Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

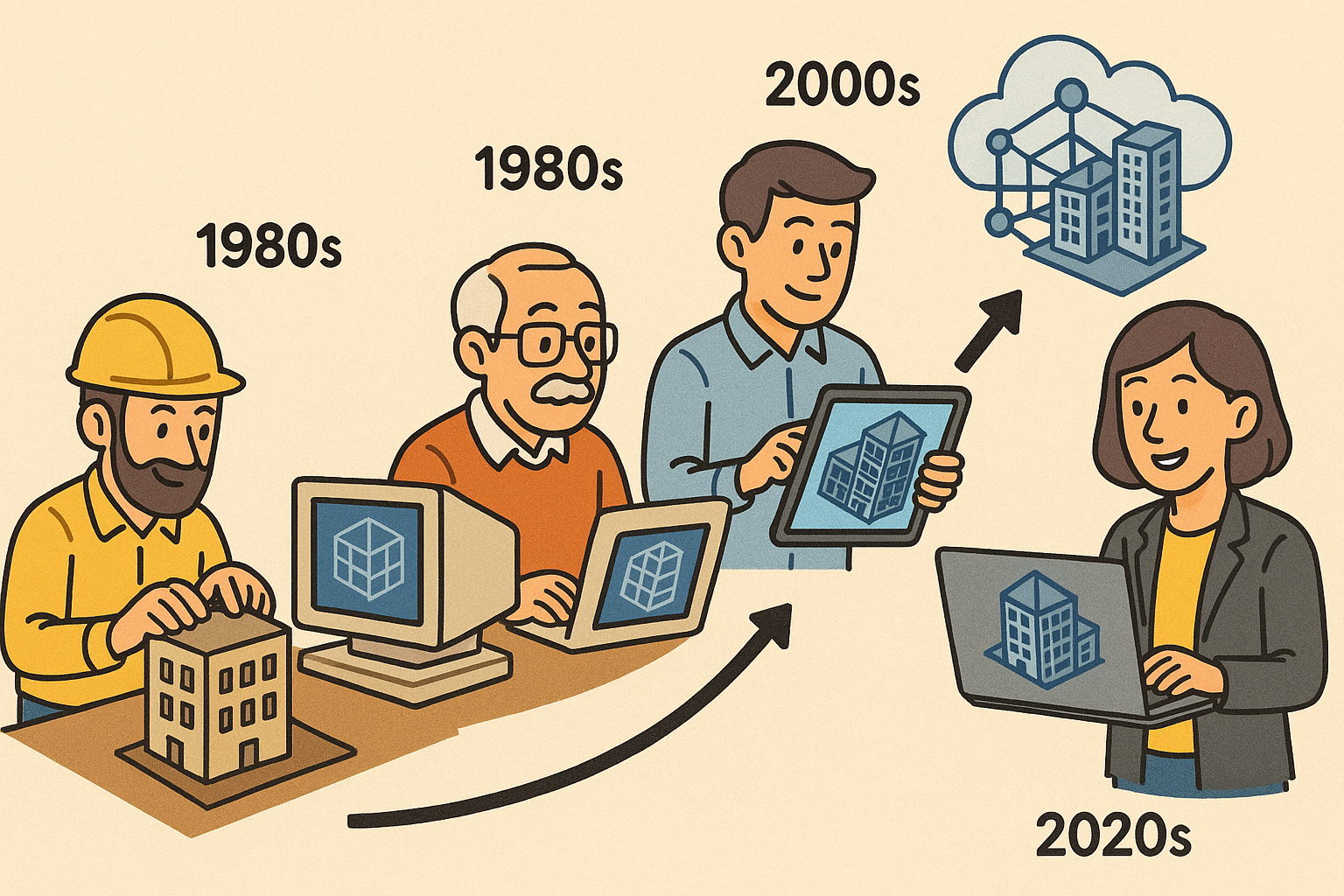

Design Software History: From Object-Based Models to Digital Twins: The Evolution of BIM, Standards, and Computable Project Workflows (1970s–2020s)

December 03, 2025 12 min read

Origins: Early Building Data Models and Proto-BIM (1970s–1990s)

Foundational research

The roots of today’s object-based building information modeling trace directly to the research of Charles M. Eastman at Carnegie Mellon and Georgia Tech, whose Building Description System (BDS, 1974) and later GLIDE showed that a building could be represented as a computable assembly of semantically rich parts. BDS organized walls, slabs, openings, and spaces as discrete objects with attributes and explicit relationships—voids cutting solids, spaces bounded by surfaces, and constraints that could be checked or queried. Crucially, Eastman argued for a queryable repository of building elements rather than mere drawings, anticipating schedules, quantities, and consistency checks generated from a single source of truth. GLIDE pushed these ideas toward interactive editing and the idea of persistent object identities that survive across edits and views.

In parallel, the broader product data community was coalescing around ISO 10303 STEP and its schema language EXPRESS, while the AEC domain explored reference models like Bo-Christer Björk’s GARM (General AEC Reference Model). These efforts planted the seed for a neutral, schema-first mindset: define entities, attributes, and relationships in a platform-independent form so models can be validated and exchanged. From early topological kernels to property graphs, the emphasis shifted from geometry alone to semantics—what is a wall, how does a door relate to its host, and which constraints govern them? That shift, born in academic labs, set a durable conceptual foundation: building data models should be explicit, verifiable, and portable across tools and lifecycle stages.

Commercial forerunners

By the early 1980s, commercial pioneers began translating research into production software. GMW Computers’ RUCAPS offered 2.5D/3D project coordination and was famously used on Heathrow Terminal 3, signaling that multi-stakeholder modeling could help orchestrate complex building programs. While RUCAPS predated modern parametrics, its layered representations, building-scale scope, and drawing extraction hinted at integrated delivery. Jonathan Ingram’s Sonata (1986) and later Reflex (1992) advanced the concept of parametric components and constraints spanning building systems, a pivotal step from drafting toward behavior-driven modeling. Ingram’s ideas, and Reflex’s subsequent acquisition by PTC, echoed across the industry, influencing parametric thinking that would later shape mainstream BIM tools.

In 1987, Gábor Bojár’s Graphisoft released ArchiCAD, branding its approach as the “Virtual Building.” Walls, doors, and windows had parameters and understood their host relationships; sections and schedules were computed from the model rather than redrawn. Early Teamwork features, and later WAN-optimized syncing via the “Delta Server,” demonstrated that distributed collaboration was not only possible but practical. Together, these forerunners made three ideas tangible: model once and generate many deliverables; encode design intent as constraints and object semantics; and support collaboration within a single digital environment that understands how building elements interrelate.

Standards and communities emerge

In 1994, the International Alliance for Interoperability (IAI)—later buildingSMART—formed to institutionalize the exchange of object-based building data. The first Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) specification appeared in 1997, focusing on formalizing object semantics (e.g., IfcWall, IfcDoor), relationships (Aggregation, Containment, Voiding), and typed properties in a vendor-neutral schema. This was an explicit bridge between the AEC world and the data-modeling principles of STEP/EXPRESS, and it catalyzed a community that treated interoperability as an engineering problem, not a marketing slogan. The late 1990s saw active experimentation with model view definitions, schema validation, and early guidance on practical exchanges.

At the same time, language was shifting. The phrase “product models” gradually gave way to Building Information Modeling (BIM), a term popularized in the early 2000s by Jerry Laiserin, who used it to differentiate object-based, information-rich workflows from CAD-centric drafting. The community coalesced around the idea that BIM was both a technology stack and a process change—more akin to a shared database than a set of disconnected files. By the end of the 1990s, the path was clear: research prototypes had proven object-based modeling; early commercial systems had made it useful; and standards bodies had begun the long work of making the ecosystem interoperable at scale.

The BIM Era Arrives: Parametric Platforms and Coordinated Delivery (2000s–mid‑2010s)

Platform consolidation and parametrics

The early 2000s delivered the first broadly adopted, fully parametric BIM platforms. Revit, founded by Leonid Raiz and Irwin Jungreis (both alumni of PTC’s parametric CAD world) and acquired by Autodesk in 2002, embedded constraints, dimensions, and relationships directly in building elements and their hosting logic. Its programmable Family Editor enabled content libraries with intelligence—doors that know how to cut walls, curtain panels that scale by rules, MEP fittings that maintain connectivity. The platform’s associative change propagation across plans, sections, and schedules actualized the “single source of truth” for drawing production and quantity extraction.

Meanwhile, ArchiCAD deepened its collaboration DNA through BIM Server/BIMcloud, and the Nemetschek ecosystem matured around Graphisoft, Allplan, and Vectorworks. Bentley Systems leveraged the MicroStation platform for building design via AECOsim Building Designer (today OpenBuildings Designer), integrating with bentley-native structural and plant tools. For heavy structural and fabrication detail, Trimble’s Tekla Structures became a staple for steel and reinforced concrete, bridging from design intent to shop-detail level information. Together, these platforms normalized parametric, view-coherent, multi-discipline modeling, while leaving room for domain-specialized tools to plug into coordinated delivery.

Coordination, 4D/5D, and constructability

As projects embraced multi-author federation, the market pivoted to model coordination and constructability. Navisworks (acquired by Autodesk in 2007) became the de facto model aggregator and clash detection engine on large jobs, while Solibri emphasized rule-based model checking and data quality. Tekla BIMsight expanded coordination workflows within structural supply chains. The emergence of 4D scheduling and 5D cost linked models to time and money. Vico Software (later acquired by Trimble in 2012) pioneered construction-caliber quantity takeoff, location-based management, and schedule integration; Synchro (acquired by Bentley in 2018) popularized robust 4D workflows across civil and building sectors, integrating with P6 and other schedulers.

Practitioners realized that a well-structured model could support more than drawing production—it could drive work packaging, logistics, and risk reduction. Effective coordination workflows typically involved:

- Federating discipline and trade models into a shared space for detections and viewpoints.

- Tracking issues and responsibilities across platforms with BCF linked back to source models.

- Using 4D to simulate site sequencing and identify staging conflicts early.

- Leveraging 5D to tie quantities and assemblies to cost codes and procurement cycles.

Standards and mandates scale adoption

Open standards matured into practical levers for adoption. IFC2x3 became the de facto exchange baseline for architecture, structure, and MEP over the 2000s, enabling cross-vendor federation and data handoffs. The US Army Corps of Engineers, led by Bill East, systematized operations-ready asset data via COBie, giving owners a spreadsheet-friendly, model-derived bridge to CMMS/CAFM. BCF standardized issue exchange across coordination tools, further decoupling process from platform. Government leadership amplified these effects: the US GSA introduced BIM requirements starting in 2003; the UK’s BIM Level 2 mandate in 2016 drove structured deliverables and CDE workflows; Nordic public clients like Statsbygg and Senate Properties led early with IFC-based procurement; Singapore’s BCA advanced model-based e-submissions.

These policies incentivized Common Data Environments (CDEs) such as Bentley ProjectWise and Autodesk BIM 360 to support controlled workflows, transmittals, and audit trails. The result was a process overlay—naming conventions, approval gates, and model exchanges—formalized around open schemas and clear responsibilities. As deliverables gained structure, templates and employer information requirements codified “what good looks like,” pushing BIM beyond a modeling technique into an organizational capability directly tied to procurement and risk management.

Analysis and sustainability integrations

The BIM core also tapped into analysis engines, closing loops between design, simulation, and documentation. Energy and daylighting tools—EnergyPlus, IES VE, and Autodesk’s Ecotect—linked geometry, materials, and weather data to inform envelope and system decisions early. With parametric modeling, teams could explore options and propagate changes across drawings and schedules, accelerating feedback. The notion of model-connected simulation extended to ventilation effectiveness, thermal comfort, and solar control, bringing performance discussions into mainstream workflows rather than late-stage validation.

Key patterns emerged:

- Use BIM geometry as a shared “spatial truth,” then map material assemblies and gains/losses for energy models.

- Iterate rapidly: parametric changes ripple through both documentation and analysis, tightening the learn–decide loop.

- Store assumptions: embed key performance attributes as properties so they travel with the model into later phases.

Convergence: Open Workflows, Reality Capture, and Computable Projects (mid‑2010s–2020s)

BIM meets GIS and infrastructure; reality meshes enter the picture

From the mid‑2010s, BIM converged with GIS and infrastructure modeling. The Esri–Autodesk partnership aligned ArcGIS and Revit/Civil 3D contexts, while open city models like CityGML provided urban-scale semantics. On the standards front, buildingSMART’s InfraRoom accelerated IFC4/4.3 for roads, rail, and bridges, taking civil assets from alignment geometry to domain entities (e.g., IfcBridge, IfcAlignment). In parallel, reality meshes created from photogrammetry and LiDAR—popularized by tools like Bentley’s ContextCapture—offered richly textured, geolocated context for design and coordination, blurring boundaries between surveyed reality and designed intent.

Reality capture matured into closed loops: terrestrial and mobile scanners from Leica Geosystems, FARO, and Trimble generated massive point clouds (E57, LAS/LAZ), feeding scan-to-BIM pipelines and construction verification. Teams compared design tolerances to as-built captures for dimensional QA and progress tracking. As SLAM and drone photogrammetry extended coverage, the federated project context became computable from city to bolt. The practical outcome was a workflow in which site conditions are continuously measured, models are constantly reconciled with reality, and context-aware design decisions are made earlier and with higher confidence.

Computational design, generative rules, and open extensibility

With models becoming data-rich, computational design rose to prominence. Rhino/Grasshopper empowered rule-based geometry and performance-driven form finding, and Rhino.Inside.Revit created an in-process bridge that combined Revit’s parametric assemblies with Rhino’s flexible NURBS and meshing. Autodesk’s Dynamo embedded visual programming in the BIM environment, letting teams automate repetitive tasks, enforce naming rules, and prototype custom logic for model QA. On the checking side, Solibri rulesets and emerging code-checking workflows operationalized requirements as executable constraints, forming the nucleus of computable compliance.

Open tooling flourished. IfcOpenShell provided programmatic access to IFC in Python and C++; BlenderBIM brought authoring and auditing to a free, open-source environment. The formalization of MVD (Model View Definitions) and IDM (Information Delivery Manual) clarified what information must be exchanged, by whom, and when. ISO 19650 codified information management processes on top of CDEs, while BCF 2.x improved cross-tool issue workflows. Together, these tools allowed firms to treat BIM not just as a modeling exercise, but as a programmable platform for quality, compliance, and automation across a heterogeneous toolchain.

Data governance and delivery patterns

As data volumes increased, project teams professionalized data governance. CDEs evolved beyond file sharing into API-enabled hubs supporting automated QA, packaging, and handover. Model audit scripts checked for classification coverage, property set completeness, and naming conventions before data moved downstream. Classification systems such as OmniClass, UniFormat, MasterFormat, and the UK’s Uniclass were mapped to BIM semantics to enable consistent cost coding, asset tagging, and FM integration.

Organizations increasingly adopted:

- Automated gates that validate models against project-specific information requirements before submittal.

- Packaging pipelines that generate IFC/BCF/COBie bundles tailored to recipient workflows.

- Versioned archives that align model states with decisions, RFIs, and changes for auditability.

Toward Full-Project Digital Twins: Operations, Telemetry, and Lifecycle Intelligence

What differentiates a digital twin from BIM

While BIM focuses on design intent and coordinated delivery, a digital twin is distinguished by live connections to operational systems, versioned time, and feedback loops that influence decisions during use. Twins link models to BAS/IoT through protocols like BACnet and Modbus, stream time-series telemetry from sensors and meters, and maintain asset identity and lineage from commissioning through maintenance. They support simulation-in-the-loop—reconciling predicted performance with actuals, and using control strategies or setpoint tuning informed by measured data.

Semantics are crucial. Ontologies like Brick schema and Project Haystack, and the emerging ASHRAE 223P standard, define machine-readable relationships among systems, points, and spaces. Crosswalks between Brick/Haystack and IFC preserve the durability of building handover models while adding operational meaning. The objective is to bind “where an air handling unit lives” with “which telemetry and control points represent its state,” in a way that survives vendor changes and system upgrades. This semantic layer—coupled with robust identity and time—is the practical line that separates a static BIM from a continuously evolving, decision-supportive twin.

Platforms, ecosystems, and handover patterns

The platform landscape reflects this operational emphasis. Bentley iTwin provides a graph-based backbone for federating design, reality, and time-series data; Autodesk Tandem aligns design models with operational taxonomies; Siemens Xcelerator, integrating workplace and building tech like Enlighted and Comfy, blurs the line between operations and occupant experience; Microsoft Azure Digital Twins uses DTDL to define domain models across portfolios; WillowTwin, Nemetschek dTwin, Schneider Electric EcoStruxure, and IBM Maximo integrations illustrate diverse approaches to asset-centric twins. Regardless of platform, the handover bridge remains critical: COBie delivers an owner-friendly asset register, while evolving IDS (Information Delivery Specification) profiles detail exactly which properties and relationships must be present for operations.

Facilities integration patterns increasingly include:

- Deriving an authoritative asset list from IFC and COBie, then binding assets to BAS/IoT point namespaces.

- Using IDS to validate that models carry the properties needed for CMMS, space planning, and energy reporting.

- Automated synchronization routines that align twin graphs with work orders, commissioning results, and meter hierarchies.

Challenges, frontiers, and standards trajectory

The move to twins surfaces thorny challenges. Source-of-truth governance across design–build–operate must reconcile model revisions with field changes and service events; time must be versioned for geometry, metadata, and events, not just schedules. Cybersecurity and privacy loom large as occupant analytics and location-tracking raise policy questions. A central trade-off is fidelity vs. maintainability: hyper-detailed models can decay if they are too costly to update, while lean models may lack the granularity needed for automated analytics. Automated compliance checking—across life safety, accessibility, cybersecurity, and sustainability—demands codified rules and trusted data.

Carbon analytics intensify the need for reliable data. Embodied carbon workflows align BIM quantities with product EPDs (e.g., via EC3 or One Click LCA), while operational carbon requires high-quality submeters and weather normalization. Federated model orchestration—spanning design authoring, coordination, reality capture, and telemetry—pushes standards forward. IFC4.3 adoption extends coverage to linear infrastructure; the buildingSMART IDS and Digital Twins initiatives align data delivery and operational semantics; OGC and city-model convergence tighten GIS links. Airports, hospitals, and campuses are standing examples of predictive maintenance, occupant-experience tuning, and continuous commissioning being orchestrated at scale—without naming specific projects, the pattern is unmistakable and accelerating.

Exemplars and impacts across portfolios

Sector by sector, the impacts of computable operations are becoming clearer. In aviation, complex systems and high utilization reward predictive maintenance for critical assets like chillers, baggage handling, and jet bridges. In healthcare, regulatory intensity and energy loads drive continuous commissioning and space utilization analytics linked to clinical operations. Campus portfolios use twins for lighting and HVAC optimization at scale, benchmarking buildings and feeding procurement with measured outcomes. What unites these sectors is the shift from one-off project models to portfolio-level intelligence where lessons learned move from operations back into design standards and early-phase decision tools.

Feedback loops are tightening:

- Operational anomalies trigger model updates and specification changes for the next project.

- Telemetered performance informs parametric templates, making “standard details” genuinely performance-proven.

- Portfolio analytics prioritize retrofits and replacements based on risk, cost, and carbon across the estate.

Conclusion

The throughline from object models to telemetry-enabled twins

The long arc runs from Eastman’s BDS and GLIDE, through product-model thinking shaped by STEP/EXPRESS and GARM, to commercial systems that codified constraints and object semantics. The 2000s industrialized these ideas in parametric platforms like Revit, ArchiCAD, AECOsim/OpenBuildings, and Tekla, while coordination, 4D/5D, and model checking established BIM as a delivery backbone. Open standards—IFC, COBie, and BCF—made multi-party computation possible, and process frameworks like ISO 19650 ensured information actually flowed. Mid‑2010s convergence with GIS and reality capture widened the canvas to city scale, while computational design and open tooling made BIM programmable.

Now, digital twins add time, telemetry, and operational semantics. Ontologies like Brick, Haystack, and ASHRAE 223P connect models to live systems, while platforms from iTwin to Azure Digital Twins operationalize governance and analytics. The center of gravity is shifting toward durable semantics, trustworthy data management, and automation that spans from early design to long-term operations. As the industry aligns on federated, standards-based twins, lifecycle carbon will drop, performance will improve, and portfolios will optimize continuously—fulfilling the early vision of computable buildings at urban scale.

What comes next

Expect deeper convergence among IFC4.3, IDS, and city/GIS standards, with CDEs acting as integration fabric for model states, issues, and event streams. Automated compliance will become routine as rulesets mature and authorities accept machine-checkable submissions. Carbon accountability will integrate upstream supply-chain data and downstream telemetry, closing the circle from embodied to operational performance. Most importantly, owners and delivery teams will treat models as living assets: versioned across time, validated against reality, and enriched by feedback from occupants and operators.

The guiding principle remains simple: make data explicit, portable, and provable. With that foundation, the next wave of gains will come not from a single breakthrough tool, but from a harmonized ecosystem—open schemas, robust governance, and programmable workflows—that turns information into measurable outcomes. In this sense, BIM’s evolution into digital twins is not a departure but a culmination: a decades-long progression toward computable, interoperable, and continuously improving buildings and infrastructure.

Also in Design News

Fast Concept-Stage Simulation: Multi-Fidelity Feedback, Credibility, and UX for Shift-Left Design

December 03, 2025 12 min read

Read More

Rhino 3D Tip: Measure and Mass Properties for Early Design Validation

December 02, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …