Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History:

December 10, 2025 13 min read

Introduction

Context and scope

The last six decades of architecture, engineering, and construction software trace a remarkable evolution from plotted lines to object-based BIM and, now, to connected, sensor-informed digital twins. This article follows that arc with a focus on core technologies, influential companies and people, and the standards and delivery models that turned niche drafting tools into the backbone of global AEC. We will examine how mainframes gave way to PCs; how virtual building concepts hardened into parametric modeling; how interoperability matured from file exchange to shared semantics; and how construction sites and operations joined the model loop through reality capture, IoT, and asset-centric data. Along the way, names like Intergraph, Calma, IBM/Dassault, Autodesk, Bentley, Graphisoft, Nemetschek, Tekla, Trimble, and buildingSMART recur—each contributing critical pieces across design authoring, coordination, fabrication, and operations. The through-line is the persistent effort to encode building intent in reusable, computable structures—first as layers and blocks, then as walls and ducts, later as schedules and costs, and now as streaming telemetry and lifecycle performance. The result is a discipline that increasingly treats the model as a contract of meaning, not just a picture—enabled by bidirectional associativity, neutral schemas, collaboration protocols, and cloud-based CDEs that turn models into living systems of record.

From drafting boards to object-based BIM: the AEC software arc

Early digitization and 2D democratization (1960s–1980s)

In the 1960s–1970s, AEC digitization leaned on mainframe and minicomputer CAD, when vector displays, pen plotters, and digitizers were the norm. Intergraph’s IGDS (Interactive Graphics Design System), guided by co-founder Jim Meadlock, put plant design and civil drafting on DEC VAX-class hardware, while Calma’s GDS terminals proliferated across engineering offices before the company passed through General Electric to Prime Computer. CADAM—born at Lockheed for aerospace—moved to IBM and later Dassault Systèmes, bringing industrial-grade drawing discipline that influenced building workflows even if AEC geometry lagged mechanical in rigor. Command-line interfaces, layers, and symbology conventions formalized production drawing logic, and batch plotting enforced document control before the term existed. Then, in 1982, Autodesk’s AutoCAD—co-founded by John Walker—shifted the center of gravity to commodity PCs, spreading 2D drafting across small and mid-sized firms. Bentley Systems followed with MicroStation (1987), founded by brothers Keith and Barry Bentley, emerging from IGDS roots and popular with infrastructure owners tied to DGN. The impact of these PC-era tools was profound: they normalized digital layering, XREFs/attach references, and scalable plotting in an affordable footprint. That democratization codified drafting culture in bits, set expectations for deliverable fidelity, and created the DWG/DGN dual heritage that still anchors countless archives and asset portfolios.

- Intergraph IGDS, Calma GDS, and CADAM established digital drawing discipline on high-end hardware.

- AutoCAD and MicroStation carried 2D drafting to the desktop, amplifying adoption and standardizing digital deliverables.

- Layering, XREFs/attachments, and plotting pipelines became the lingua franca of computer-aided drafting culture.

Toward building “objects” (late 1980s–1990s)

By the late 1980s, ambitious teams began encoding semantics about building elements rather than mere lines. Graphisoft, led by Gábor Bojár in Budapest, released ArchiCAD (1987), introducing “Virtual Building” concepts on PCs—walls, slabs, doors, windows, and schedules that coexisted with 2D views. Nemetschek’s Allplan advanced similar ideas in Germany, while Bentley’s TriForma layered object-based constructs onto MicroStation, linking 3D forms to parametric properties. Crucially, these platforms taught designers to think in terms of systems: a wall knew its thickness, composite structure, and materials; windows cut openings and drove quantity takeoffs; model views synchronized with documentation. Meanwhile, architecture’s most complex geometry found a different entry point. Frank Gehry’s practice harnessed CATIA’s parametric and NURBS capabilities (originally aerospace-grade) to tame freeform surfaces and coordination, culminating in the spin-out of Gehry Technologies. Under CTO Dennis R. Shelden, Gehry Technologies packaged these methods as Digital Project, adapting Dassault Systèmes’ CATIA V5 to architectural workflows with tailored feature trees, shop drawing extraction, and curvature analysis. The cross-pollination was catalytic: building design imported constraints and associativity from mechanical CAD, while AEC tools absorbed the lesson that parameters, not polylines, must describe intent. That shift set the stage for BIM to become an industry category rather than a collection of clever add-ons.

- ArchiCAD and Allplan normalized walls, slabs, and openings as first-class data-rich objects.

- Bentley TriForma connected MicroStation’s geometry with parametric building constructs.

- Gehry Technologies’ Digital Project bridged CATIA’s parametrics into architectural modeling for complex forms.

Parametric building modeling becomes mainstream (late 1990s–2000s)

The late 1990s brought a decisive turn with Revit, founded in 1997 by Leonid Raiz and Irwin Jungreis—veterans of parametric modeling at PTC. Revit’s hallmark—bidirectional associativity—ensured that any change to a plan, section, schedule, or object “family” propagated across the model, making drawings views of a single source of truth rather than separate files. Autodesk’s 2002 acquisition provided scale, and the family ecosystem catalyzed libraries from manufacturers. Parallel advances in structures and fabrication deepened BIM’s value. Tekla Structures (evolved from Xsteel) brought model-based steel and concrete detailing to the fore, enhancing constructability and shop accuracy; its later integration under Trimble connected design, surveying, and fabrication. Early MEP object systems expanded scope: Revit MEP integrated ducts, piping, and electrical systems with engineering calculations and clash mitigation, while Finland’s MagiCAD (from Progman, later part of Glodon) delivered richly parameterized HVAC and electrical catalogs across AutoCAD and Revit ecosystems. Together, these tools drew designers, engineers, and fabricators into a shared model context, making coordination predictable and quantities trustworthy. The era’s lesson: when objects encode both geometry and behavior—connection rules, load paths, flow constraints—the model naturally becomes the backbone of design and preconstruction, enabling a clearer handoff to downstream manufacturing and installation.

- Revit introduced a unified, associative model with extensible “families.”

- Tekla Structures tightened the design–fabrication link for steel and concrete.

- MEP object systems (Revit MEP, MagiCAD) extended BIM’s reach into building services engineering.

Standards, interoperability, and delivery: from files to federated models

File formats and model exchange

Interoperability has always trailed ambition in AEC. DWG (Autodesk) and DGN (Bentley) defined production drawing ecosystems, with DXF playing emissary between them. IGES, created in 1979 for mechanical data exchange, carried surfaces, curves, and solids reasonably well but proved ill-suited to the rich, semantic assemblies of buildings—where a “door” is more than boundary geometry. In the mid-1990s, the International Alliance for Interoperability—later buildingSMART—began crafting the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC), now standardized as ISO 16739. Champions like Patrick MacLeamy (then at HOK) pushed IFC beyond an academic exercise into a neutral, extensible schema that captures elements, relationships, and processes. Equally important, buildingSMART introduced BCF (BIM Collaboration Format), a lightweight, tool-agnostic way to exchange viewpoints, comments, and issue statuses without duplicating geometry. Together, IFC and BCF became the lingua franca for model federation across authoring tools and specialty platforms such as Solibri, Navisworks, and Revizto. The real advance was semantic: exchange moved from “what does this polyline approximate?” to “what is this thing, who owns it, and how does it relate to others?” That shift underwrites open semantics, auditability, and more faithful long-term archiving.

- DWG/DGN/DXF anchor legacy and ongoing 2D/3D production workflows.

- IFC (ISO 16739) provides a neutral schema for building and infrastructure semantics.

- BCF enables cross-tool issue tracking without duplicating geometry payloads.

Process standards and mandates

Technical schemas alone do not ensure reliable delivery. The UK’s BIM Level 2 mandate (2016) operationalized model-based collaboration by standardizing roles, information exchanges, and deliverables. PAS 1192 and BS 1192 concepts matured into the ISO 19650 series, which formalized the Common Data Environment (CDE), information containers, naming conventions, and responsibility matrices from concept to operations. COBie—pioneered by Bill East of the US Army Corps of Engineers—focused on structured handover data, specifying equipment, spaces, systems, and attributes needed by facility managers. As owner-operators—from healthcare to higher education—began to require COBie or equivalent asset data, project teams were forced to plan information production, not just drawing sets. This alignment of process and data fostered predictable exchanges between consultants, contractors, and operators and clarified the purpose of models at each stage. The upshot is that BIM matured as much through governance as technology: defining information requirements, acceptance criteria, and provenance raised trust and made “BIM as deliverable” viable in procurement and contracts.

- ISO 19650 codifies lifecycle information management and CDE practices.

- COBie structures handover data to serve operations and maintenance needs.

- Mandates shift focus from file drops to managed, role-based information flows.

Federation, coordination, and 4D/5D

Model federation turned multi-author models into a coordinated whole. Navisworks—originating with UK-based NavisWorks Ltd. and acquired by Autodesk—popularized aggregated model viewing and clash detection at scale, while Solibri Model Checker (from Finnish firm Solibri, now part of Nemetschek) emphasized rule-based validation and constructability checks. Time and cost dimensions followed. Synchro Software, acquired by Bentley in 2018, brought robust 4D scheduling that linked tasks to model components and absorbed data from Primavera P6 and Microsoft Project; Navisworks’ Timeliner offered related capabilities integrated with Autodesk ecosystems. In 5D, Graphisoft Constructor’s early ideas evolved under Vico Software into Vico Office, later acquired by Trimble, seeding model-based estimating practices that linked quantities, assemblies, and costs. Together, these advances reframed coordination from ad-hoc file comparison to persistent, issue-tracked, multi-dimensional planning. They also nudged teams from “clash hunting” toward means-and-methods simulation, prefabrication planning, and production control—connecting design intent to sequences, logistics, and budgets in one federated context.

- Clash and rule-based checks: Navisworks and Solibri establish coordination discipline.

- 4D: Synchro and Timeliner connect schedules to model elements for visual planning.

- 5D: Vico Office popularizes model-driven quantity takeoff and cost linkage.

Open ecosystems and bridges

The modern AEC stack blends commercial platforms with open-source tooling and cloud data hubs. IfcOpenShell (initiated by Thomas Krijnen) enables robust IFC parsing and geometry processing; BlenderBIM extends Blender with BIM authoring and IFC workflows; and xBIM (originating from UK academia and industry collaboration) powers IFC-centric applications in .NET environments. On the data movement front, Speckle—sparked by Dimitrie Stefanescu and Matteo Cominetti—implements a lightweight, open data exchange and versioning layer that bridges authoring tools and web services with granular object histories. Meanwhile, platform vendors pursue distinct CDE and “digital thread” strategies: Nemetschek champions OpenBIM through multi-brand offerings (Allplan, Archicad, Solibri) and integrations; Trimble connects Tekla, SketchUp, and Trimble Connect (whose roots trace to Gehry Technologies’ GTeam) to field hardware and scanning; Bentley couples ProjectWise with the iTwin platform for model federation, analytics, and APIs; Autodesk aligns Design/Docs/Build within Autodesk Construction Cloud to cover authoring through site workflows. The common denominator is API-first connectivity, commit histories, and model differencing—plumbing that turns files into federated, queryable datasets.

- IfcOpenShell, BlenderBIM, and xBIM lower barriers to IFC-centric development.

- Speckle enables evented, code-first model exchange on the web.

- Vendor CDE strategies converge on APIs, version control, and OpenBIM commitments.

From BIM to integrated construction digital twins: site, sensors, and operations

Reality capture and field digitization

As BIM matured, bringing real-world conditions into models became essential. Terrestrial laser scanners from Leica/Hexagon and FARO, alongside mobile LiDAR, produced dense point clouds for accurate as-built capture. Photogrammetry joined in: Autodesk ReCap streamlined registration and cleanup for designers, while Bentley’s ContextCapture—born from the Acute3D acquisition—generated reality meshes from extensive photo sets. Drones from DJI put aerial capture within reach, and platforms such as Propeller Aero simplified ground control, processing, and progress surface comparisons. Together, these tools reduced the friction between field measurement and model validation, enabling tolerance checks, early detection of installation drift, and verification of excavation quantities. Equally transformative, 360-degree photo platforms—OpenSpace (led by Jeevan Kalanithi), HoloBuilder (later acquired by FARO), and Buildots—applied AI to align imagery with BIM, automating progress quantification and QA/QC. The model ceased to be just a reference; it became the baseline to which reality is continuously compared, quantifying variance and informing pay applications, schedules, and rework decisions in near real-time.

- LiDAR and photogrammetry anchor accurate as-built and terrain modeling.

- Reality meshes provide visually rich, metrically reliable site context.

- AI-assisted progress capture compares site conditions to BIM for objective verification.

Connected construction platforms

Cloud-driven collaboration pulled authoring, coordination, and field execution under unified umbrellas. Autodesk Construction Cloud (and its predecessor BIM 360) wove submittals, RFIs, document control, model coordination, and field checklists into one subscription, backed by Forge/APS APIs. Trimble Connect, drawing lineage from Gehry Technologies’ GTeam, emphasized model-centric sharing that spans SketchUp, Tekla, and survey robotics, tying desktops to robotic total stations and scanners. Bentley’s ProjectWise paired with the iTwin platform extended managed document workflows into analytics, change visualization, and IoT overlays. Nemetschek’s Allplan Bimplus and the emerging dTwin consolidate multi-brand model coordination and operations data. In parallel, VDC methodologies championed by Stanford’s CIFE—led by Martin Fischer and John Kunz—helped teams translate design intent into means and methods, turning models into production plans. The result is a connected construction fabric where design changes ripple to field tasks, clashes escalate as issues, and installation data flows back for as-builts—reducing latency and making accountability visible through timestamps and audit trails.

- Unified platforms centralize models, issues, and documents with role-based access.

- APIs and connectors bridge authoring tools with field hardware and analytics.

- VDC practices align models with production planning and installation workflows.

Operations, asset twins, and semantics

Digital twins extend BIM into operations by anchoring assets in a semantic, time-aware model. Autodesk Tandem aims to curate design and construction data into operations-ready asset twins; Bentley’s iTwin Experience visualizes federated models with live data bindings; Trimble’s WorksOS targets civil works production control, while Trimble’s Cityworks supports city-scale asset management. These platforms align with the UK’s Gemini Principles (from the Centre for Digital Built Britain), emphasizing purpose, trust, and function for connected data environments, and draw guidance from the Digital Twin Consortium’s frameworks. Integrations with building automation bring stateful telemetry into the model: BACnet exposes BMS points; Project Haystack tags normalize equipment and sensor semantics; and Brick schema describes building systems for interoperable analytics. Layering predictive maintenance atop as-built twins allows teams to tie work orders, fault detection, and performance baselining directly to modeled systems. The twin thus becomes the substrate for energy tuning, space optimization, and long-term capital planning—grounded in traceable provenance back to design decisions and field changes.

- Asset-centric twins connect models to live operational data and work history.

- Semantic tagging (Haystack, Brick) and BACnet integrations enable cross-system analytics.

- Industry frameworks (Gemini Principles, DTC) guide trustworthy, purpose-driven twin deployments.

Sustainability and performance loops

Closing the loop between models and performance is imperative for carbon and energy goals. Life cycle assessment platforms like One Click LCA (founded by Panu Pasanen) and EC3 (by Building Transparency) leverage BIM quantities and product metadata to compute embodied carbon, steer specifications, and benchmark against Environmental Product Declarations. On the operational side, EnergyPlus—backed by the US DOE—and NREL’s OpenStudio connect calibrated models to simulation engines, while IESVE provides integrated loads, HVAC, and comfort analyses; Radiance, originally by Greg Ward, remains a gold standard for daylighting and glare. When linked to BIM, these tools reduce data re-entry, enabling rapid scenario testing and sensitivity analyses that consider both design intent and constructability. The emerging practice is a performance feedback loop: early-stage massing connects to target EUI and embodied carbon dashboards; detailed design aligns systems with control sequences; turnover packages map commissioning points to modeled assets; and operational analytics validate outcomes against targets. By embedding cost and carbon as co-equal metrics, teams can negotiate trade-offs transparently, from structural schemes to envelope assemblies and MEP selections.

- BIM-linked LCA quantifies embodied impacts early enough to influence design.

- Energy and daylight simulations inform both design choices and operating strategies.

- Feedback loops align specification, commissioning, and operations with sustainability goals.

Conclusion

Trajectory

The AEC software journey progressed from digitized lines to object-rich BIM and now to connected, living twins that span design, construction, and operations. Mainframe and minicomputer CAD imposed discipline on drawings; PC-era tools democratized 2D; object-based systems taught models to “know” what they represent; parametrics normalized change propagation; federation and coordination reframed delivery; and cloud platforms stitched sites and sensors into the digital thread. Each era layered new semantics and broader participation, raising expectations for fidelity, traceability, and collaboration. Today, models are no longer endpoints but waypoints in a data lifecycle—shaped by open schemas, governed in CDEs, animated by schedule and cost, verified against reality capture, and enriched by IoT during operations. The destination is not a single monolithic model but an ecosystem of synchronized views—authoring, coordination, estimating, scheduling, commissioning, and maintenance—bound by identity, provenance, and purpose. The industry’s arc thus bends toward continuously learning systems where design intent, production strategy, and performance outcomes are inseparable and mutually reinforcing.

- From drafting to BIM to twins, the through-line is increasing semantic richness and lifecycle continuity.

- Federated, API-first platforms replace file drops with shared, queryable data.

- Models evolve into operational assets with measurable, managed outcomes.

Lessons learned

Several themes stand out. Interoperability is not only about importing geometry but about preserving meaning—types, relationships, and responsibilities. IFC and BCF matter because they encode open semantics and discussion context that survive tool boundaries, enabling audits, automation, and long-term utility. Process frameworks (ISO 19650) and the CDE concept are as critical as authoring capabilities: without clear information requirements, naming, and approvals, coordination devolves into chaos regardless of software power. Traceable provenance—who changed what, when, and why—builds trust across disciplines and contractual interfaces. Finally, the value of BIM compounds when linked to downstream uses: fabrication, logistics, commissioning, and operations. Treating data as an asset, with gap analyses and acceptance criteria, aligns teams on outcomes rather than deliverable formats. In short, semantics, governance, and shared context are the multipliers that turn clever modeling into dependable delivery and durable institutional knowledge.

- IFC/BCF safeguard meaning and issues across tools and time.

- ISO 19650-aligned CDEs create dependable information supply chains.

- Outcome-driven information requirements connect design to construction and operations value.

Ongoing challenges

Significant hurdles remain. Data governance and long-term stewardship are uneven: archives mix DWG/DGN, proprietary BIM, and partial IFC, with unclear retention of metadata and identities over decades. Model fidelity versus effort is a perpetual tension on fast-moving jobsites; teams must balance LOD/LOI with changing scopes, vendor substitutions, and prefabrication realities. Contracting models and liability are still adapting to model-centric delivery; Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) and design–build encourage collaboration but require clarity on model purpose, reliance, and version of record to avoid disputes. Cultural gaps persist between office and field: authoring expertise does not automatically translate to installable, sequenced models; conversely, field insights are under-captured in design updates. Finally, cybersecurity and access control grow more complex as twins integrate BAS/BMS, work orders, and SCADA data. Addressing these challenges requires principled information strategies, role-based permissions, structured change logs, and training that treats data and models as shared, high-stakes infrastructure.

- Stewardship: assure identity, provenance, and readability over decades, not project phases.

- Scope vs. effort: calibrate LOD/LOI to real decisions and prefabrication needs.

- Contracts and risk: define reliance and responsibilities for model-centric delivery.

- Skills and culture: bridge authoring, coordination, and field execution fluency.

What’s next

The near future will intensify automation, integration, and feedback. AI-assisted model QA and code checking—seen in Solibri’s rule sets and emerging platforms like UpCodes—will expand into explainable, jurisdiction-aware assessments tied to submittals and permitting. Generative space planning tools such as TestFit will couple feasibility with live cost and carbon targets, making early decisions performance-informed. GIS–BIM fusion will accelerate as Esri ArcGIS, OGC CityGML, and IFC 4.3 converge for linear infrastructure, enabling city-scale twins with parcel, utility, mobility, and resilience layers. On site, robotic layout, autonomous scanning, and reality-to-model updates will tighten the loop from design to installation and verification; expect model deltas to post automatically to CDEs with confidence scoring. In operations, closed-loop telemetry will feed back into design handbooks: fault patterns, occupancy analytics, and energy signatures will update templates and families so that future projects start smarter. The strategic imperative remains: evolve from drawings to data products that are queryable, governable, and continuously improved—so every project, asset, and city learns from the last.

- AI elevates model checking, permitting, and early-stage synthesis tied to cost/carbon.

- GIS–BIM integration enables resilient, city-scale digital twins across domains.

- Automation on site and telemetry in operations close the loop for continuous improvement.

Also in Design News

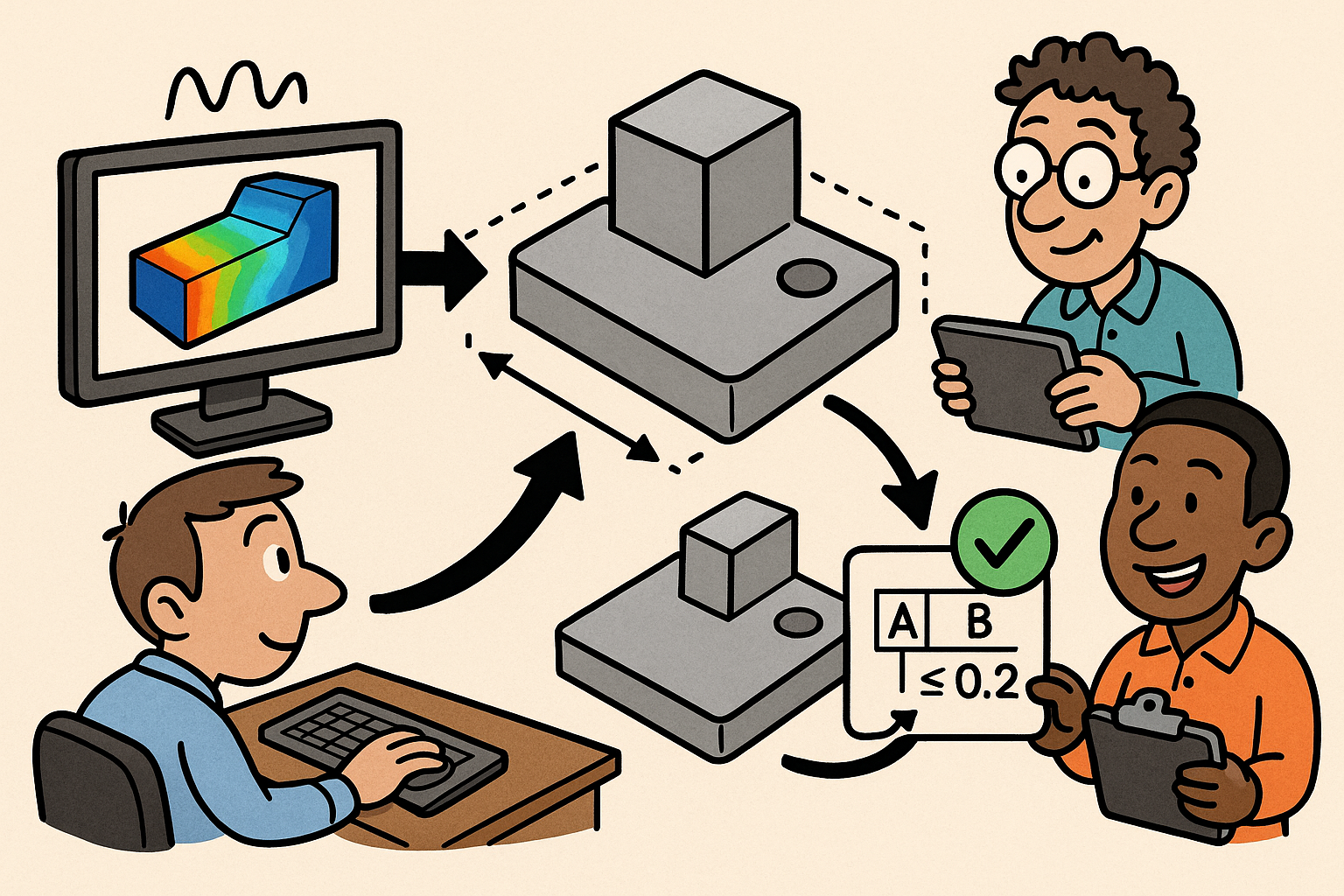

Simulation-Driven Automated Tolerancing for Capability-Aware GD&T

December 10, 2025 12 min read

Read More

Rhino 3D Tip: HDRI Workflow for Realistic Lighting and Fast Look‑Dev in Rhino

December 09, 2025 2 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Controlled Chamfers and Edge Weighting for Consistent Subdivision Bevels

December 09, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …