Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History: Constraint Solving in CAD: From Sketchpad to Modern Parametric Engines

December 31, 2025 12 min read

From Early Notions to Industrial Sketchers: Milestones, People, and Companies

Sketchpad and the seed of constraint-based thinking

The roots of modern parametric sketching trace back to the early 1960s and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, a system that introduced interactive graphics, hierarchical instances, and geometric relations that presaged today’s constraint solvers. Sketchpad’s “rubber band” vectors and explicit relationships between entities demonstrated that a drawing could be more than static lines; it could respond to the user by maintaining constraints. Although Sutherland did not ship a commercial variational solver, the conceptual groundwork was unmistakable: the notion that geometric elements should honor conditions like perpendicularity and coincidence while the system dynamically adjusts coordinates is the template for later CAD behavior. The direct manipulation of nodes, the “light pen,” and the visual feedback loop foreshadowed the practical loop of editing and recomputation that defines constraint-based sketching. In the decade that followed, related ideas surfaced in works by Steven Coons and in early interactive graphics projects, but it would take a generation for those principles to coalesce into commercial-grade engines. The key shift was mental: from a static geometric picture to a graph of relationships that define a family of valid shapes. That conceptual pivot is the throughline from Sketchpad to the modern CAD sketch—an early understanding that the designer’s intent could be formalized as constraints and preserved through edits, the essence of constraint-based sketches.

Parametrics becomes product-defining: Pro/ENGINEER, SolidWorks, and Inventor

By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, parametrics moved from research curiosity to market advantage. PTC’s Pro/ENGINEER (founded by Dr. Samuel Geisberg, with key early leaders including Steve Walske and Mike Payne) popularized feature-based modeling where sketches, variation, and ordered feature history were tightly coupled. In Pro/ENGINEER, each sketch carried dimensions and geometric constraints; those parameters drove extrudes, revolves, and cuts, all logged in an ordered model tree that recomputed predictably on change. The architectural decision—link a variational sketch to a feature in a deterministic regeneration order—made parametrics a product-defining capability. SolidWorks, founded by Jon Hirschtick with Mike Payne later joining, brought that paradigm to mainstream Windows workstations in 1995, blending an approachable UI with robust sketch inference and constraints. Autodesk followed with Inventor (leveraging the ShapeManager kernel derived from ACIS), focusing on aggressive constraint inference, glyphs for degrees of freedom, and widespread automatic dimensioning to help new users encode design intent. The result was an industry-wide shift: geometry ceased being a passive description and became an active system of equations with a user interface. As teams standardized on feature-driven workflows, the sketch solver evolved into a strategic core: stability, diagnostics, and predictability became differentiators. This era set expectations that constraints would be fast, understandable, and resilient under change, laying the foundation for the solver engines and UX conventions we still recognize today.

Commercial solver engines emerge: D‑Cubed and LEDAS

As parametrics matured, independent constraint solver components emerged, enabling vendors to license specialized technology rather than building it from scratch. Engineering Geometry Systems (EGS), led by John Owen in the early 1990s, introduced the 2D DCM (Dimensional Constraint Manager), a compact engine designed to solve geometric and dimensional constraints in sketches. EGS was acquired by UGS, and the technology was rebranded as D‑Cubed when UGS consolidated its component strategy; later, Siemens acquired UGS, and D‑Cubed continued to evolve under Siemens Digital Industries Software. Beyond 2D DCM, D‑Cubed expanded into 3D DCM for spatial constraints, the Assembly Constraints Manager (ACM) for mating parts with kinematic degrees of freedom, and the Collision Detection Manager (CDM) for robust interference and contact analysis. Parallel to this, LEDAS, founded by Alexander Tzukanov with key technologists including Dmitry Ushakov and Alexey Andreev, built the LGS 2D/3D solvers, emphasizing flexible constraint formulations and extensibility. LEDAS’s solver technology later powered advanced parametrics within Bricsys’s BricsCAD, where it undergirded 2D sketch constraints and 3D direct-modeling relations on faces and edges. These component ecosystems established a de facto standard: a CAD vendor could focus on UI, workflows, and kernel integration while relying on a specialized team to push the frontier of stability, speed, and diagnostics in constraint solving. The industrialization of these engines made parametrics both ubiquitous and consistent across tools.

Open and academic influences: SolveSpace, FreeCAD, and foundational theory

While commercial engines proliferated, open and academic efforts amplified innovation and accessibility. Jonathan Westhues’s SolveSpace demonstrated a compact open-source variational solver and modeling environment, showcasing how a carefully implemented Newton-based engine with attention to Jacobians and rank deficiency could provide crisp constraint behavior and clean diagnostics. FreeCAD, led by an active global community and contributions from developers like Abdullah Tahiri, grew a custom Levenberg–Marquardt-style solver in its Sketcher workbench, balancing performance with robust constraint sets and a rich UI for degrees of freedom visualization. Underpinning these systems is a body of research: Christoph M. Hoffmann and Pere Joan–Arinyo developed graph-based decomposition methods and DR-plans to partition constraint systems into solvable subsets; Ioannis Fudos advanced constructive approaches that produce consistent build sequences; Meera Sitharam contributed rigor via rigidity theory and geometric constraint solving using dependency and decomposition strategies. The broader constraint satisfaction community introduced ideas like constraint hierarchies and the Cassowary solver (Alan Borning, Greg Badros, and Peter Stuckey) that, while born in UI layout, cross-pollinated priorities and soft constraints into CAD thinking. Together, these open and academic threads ensured that constraint solving remained transparent, explainable, and continuously evolving, while also seeding educational tools that nurture the next generation of CAD solver engineers.

Inside the Engines: Models, Methods, and Data Structures

Problem formulation: variables, constraints, and the variational core

At the heart of every sketch solver lies a variational problem: find parameter values x such that F(x) = 0, where F encodes geometric and dimensional constraints. The vector x includes unknowns like point coordinates, angles, distances, radii, and sometimes auxiliary parameters such as orientation quaternions or scaling factors. The solver builds a Jacobian J = ∂F/∂x and iteratively updates x using Newton or Levenberg–Marquardt steps. Stabilization comes from damping, trust regions, and careful scaling of equations. Detecting rank deficiency in J is crucial; it reveals redundant or conflicting constraints and provides an accurate count of free motion, i.e., degrees of freedom (DOF). Practical solvers layer additional bookkeeping to distinguish between global gauge freedoms (e.g., rigid motions in 2D) and design-relevant DOF. Typical constraint sets include:

- Geometric: coincidence, collinearity, parallel, perpendicular, equal length, symmetry, concentricity, tangency, horizontality/verticality.

- Dimensional: distances, angles, radii/diameters, offsets, and equations linking parameters.

- Topological references: entity identities, constraints referencing edges, curves, and construction geometry.

Graphs, decomposition, and constructive sequences

Variational methods succeed or fail on initialization and structure. Constraint graphs organize entities as nodes and constraints as edges, enabling decomposition into tractable subproblems. Building on ideas from Hoffmann and Joan–Arinyo, DR-plans (decomposition-recombination plans) recursively identify clusters that can be solved independently and then stitched together. Early detection of under- and over-constraint leverages Laman-like counting from rigidity theory, flagging systems with too few or too many constraints before costly numerics attempt a doomed solve. Constructive approaches (as advanced by Ioannis Fudos and others) order the build using triangulation or Henneberg steps, yielding seed configurations that feed the numeric solver with viable initial estimates. The benefits of these graph-driven strategies are concrete:

- Reduced problem size via clustering and separation of weakly coupled regions.

- Improved robustness from good initial guesses that avoid singularities and flipped configurations.

- Faster incremental updates by localizing edits and preserving results in unaffected clusters.

Algebraic and hybrid strategies: exactness meets numerics

Purely numerical solvers can struggle with singular cases, bifurcations, or near-degenerate configurations. To combat this, engines incorporate algebraic techniques in small, targeted doses. Symbolic elimination using resultants or Gröbner bases can resolve tight sub-systems exactly (e.g., circle-line tangency pairs), producing closed-form relations or reducing variable counts. Numeric continuation and homotopy methods trace solution paths from an easy instance to the target problem, which is valuable when multiple configurations exist or when the system transitions across regimes. Interval and exact rational arithmetic appear in research prototypes for robustness, but production systems usually constrain their use to narrow hotspots due to performance. The pragmatic pattern is a hybrid pipeline:

- Partition the system; tackle tiny algebraic kernels exactly to simplify the global numerics.

- Use homotopy for ambiguous configurations where initial guesses matter.

- Fallback to damped Levenberg–Marquardt with adaptive scaling when the landscape is ill-conditioned.

UX layers and robustness: inference, priorities, and conditioning

The visible layer of constraint solving is not the Jacobian; it is the user experience that makes intent capture fluid and errors understandable. Inference engines watch mouse gestures and geometry to propose constraints as you draw, while auto-dimensioning seeds sketches with sensible parameters to reduce ambiguity. DOF glyphs and live manipulators communicate what can move. When conflicts arise, solvers diagnose redundancy and inconsistency and suggest removals or priorities. Constraint hierarchies and soft weights—concepts inspired by Cassowary and constraint-based UI layout—help CAD handle competing aims (e.g., maintain parallelism, but prefer this dimension to change). Inequality constraints capture fit conditions, limits, and offsets that must not be violated. To keep iteration stable, engines normalize units, scale equations to comparable magnitudes, and reparameterize (e.g., angles instead of slopes, log-parameters for strictly positive lengths). Effective UX patterns include:

- Previewing which constraints will be created before mouse release.

- Local solves during drags, with continuous feedback and stable motion.

- Contextual conflict explanations mapping algebraic causes to editable items.

From Sketches to 3D, Assemblies, and Direct Modeling

3D mates, kinematics, and contact: from 2D DCM to ACM and CDM

Extending constraint solving into 3D generalizes 2D relations and introduces orientation, frames, and rigid-body kinematics. The 3D DCM enforces relations such as coincident faces, concentric cylinders, parallel or perpendicular planes, and distance/angle constraints between reference frames. Assembly-level solvers like the Assembly Constraints Manager (ACM) treat parts as rigid bodies with six DOF, attenuated by mates that reduce translational and rotational freedom. Managing DOF becomes both a mathematical and a design problem: the solver must ensure that mates are neither conflicting nor leaving uncontrolled drift in critical directions. In dynamic contexts, collision detection from the Collision Detection Manager (CDM) integrates with motion, adding contact constraints and clearances. Typical 3D assembly stacks track:

- Rigid transforms for each component relative to an assembly reference.

- Mate equations expressed in frame parameters (e.g., axis alignment and offset).

- Kinematic loops where the solver identifies dependent constraints and floating sub-assemblies.

The ecosystem and who used what

Constraint engines became shared infrastructure across the CAD landscape, with D‑Cubed licensing shaping a broad ecosystem and other engines enabling differentiation. The following patterns have been especially influential:

- Widespread D‑Cubed adoption: SolidWorks, Autodesk Inventor and Fusion 360 (via ShapeManager), Siemens NX and Solid Edge, and Onshape (combining Parasolid with D‑Cubed) embedded D‑Cubed components like 2D/3D DCM, ACM, and CDM.

- PTC’s in-house stack: From Pro/ENGINEER to Creo, PTC maintained a proprietary parametric engine tightly integrated with its regeneration order and feature system, prioritizing deterministic change propagation.

- LEDAS technology in BricsCAD: Bricsys incorporated LEDAS LGS solvers and the derivative ecosystem from LEDAS’s “Driving Dimensions,” which influenced downstream tools for constraint-driven 3D edits on faces and solids.

- AEC/BIM cross-pollination: Autodesk Revit introduced a building-focused parametric change engine where dimension-driven constraints govern walls, windows, and levels, translating mechanical sketch ideas into architectural semantics.

Direct and synchronous modeling meets constraints

As direct modeling grew in popularity, vendors reconciled push-pull edits with persistent design intent. Siemens’ Synchronous Technology introduced on-the-fly inference and maintenance of geometric relations on faces—parallelism, coplanarity, concentricity—so a direct move preserved a constraint-consistent state. PTC Creo Flexible Modeling and Autodesk Fusion integrated similar ideas, blending feature history with constraint-aware direct edits and optional capture of detected relations. The pipeline typically involves:

- Feature and topology recognition to identify patterns (e.g., holes, blends, symmetric groups) on imported or native geometry.

- Relation inference that builds a constraint set among faces and edges (parallel, equal radius, symmetry) to preserve coherence during direct moves.

- A variational step that adjusts neighboring geometry to satisfy the inferred constraints while honoring user manipulations.

Scaling to real products: performance, topology change, and arithmetic

Industrial models push solvers beyond tidy demos: they involve large, uneven sketches, mixed units, imported geometry with imperfect topology, and edits that cascade across assemblies. To cope, engines deploy incremental update strategies that detect affected regions, cache linearizations, and prefer local re-solves over full recomputation. Large sketches benefit from partitioning into zones and from caching factorized Jacobians for repeated edits. Topology change—when edges split or disappear after a fillet or a boolean—demands persistent identifiers and constraint remapping rules so that relations survive kernel operations. Solver-tolerant kernels help by preserving edge/face identity through common operations and by providing stable geometric queries under small perturbations. Vendors balance robustness with speed using:

- Persistent IDs and name-mapping heuristics aligned with kernel topology evolution.

- Constraint remapping and validation when references shift or collapse.

- Selective use of exact/rational arithmetic for critical predicates, with floating-point numerics elsewhere for performance.

Conclusion

From interactive relations to graph-driven design intelligence

Constraint solving transformed sketches from static drawings into living models that encode and preserve design intent. The arc runs from Sketchpad’s interactive relations, through Pro/ENGINEER’s feature-driven parametrics and SolidWorks’ mainstream adoption, to a mature ecosystem of engines where D‑Cubed (originating with John Owen at EGS, later under UGS and Siemens) and LEDAS (with Dmitry Ushakov and Alexey Andreev) power both 2D and 3D. Academic foundations from Christoph M. Hoffmann and Pere Joan–Arinyo’s decomposition methods, Ioannis Fudos’s constructive approaches, and Meera Sitharam’s rigidity-theoretic frameworks, plus ideas from the constraint satisfaction community like Cassowary’s hierarchies, crystallized into practical, explainable solvers. Open systems such as SolveSpace and FreeCAD ensured transparency and education, while production tools integrated constraints across sketches, solids, assemblies, and direct modeling. Today’s best practice is a hybrid: graph decomposition and constructive seeding coupled with Newton/Levenberg–Marquardt numerics, layered with inference, prioritization, and robust diagnostics. As engines expanded to assemblies, collision and contact constraints turned mates into kinematic systems, uniting geometry, motion, and intent. The result is a discipline where variational solvers underpin product development from ideation to manufacturing, enabling edits that are both flexible and principled.

Enduring challenges and likely next steps

As models and teams scale, so do the demands on constraint engines. The road ahead is shaped by several enduring challenges and opportunities:

- Robustness at scale: defeating ill-conditioning from disparate dimensions, surviving topology change with stable remapping, and diagnosing conflicts in sprawling, multi-author models.

- Expressiveness: richer inequalities, contact/compliance models, and prioritized hierarchies that better reflect real-world constraints and tolerances in both mechanical and AEC domains.

- Performance: smarter decomposition, incremental re-solve, and parallel linear algebra tuned for cloud-native, collaborative CAD where latency must stay sub-perceptual.

- Interoperability: harmonizing constraint semantics across kernels and vendors so that intent round-trips cleanly through neutral formats and supply chains.

Also in Design News

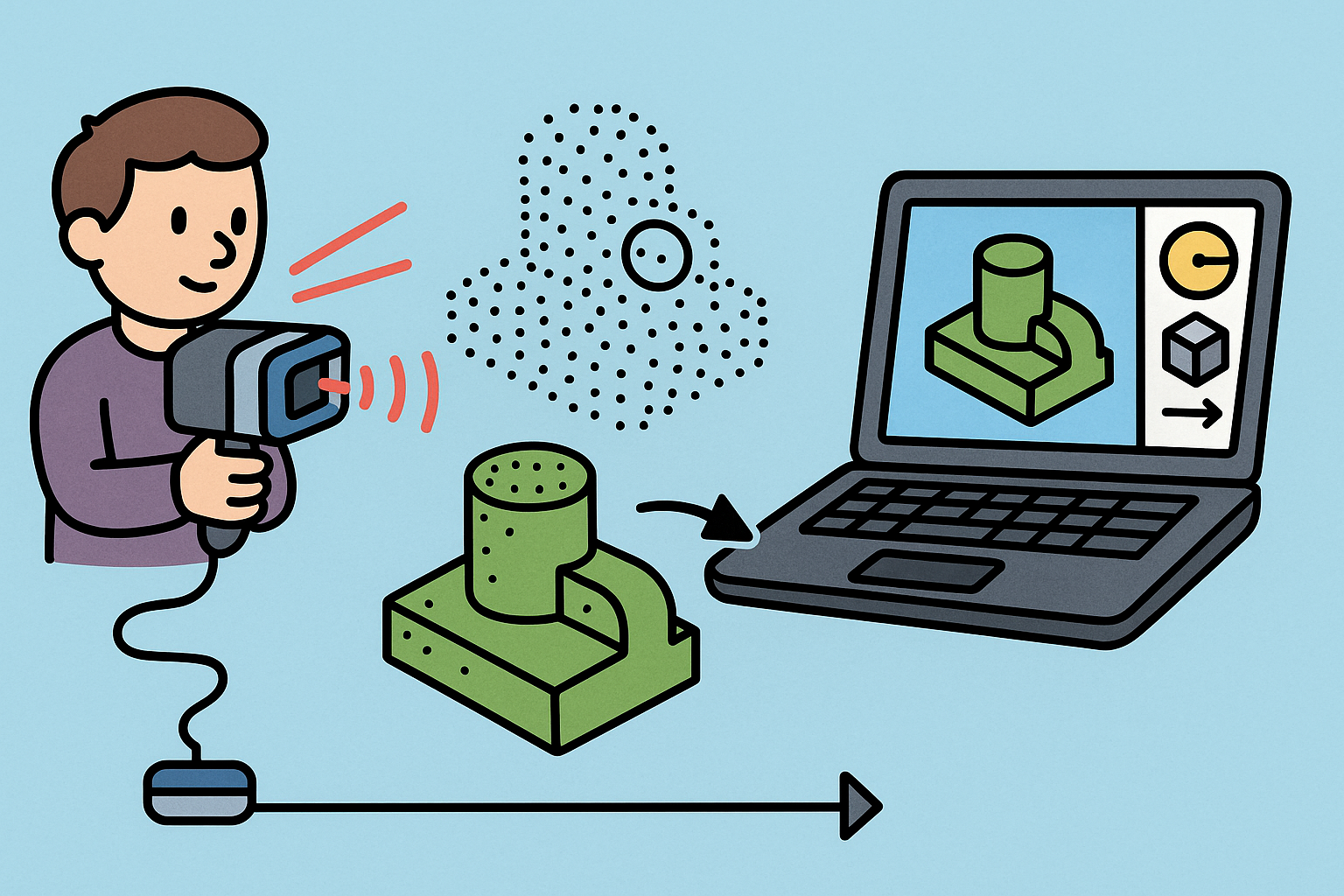

Intent-Aware Scan-to-BRep: Integrating LiDAR Point Clouds into Solid Modeling Pipelines

December 31, 2025 12 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Hand-Painted Vertex Maps — Fast Workflow for Deformers, MoGraph, and Material Masks

December 31, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …