professionals who need clean IP chains. Beyond legalities lies a semantic gap: geometry moves, but PMI, GD&T, tolerance stacks, surface finish, and material-process intent are inconsistently preserved, especially when workflows devolve to mesh exchanges.

Addressing these gaps requires combined approaches:

- Provenance tooling: signing, watermarking, and SBOM-style manifests to track model lineage and parameter changes.

- Richer containers: pushing STEP AP242 and JT with PMI, or vendor-neutral recipes that carry mates, FT&A, and simulation-ready metadata.

- Machine-readable licenses: embedding SPDX-like identifiers and policy-aware gates into repositories and PLM systems.

Industry feedback loops

Open sharing has tightened the loop between field practice and product direction. Vendors mine aggregate trends—recurrent fillet failures on thin-walled parts, STEP import quirks from competitor exports, sketch performance regressions—to prioritize backlogs with evidence beyond anecdote. Part suppliers have pivoted marketing toward CAD-native assets: instead of glossy PDFs, they offer parametric configurators, native downloads, and embedded mates, effectively becoming co-authors of your assembly’s feature tree. Meanwhile, toolmakers watch plugin ecosystems (Grasshopper on Food4Rhino, FreeCAD workbenches, Fusion extensions) to identify white spaces worth productizing natively.

Three flywheels emerge:

- Adoption through assets: when certified models and macros solve real work, platform selection becomes less about UI and more about ecosystem gravity.

- Quality through visibility: public failures, repro files, and remixes pressure vendors to fix brittle algorithms and harden importers.

- Education through practice: libraries double as tutorials, and tutorials yield libraries—collapsing the distance between learning and doing.

Conclusion

Community-driven transformation and its leverage

Across four decades, community-driven resources have transformed CAD from a tool-centric purchase into a network-centric practice. Forums and user groups slashed support cycles by normalizing reproducible test files and collective debugging, while surfacing edge cases that only emerge in production-scale assemblies and shop-floor handoffs. Tutorials, videos, MOOCs, and wikis compressed learning curves, making advanced workflows—robust surfacing, PDM discipline, simulation setup—achievable by newcomers in weeks rather than years. Open libraries reframed modeling as a remix culture: engineers start from proven patterns, drop in certified suppliers’ parts, and wire parametric definitions to automate families of variants, boosting design velocity without sacrificing intent.

Yet the transformation remains uneven. Trust and quality signals for downloadable models are still too social and too coarse for safety-critical parts; standardized provenance and validation trails are the next frontier. Licensing remains murky in mixed open/proprietary pipelines, clouding attribution and derivative rights just when reuse is most valuable. And the industry still struggles to preserve semantics—tolerances, PMI, manufacturing constraints—alongside geometry; without those, shared models risk becoming beautiful but ambiguous shapes. The leverage point is clear: vendors and educators who integrate community-native practices—docs-as-code, sample repos, transparent roadmaps—into product surfaces will set the bar for reliability, velocity, and trust.

Challenges, strategy, and the road ahead

Strategically, the path forward hinges on treating community as infrastructure. Vendors should elevate forums, wikis, and sample libraries to the same design rigor as modeling features, with telemetry-informed roadmaps and maintainers recognized as co-authors of product direction. Investment in metadata standards, provenance tooling, and automated validators can upgrade quality signals from star counts to cryptographically signed, machine-checked artifacts. Educators can align curricula with community assets, teaching not only modeling but also scripting, version control, and stewardship—skills that future-proof careers. Looking ahead, AI-assisted search, summarization, and model linting will raise baseline quality, while reputation graphs and structured ontologies will underwrite trustworthy sharing. Watermarking and signing can codify lineage, and CI-like pipelines can test models for unit consistency, tolerance propagation, and manufacturability before publication.

The next wave of CAD literacy will blend hands-on modeling with code fluency and community contribution. Professionals will be expected to publish minimal repros, annotate parameters with intent, embed licenses, and wire validators into release flows. In that world, advantage accrues to teams that can harness the ecosystem: for discovery, for acceleration, and for continuous improvement driven by public evidence. The promise is compelling: a field where design intent travels as predictably as geometry, learning compounds through shared artifacts, and the line between product and community fades—replaced by a living system that designs, teaches, and improves itself.

Also in Design News

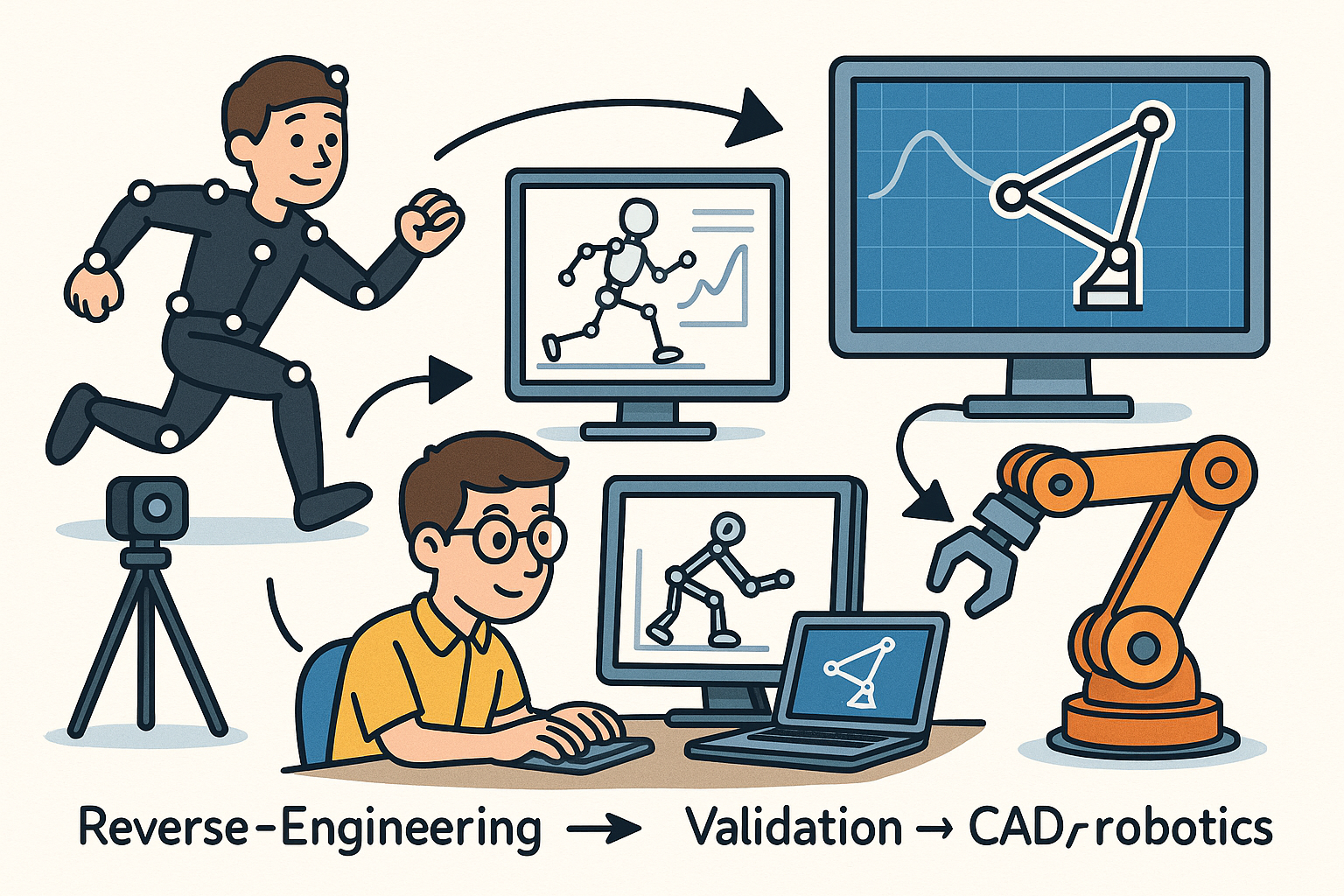

Reverse-Engineering Mechanisms from Motion Capture: Kinematic Identification, Validation, and CAD/Robotics Export

February 07, 2026 12 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Guide-First Hair Grooming Workflow for Cinema 4D

February 07, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …