Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

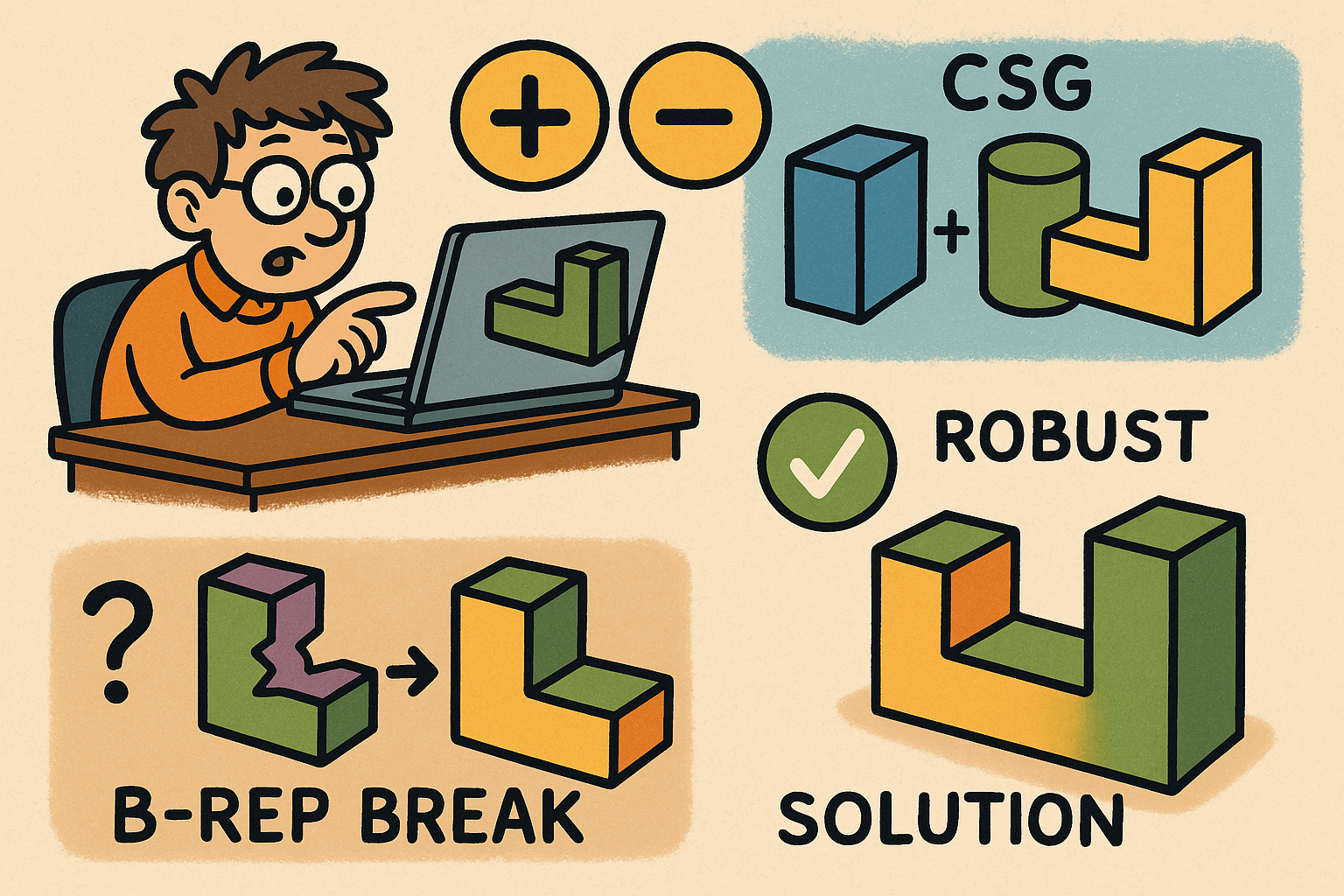

Design Software History: Boolean Modeling in CAD: CSG Origins, B‑Rep Breaking Points, and Robustness Solutions

December 07, 2025 15 min read

A short history of Boolean modeling and its breaking points

From CSG logic to manufacturable solids

The story of Boolean modeling in design software begins with the clarity of Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG): a small set of volumetric primitives (blocks, cylinders, cones, spheres, tori) combined by union, difference, and intersection to build complex parts. In the 1970s and early 1980s, researchers such as A.A.G. Requicha and H.B. Voelcker at USC/PADL formalized the mathematics of regularized sets and developed algorithms for evaluating CSG trees. Their insistence on regularization—removing lower-dimensional flotsam (dangling edges, isolated points) and guaranteeing closed interiors—gave industry a coherent definition of what a solid is. That foundation influenced how systems classify space during Booleans, determine interior/exterior, and avoid paradoxes. In parallel, Jarek Rossignac’s work on r-sets made the connection between algebraic set formulations and the engineering expectations of watertight, manufacturable geometry even tighter. The early CSG era thus established a compact, testable semantics: if the model is a regular set, then its boundary is well-defined and fabrication processes—toolpaths, casting, and later additive manufacturing—can trust it.

But practical use demanded more than pristine theory. Designers quickly needed free-form blends, drafts, and sculpted surfaces beyond primitive trees. As the scope widened, the question shifted from “How do we evaluate a CSG tree?” to “How do we represent and edit the resulting shape’s boundary?” This pressure set the stage for the transition to B‑rep (boundary representation), where the topology of faces, edges, and vertices is explicit, allowing fillets, shells, variable-radius blends, and advanced surface modeling. The ensuing decades would be defined by reconciling CSG’s clarity with B‑rep’s flexibility—while keeping Booleans reliable enough not to wreck downstream manufacturing and simulation.

Boundary representations and the rise of kernels

The move to Boundary Representation (B‑rep) became inevitable as designers demanded freeform surfaces and complex topologies. In Cambridge, Shape Data’s team—Ian Braid, Alan Grayer, and Charles Lang—built Romulus, one of the first robust B‑rep kernels, and later laid the groundwork for Parasolid, which evolved under Siemens’ stewardship into the dominant kernel powering NX, SolidWorks, and Onshape. In the United States, Dick Sowar founded Spatial Technology to commercialize ACIS, whose hybrid analytic/NURBS capabilities attracted application vendors; Autodesk forked ACIS to create ShapeManager, an internal kernel that underpins Inventor and Fusion 360. On the European side, Matra Datavision launched Open CASCADE, today known as OCCT (Open CASCADE Technology), which remains the most widely used open-source B‑rep and surface modeling kernel in heavy industry and research. Dassault Systèmes developed the CGM kernel for CATIA and 3DEXPERIENCE apps, while PTC’s Granite powered Pro/ENGINEER and Creo. This kernel ecosystem professionalized and monetized the art of Booleans—turning them into a service delivered through APIs used by countless CAD applications.

Each kernel evolved a portfolio of intersection routines, topology creation strategies, and tolerance policies, because Boolean operations—no matter how simple they appear in the UI—are an orchestration of face–face intersection, curve trimming, vertex creation, and topological sewing. Parasolid invested heavily in reliable face–face intersection and sliver suppression; ACIS/ShapeManager emphasized imprint/sew/heal workflows to stabilize subsequent features; OCCT added “fuzzy” parameters and the General Fuse pipeline to cope with near-coincident inputs. Dassault’s CGM specialized in high-order surface continuity and large-assembly robustness demanded by aerospace clients. Although SolidWorks is famously based on Parasolid rather than CGM, Dassault’s internal knowledge from CGM influenced data exchange and robustness practices across the company’s portfolio. The commercial maturation of Booleans thus became a study in engineering tradeoffs: speed versus exactness, tolerance breadth versus predictability, and editable history versus algorithmic simplicity.

CSG’s robust outlier: BRL‑CAD and ray classification

While the commercial sector gravitated toward B‑rep, BRL‑CAD, initiated by Mike Muuss at the U.S. Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory, preserved the CSG ideal in large-scale, production-grade environments. Its secret weapon was not a B‑rep at all, but ray‑traced classification: spatial queries determine whether points lie inside or outside the CSG solid by tracing rays and counting boundary crossings with careful regularization. This approach scales surprisingly well to complex assemblies and ambiguous configurations because it sidesteps many topological ambiguities that plague B‑rep Booleans. The ray-evaluation model also aligns naturally with rendering and ballistic simulation, letting a single representation serve design, visualization, and analysis without converting to B‑rep.

BRL‑CAD did not prevent the industry’s pivot to B‑rep modeling, but it provided a persistent proof that robust classification can be achieved using a different paradigm. By avoiding explicit stitching of faces and edges during Boolean evaluation, it limits the creation of non-manifold junk at its source. The system’s longevity—decades of continuous use—also highlights another lesson the commercial kernel world later embraced: reliability emerges from regression discipline, carefully chosen predicates, and algorithmic humility about floating‑point arithmetic. In a world where sleek surfacing tools took the spotlight, BRL‑CAD quietly maintained a robustness bar that many B‑rep pipelines struggled to meet.

Where practice broke: catastrophic failure modes

As B‑rep Booleans became the norm, users ran into painful, repeatable failure modes. The worst offenders were the visual and topological catastrophes that left models unusable. Practitioners encountered:

- Non‑manifold edges/vertices: topological junctures with ambiguous interior/exterior classification, breaking downstream meshing and CAM.

- Sliver and needle faces: faces with extreme aspect ratios generated by grazing intersections or numerically noisy trims.

- Self‑intersections and missing faces: trimming operations that created overlapped patches or left holes in shells.

- Open shells after union/diff/intersect: nominally closed solids that leaked due to tolerance mismatches or wrong-side trims.

Each of these defects destroyed trust. A designer could lose hours to a failed union between nearly coplanar parts; a CAM programmer could receive an STL riddled with gaps after a difference operation; a CAE analyst could find that a mesh generator refuses to proceed because the part is non‑manifold near a tiny fillet. This class of failures birthed a cottage industry of “geometry healing” tools and workflows across the 1990s and 2000s, from Parasolid’s sew/repair to ACIS’s imprint/heal and OCCT’s Shape Healing. The lesson was sobering: elegant mathematical models do not guarantee robust computation when geometry spans wide scales, tolerances vary, and floating‑point arithmetic sits underneath every comparison.

Degeneracy, scale, and the industry’s tolerance wars

Not all failures explode spectacularly; some lurk as near-degenerate arrangements that poison classification. Tangential contacts masquerade as intersections; near-coplanar faces lead to unstable trim curves; coincident edges generate duplicate topology that confuses later features. These phenomena are magnified in real models that mix units and scales—think micrometer fillets on meter-scale assemblies—and by system tolerances that must bridge the two. A Boolean that “succeeds” numerically, but introduces faces whose size falls below modeling epsilon, is often worse than a clean failure, because the defect will surface downstream during shelling, filleting, or meshing.

The 1990s–2000s are littered with user reports about unstable Booleans in popular MCAD systems and surface modelers. Organizations learned to institute geometry hygiene before CAE or CAM: verifying watertightness, removing slivers, and snapping near-coincident boundaries. Tool vendors responded with tolerant modeling philosophies—accept tiny inconsistencies within a controllable envelope, document the implications, and provide repair tools. Yet even tolerant regimes faced contradictions: make tolerances too tight and models fail to stitch; make them too loose and topology loses meaning. The era thus framed the central challenge: marrying numerical pragmatism with topological integrity so that Boolean operations are both permissive enough for real-world data and strict enough for downstream determinism.

Why Booleans are hard: the numerical and topological roots

Floating‑point arithmetic and the fragility of intersection

At the heart of every Boolean lies an intersection problem: compute where curves meet curves, curves meet surfaces, and surfaces meet surfaces—often among a zoo of NURBS patches and analytic primitives. In floating‑point arithmetic, this is a minefield. Subtractive cancellation erases significant digits when evaluating nearly tangential intersections, and ill‑conditioned root‑finding magnifies tiny input errors into large output discrepancies. When two bicubic NURBS surfaces intersect with shallow angle, the curve of intersection can be exquisitely sensitive to control point noise and parameterization choices; the multiplier effect can turn a robust pipeline brittle. Add to that mixed model scales—small features on large spans—and one quickly appreciates why a naïve “solve and trim” approach fails.

Many kernels adopted strategies to mitigate these realities. Common techniques include using filtered predicates that make fast decisions when the answer is far from ambiguous, then escalate to higher precision near decision boundaries; applying interval arithmetic to bound root locations safely; and employing safeguarded Newton iterations with bracketing to avoid divergence. Yet, even with care, it is classification that makes or breaks the result: determining whether a point or edge is inside, outside, or on a boundary relies on distance comparisons against tolerances. When that epsilon is too large relative to local curvature or feature size, features vanish; when it is too small, trivial noise triggers topological splits. The numerical truth is harsh: robust Booleans are not a single algorithm but a set of defensive layers that negotiate with floating‑point limitations.

Topology, invariants, and geometry–topology consistency

B‑rep modeling is as much about topology as it is about geometry. The Euler–Poincaré relationship provides invariants that must hold for closed orientable solids, dictating how faces, edges, and vertices can relate. Enforcing these invariants during a Boolean is nontrivial because the topology is not simply derived after the fact; it is created in tandem with intersection geometry and trimming. Non‑manifold configurations tempt algorithms when coincident or near-coincident features arise, and without explicit checks, it is easy to create a vertex where the incident edges do not support a consistent orientation. The geometry–topology consistency problem—ensuring that parametric trims, 3D curves, and underlying surfaces agree within tolerance—is the daily battle of kernel engineers.

Industrial pipelines therefore encode many safeguards: snapping newly created vertices to existing ones if they lie within a tolerance (to avoid proliferating duplicates); reparameterizing trims so that curve–surface distance stays bounded; and running manifoldness checks to ensure each topological edge has exactly two face uses with opposite orientations in a closed solid. Even so, the strict imposition of topological rules must be balanced against user expectations. Users want coincident faces to remain coincident when appropriate; they want sewing to succeed without extensive manual intervention; they expect shelling and filleting after a Boolean to respect continuity constraints. Each of these expectations feeds back into the core Boolean algorithms, dictating whether and how to merge near-coincident entities and how to represent ambiguous areas without breaking invariants.

Regularization, exact predicates, and adaptive precision

The concept of regularized set operations—pioneered in CSG literature—remains a cornerstone for robustness. By definition, a regularized union, difference, or intersection removes dangling lower-dimensional artifacts and ensures that results are closed sets. In practice, that means trimming or discarding fragments that fail to reach dimensional significance under the kernel’s tolerance regime. But regularization alone cannot save computations performed with floating‑point arithmetic when decisions hinge on ambiguous comparisons. This is where the Exact Geometric Computation (EGC) paradigm, championed by Chee Yap, and exact/filtered predicates, popularized by Jonathan Shewchuk, stepped in. The idea is simple yet powerful: use fast floating‑point evaluations when safe, but automatically escalate to robust exact arithmetic when the sign of a predicate (orientation, incircle, sidedness) is uncertain.

These techniques can be combined with smart algorithmic structures. For instance, robust orientation tests feed edge–edge intersection routines, which then guarantee that the resulting arrangement of segments is combinatorially consistent. With exact predicates, downstream meshing and classification are less likely to disagree about sidedness. However, kernels that prize interactive performance rarely run everything in rationals; instead, they adopt a layered approach: filtered predicates at the front, interval arithmetic to track uncertainty, and rational or arbitrary-precision arithmetic as a last resort for truly degenerate scenarios. This adaptive precision model, when paired with regularized outcomes, dramatically reduces catastrophic failures without forcing users to accept unacceptable slowdowns.

Symbolic handling of degeneracies and arrangements

Degeneracies—coincident points, collinear edges, tangential intersections—are not corner cases in industry; they are the norm. Symbolic frameworks were created to tame them. Edelsbrunner and Mücke’s Simulation of Simplicity perturbs configurations in a controlled, symbolic manner so that algorithms can proceed as if in general position and then map results back consistently. Snap rounding, introduced by Leonidas Guibas and collaborators, rounds intersection points to a grid while preserving topological embedding, thus avoiding the combinatorial explosion of nearly coincident vertices. On the polyhedral side, arrangements and Nef polyhedra (after W. Nef) provide exact Boolean operations that can represent open, closed, and even non-manifold structures under precise arithmetic.

These ideas coalesced in libraries such as CGAL, where work by Dan Halperin, Efi Fogel, and Oren Wein on arrangements underpins robust polyhedral Booleans. The Nef_3 package, for example, executes Booleans exactly on polyhedra by maintaining consistent arrangements on spheres and planes with exact predicates and constructions. While computationally heavier than B‑rep/NURBS pipelines, such methods offer a correctness backstop: when exactness matters—such as for verification, certification, or tricky degeneracies—they avoid the numerical quicksand that traps floating‑point-only approaches. Industrial kernels increasingly blend these symbolic techniques into their numeric routines, using them selectively where ambiguity threatens the integrity of the result.

Classification, tolerances, and the peril of epsilon

After intersections are computed, Booleans reduce to classification: for each candidate face, edge, or vertex, decide whether it belongs to the result, and, if so, with what orientation. This sounds simple but hides the hardest judgments because the decision thresholds live near floating‑point limits. Distance-to-surface comparisons, point-in-solid queries, and side-of-curve tests all lean on tolerances. Inconsistent tolerances—across parts, features, or imported data—create contradictory truths: an edge that is “on” a surface for one operation is “off” for another. Careful kernels establish a hierarchy of tolerances and enforce monotonicity: once an entity is deemed within tolerance, subsequent operations remember it. Some workflows even retain certificates—metadata proving why a classification decision was made—so that later features can respect it.

Ultimately, numerics and topology are inseparable. The Boolean operation is where they collide: intersections must be solved within accuracy bounds large enough to be practical and small enough to preserve topology; resultant topology must be pruned and regularized without erasing legitimate features; and classification must be consistent so that subsequent edits do not undermine earlier truths. The sophistication of modern kernels is less about any single algorithm and more about the choreography of these interdependent pieces.

The solution toolbox: algorithms, kernels, and industrial practice

Algorithmic strategies that actually work

Decades of experience have distilled a handful of strategies that make Booleans predictable at scale. First, feed the entire pipeline with robust predicates guarded by floating‑point filters. Use fast arithmetic when the answer is unambiguous; only escalate to exact or interval arithmetic when uncertainty looms. Second, embrace tolerant modeling as an explicit design choice: model sewing, healing, imprinting, and topology repair are not afterthoughts but front‑line defenses that convert messy real-world inputs into consistent B‑reps. Third, where appropriate, employ exact polyhedral pipelines such as CGAL’s Nef_3 when correctness must trump speed or when NURBS complexity makes ambiguity unavoidable. Finally, recognize the potency of hybrid approaches: run with exact predicates and approximate constructions for 95% of cases; detect pathological instances and hand them to a precise arrangement-based backstop.

Practical implementations tend to follow a pattern:

- Intersect with filters; bound uncertainty with intervals; fall back to rationals as needed.

- Imprint all intersections on both operands to ensure symmetric trimming and consistent topology.

- Sew and heal aggressively within documented tolerances; merge near-coincident entities deterministically.

- Regularize results to remove sub‑tolerance shards; ensure manifoldness where the modeling paradigm demands it.

- Capture classifications and certificates so later features cannot silently reverse decisions.

This approach does not eliminate all failures, but it makes them rare, explainable, and fixable within engineering workflows. The key is acknowledging that Boolean robustness is not one algorithmic breakthrough; it is an ecosystem of checks, balances, and fallbacks.

Parasolid’s long campaign against slivers and ambiguity

Parasolid, originating from Shape Data’s lineage and now under Siemens, has invested for decades in face–face intersection reliability and sliver mitigation. Powering NX, SolidWorks, and Onshape simultaneously has created a crucible of diverse use cases: automotive surfaces, consumer-product blends, and parameterized mechanical parts all stress the same core Boolean routines. Over time, Parasolid refined strategies such as robust projection of intersection curves onto parametric surfaces, symmetric imprinting to avoid one-sided trims, and sliver elision through area/angle thresholds that cooperate with tolerances. Its tolerant modeling ethos avoids overzealous exactness, preferring predictable behavior under controlled epsilon. The result is not perfection but consistency; workflows built on Parasolid can bank on Booleans that either succeed cleanly or fail with diagnostics that point to repairable geometry rather than silent corruption.

Crucially, this reliability is amplified by scale: Siemens and its partners maintain massive regression suites spanning thousands of customer models. Telemetry from cloud-delivered tools—Onshape in particular—feeds continuous improvement by surfacing corner cases seen across global user bases. This testing culture is as important as any numeric trick. It embodies a recognition that robustness depends on the distribution of real inputs, not just synthetic benchmarks. The kernel’s maturity has come to define user expectations of Booleans in mainstream MCAD, shaping how designers structure features and how downstream tools trust the geometry.

ACIS/ShapeManager and the discipline of sew/heal workflows

Spatial’s ACIS pioneered accessible API layers for imprint, sew, and heal, which later informed ShapeManager at Autodesk after the ACIS fork. Autodesk Inventor and Fusion 360 have normalized workflows where users, importers, and automated tools apply sewing to form watertight solids from surface data, heal small gaps, and imprint intersections before Booleans. This pipeline acknowledges that real-world models—especially those imported from heterogeneous systems—arrive with imperfect continuity, mixed tolerances, and slight misalignments. By leaning into pre-Boolean conditioning, ShapeManager stabilizes downstream operations, making Boolean operations less surprising and easier to diagnose when they do fail.

In practice, these systems couple intersection algorithms with topology repair: a difference operation that would otherwise produce dangling micro-faces first triggers imprinting that aligns trims on both operands, then sewing that merges adjacent faces where permissible, and finally healing that adjusts boundaries within declared tolerances. The effect is cumulative. Each step narrows the room for numerical ambiguity and topological mismatch, bringing the model into a safe corridor where the Boolean can complete consistently. For designers, the discipline may feel invisible—just another operation in the history tree—but it is a large part of why modern mid-market CAD holds up under daily use.

CGM and OCCT: continuity, scale, and fuzzy Booleans

CGM, Dassault Systèmes’ kernel for CATIA and the 3DEXPERIENCE platform, evolved within automotive and aerospace ecosystems that demand high-order surface continuity, large assemblies, and strict classification at scale. Its Boolean stack emphasizes continuity-preserving trims, robust handling of skins/surfaces before solidification, and classification that copes with industrial tolerances spanning kilometers down to microns. Meanwhile, Open CASCADE Technology (OCCT) has matured through an open community that pushed robustness from many angles. OCCT’s BOPAlgo module and its General Fuse pipeline introduced fuzzy parameters that explicitly accept near-coincident and near-coplanar inputs, letting the kernel treat almost-touching surfaces as intentional intersections according to user-supplied thresholds. This “fuzziness” is not a surrender to sloppiness; it is a documented contract for predictable outcomes on ambiguous inputs.

OCCT’s openness has sparked contributions from aerospace, shipbuilding, and research organizations, each contributing fixes to degeneracy handling, stitching, and classification. Over time, the kernel’s Boolean performance and predictability improved enough to power serious commercial applications and data exchange utilities. The takeaway is that both highly curated commercial environments (CGM) and community-driven projects (OCCT) converge on similar themes: accept that inputs are imperfect; provide explicit knobs for tolerances and fuzz; and pair strong intersection code with systematic topological repair and invariants checking. Where Parasolid and ShapeManager emphasize controlled tolerance regimes, OCCT adds the user-facing articulation of fuzzy Booleans, enabling practitioners to choose robustness modes that match their data quality.

BRL‑CAD as a robustness anchor

Even as B‑rep kernels dominate mainstream CAD, BRL‑CAD remains an instructive anchor. Its ray-based CSG evaluation sidesteps many B‑rep fragilities by classifying space directly instead of constructing and stitching explicit boundaries during Booleans. In workflows where verification of mass properties, penetrations, or line‑of‑sight calculations matter, this approach provides resilient answers without the parade of slivers and near‑coincident trims that haunt NURBS-based pipelines. Moreover, the BRL‑CAD community has long cultivated regression practices and stable semantics for regularized set operations, making it a living reference against which B‑rep kernels can check results conceptually, if not numerically.

The coexistence of these paradigms is healthy. It reminds the industry that there is more than one way to achieve robust classification and that certain tasks—like ballistic analysis, ray-based verification, and visibility—are naturally aligned with CSG-first architectures. As hybrid CAD/CAE pipelines expand, expect to see more cross-pollination: B‑rep models used for drafting and surfacing, CSG or volumetric evaluations used for verification and manufacturing preparation, and mesh-level exact Booleans used for fabrication checks.

Adjacent domains: CAE, additive, and testing culture

Beyond classical CAD, the ripples of Boolean reliability are felt in simulation, fabrication, and software operations. In CAE, mesh generators routinely stumble on the artifacts of shaky Booleans: non-manifold edges, self-intersections, and microscopic faces that bust element quality metrics. The result is that geometry cleanup—once an ad hoc step—is now a standard pre‑FEA practice, often automated by scripts that detect and repair slivers, close small gaps, and remesh with feature-sensitive constraints. In additive manufacturing, where watertightness and manifoldness are non-negotiable, exact mesh Booleans have surged. Tools like OpenSCAD, powered by CGAL’s exact predicates and arrangements, demonstrated to a broad audience that deterministic operations on polygonal models are both feasible and valuable for fabrication. Research toolkits, including libigl-inspired predicates and robust winding-number classification, extended these benefits across custom workflows.

Equally important is the enterprise culture around robustness. Major kernel providers—including Siemens for Parasolid, Dassault for CGM, Autodesk for ShapeManager, and the OCCT community—maintain vast regression suites, nightly continuous integration, and telemetry feedback loops. Cloud-born platforms such as Onshape harness anonymized failure analytics to find, cluster, and fix corner cases at a scale previously impossible. Robustness is thus no longer just a feature of code; it is a property of the organization’s test data, its feedback apparatus, and its willingness to prioritize correctness even when it complicates short-term performance goals. This cultural shift is one reason Booleans have become less headline-prone over the last decade, despite rising model complexity and scale.

Conclusion

Boolean robustness as a socio‑technical alignment

The central lesson of the last forty years is that Boolean robustness is not solely a numerical victory or a topological triumph; it is a socio‑technical alignment. Kernels must balance floating‑point realities with exactness where it counts, encode topological invariants faithfully, and expose tolerance policies that are both principled and practical. Vendors must invest in regression infrastructure and telemetry so that real-world corner cases drive improvements, not just lab contrivances. And practitioners must adopt workflows—sew, heal, imprint—that recognize messy inputs as a norm, not a failure. When these pieces align, Booleans fade into the background as the reliable utility they were always meant to be.

A durable recipe, not a silver bullet

There is no one algorithm that “solves” Booleans. The durable recipe blends concepts, numerics, and plumbing: regularized set operations to guarantee meaningful outputs; exact/filtered predicates and adaptive precision to keep decisions honest; and tolerant modeling with documented healing to corral imperfect data into consistent B‑reps. For polyhedral worlds, arrangements and Nef polyhedra provide exactness with predictable performance tradeoffs. For NURBS-heavy models, hybrid strategies keep interactivity high while guarding against degeneracy. Regression suites and CI ensure that each improvement endures. The craft lies in staging these components so that speed and stability coexist, and in exposing just enough control for experts to tune behavior without overwhelming casual users.

Enduring tradeoffs and the near future

Some tradeoffs will remain. Exactness carries a cost; tolerant modeling can obscure small truths; NURBS B‑reps and polyhedral backstops must be bridged carefully to avoid semantic drift. Yet the trajectory is encouraging. Expect wider adoption of formalized kernel components inspired by CGAL, GPU-accelerated intersection kernels that still respect exact predicates, richer telemetry and CI corpora that surface rare degeneracies quickly, and tighter CAD–CAE–AM integration so that the same classification truths flow uninterrupted from design to simulation to fabrication. If the industry continues to pair mathematical humility with engineering discipline, Boolean operations will keep receding from drama to dependability—precisely where they belong.

Also in Design News

Cinema 4D Tip: Cinema 4D Parametric Primitive Blockout Workflow

February 20, 2026 2 min read

Read More

Revit Tip: Align linked Revit models using Shared Coordinates

February 20, 2026 2 min read

Read More

V-Ray Tip: V-Ray MultiMatte: Compact RGB ID Masks for Precise Compositing

February 20, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …