Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

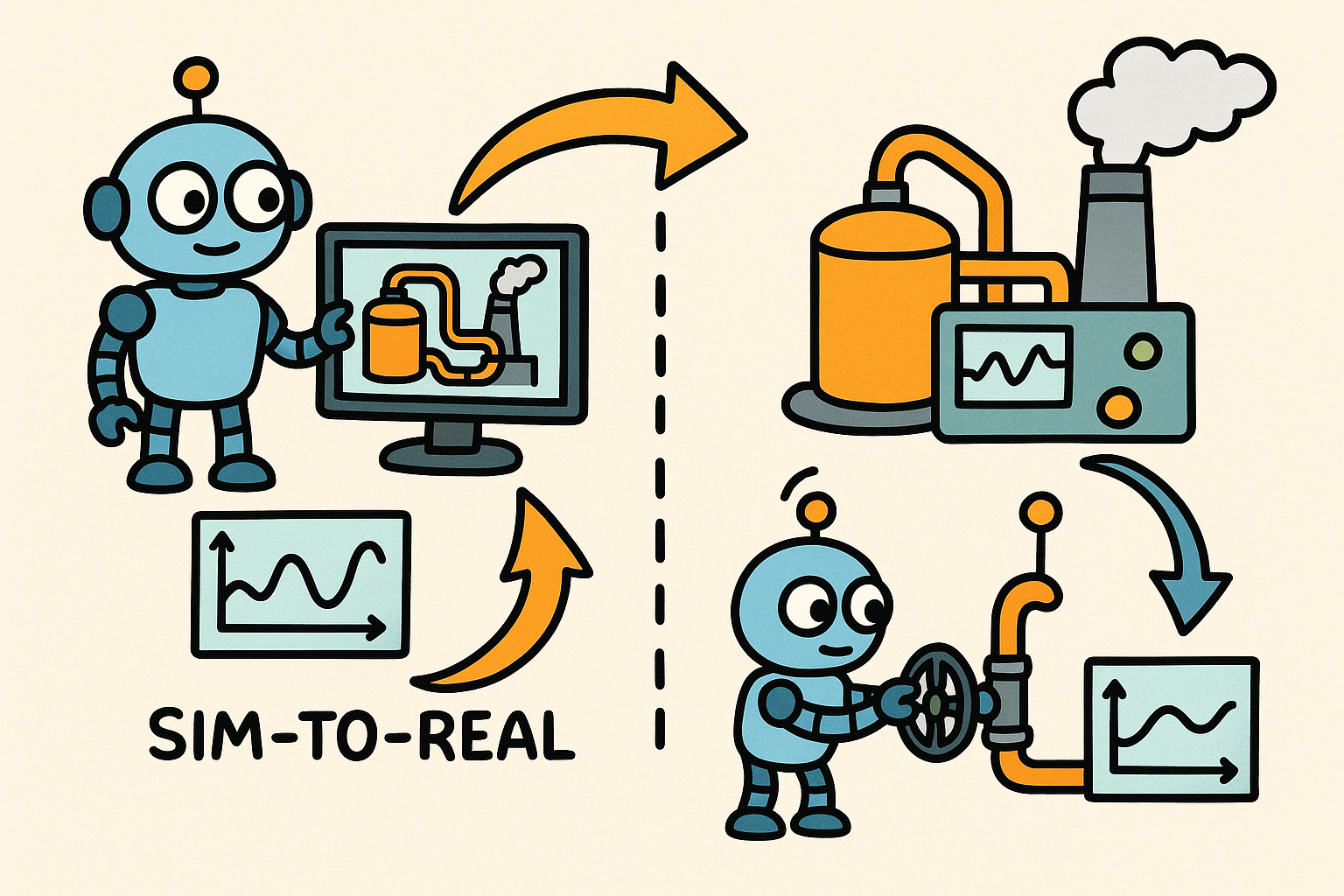

Sim-to-Real Transfer for Closed-Loop Process Calibration and Control

December 29, 2025 12 min read

Why Sim-to-Real Transfer Matters for Process Calibration and Control

Closing the Loop: Definition and Scope

In modern manufacturing, sim-to-real transfer describes the disciplined practice of using high-fidelity virtual models to rapidly calibrate and continuously control physical processes. The aim is not merely to forecast outcomes, but to close the loop—to drive controllers and setpoints from models that learn from real sensor data in near real time. In this framing, simulation is no longer a one-off design-time artifact; it becomes an active, adaptive twin that tunes parameters, infers hidden states, and guards quality as materials, machines, and ambient conditions drift. When executed well, sim-to-real builds a shared language across design, manufacturing engineering, quality, and operations, aligning the CAD-defined intent, CAM strategies, process physics, and machine controllers around a living source of truth. Critically, it enables auto-calibration of boundary and material parameters, resilient control policies under uncertainty, and quick identification of off-nominal behavior. The loop runs across design phases—parameter exploration, virtual commissioning, and PPAP readiness—and extends into production with shadow-mode validation, guarded rollout, and on-edge adaptation. To operationalize it, teams formalize assumptions, quantify uncertainty, and define trust regions where model-based control is allowed to act. The result is a production system that can intentionally leverage simulation while being grounded by telemetry, so that every scan path, spindle speed, or pack/hold segment is chosen not by static heuristics, but by a continuously learning and verifiably safe twin.

- Virtual models inform initial parameterization and control structure.

- Real sensor streams calibrate unknowns and detect drift in-flight.

- Guarded control enforces safety, quality, and compliance constraints.

Business Impact in Quantifiable Terms

The economic rationale for sim-to-real transfer is straightforward: compress ramp-up, de-risk PPAP, improve capability, and minimize waste. By grounding process windows in calibrated physics complemented by learned residuals, teams reach stable operation with fewer trial builds and shorter tuning loops. That means earlier revenue capture and lower working capital exposure. On quality, tighter control of thermal histories, bead geometry, chip load, cavity pressure, or blank draw profiles turns into higher first-pass yield and better Cp/Cpk. Energy and carbon per part fall when scans, toolpaths, and dwell times match the actual heat flow and mechanics of the current lot of powder, resin, billet, or sheet—not an idealized spec. Operationally, the twin becomes an instrumentation amplifier: it elevates the signal from your existing sensors, detects drift sooner, and prescribes targeted corrections rather than blunt, across-the-board slowdowns. The cost savings compound further when knowledge is versioned, reused, and rolled across families of parts. Even modest uplift in OEE coupled with reduced rework can fund the entire program. Executives gravitate to it because it translates directly into measurable improvements in cash, cost, compliance, and carbon for each SKU, not just a better on-screen plot. And crucially, it does so while preserving safety, thanks to explicit guardrails and human-in-the-loop handoffs during uncertain transitions.

- Faster process ramp-up and PPAP readiness through virtual commissioning and calibrated start points.

- Higher first-pass yield and capability indices (Cp/Cpk) via resilient control and real-time alignment.

- Reduced scrap and rework, lowering time-to-capability and inventory risk.

- Lower energy/carbon per part by matching inputs to actual thermal/mechanical response.

- OEE uplift through fewer stops, lower deviation rates, and quicker recovery from drift.

Target Processes and KPIs That Move the Needle

While the intuition is universal, the details of sim-to-real are process-specific. In laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), differentiable heat conduction and melt-pool models align to photodiode and IR data, steering power and speed layer-by-layer. In directed energy deposition (DED), bead height and dilution models inform travel speed and wire feed. In polymer AM, crystallization and warpage models tune chamber temperatures and cooling rates. CNC machining leverages stability lobes and tool wear models to avoid chatter while maximizing MRR. Injection molding hinges on PVT/viscosity identification and closed-loop pack/hold orchestrated by cavity pressure. Robotic welding uses vision to predict bead geometry and adjust torch angle live. Sheet forming draws on elastoplastic forming simulations coupled to rolling friction estimates. Composites—autoclave and out-of-autoclave—blend cure kinetics and thermal control to protect interlaminar quality. Across these, measurable KPIs tie the work to the P&L and ESG commitments. Teams should declare the scorecard upfront and instrument processes to compute it automatically, enabling rapid A/B comparisons and policy evolution without ambiguity. Doing so turns the twin into a daily management tool rather than a lab curiosity.

- Target processes: Metal AM (LPBF/DED), polymer AM, CNC machining, injection molding, robotic welding, sheet forming, composites (autoclave/OOA).

- Core KPIs: First-pass yield, TTc (time-to-capability), deviation rate, MTTD of drift, OEE uplift, energy/carbon per SKU.

- Supporting signals: melt-pool intensity, bead height/width, spindle vibration, cavity pressure/temperature, vision cues, strain or draw-in.

Technical Foundations of Sim-to-Real Transfer

Model Hierarchy, Hybridization, and Differentiable Simulators

Effective sim-to-real begins with a layered model strategy that balances interpretability, fidelity, and compute cost. At one end are white-box physics—thermo-fluid FEA/CFD, elastoplastic forming, tool–workpiece dynamics—anchored in conservation laws and material models. At the other end are black-box learners—Gaussian processes, deep networks, and tree ensembles—fast, expressive, and data-hungry. The sweet spot is often a gray-box: physics + learned residuals, where the simulator encodes known structure and a small model captures the discrepancy introduced by unmodeled physics, imperfect boundary conditions, or sensor bias. Crucially, emerging differentiable simulators enable gradient-based calibration and control: by exposing sensitivities of outputs to material parameters and boundary inputs, they turn parameter ID and policy optimization into well-posed optimization problems. Differentiable kernels can live inside CAM to refine toolpath features or inside MPC to compute gradients for constraint-aware updates. The practical rule is to keep the physics just rich enough to generalize and the learning small enough to prevent overfitting; instrumentation and UQ then decide how far you can trust the combination. When latency matters, distilled surrogates or reduced-order models approximate the differentiable core, with guarantees inside a defined trust region and graceful degradation when confidence drops.

- White-box: FEA/CFD/thermal, elastoplasticity, tool dynamics, cure kinetics.

- Gray-box: physics solvers with learned residuals or parameter fields.

- Black-box: surrogates (GPs, PINNs, neural operators) for rapid scoring.

- Autodiff: gradients for calibration, sensitivity, and control optimization.

System Identification, Calibration, and Discrepancy Modeling

Calibration is where models earn the right to influence the machine. Begin with priors on material constants, heat transfer coefficients, friction, or emissivity; then fuse sensor streams to infer posteriors. Bayesian parameter estimation (MCMC or variational) quantifies epistemic uncertainty, while expectation–maximization and Kalman/particle filters handle latent states in dynamic processes. For controllers requiring fast updates, moving-horizon estimation (MHE) balances recency with noise rejection. Equally important is explicit model discrepancy—for example, the Kennedy–O’Hagan framework—which captures the systematic gap between idealized physics and reality. This term can be learned as a function of state and inputs, becoming a corrective field that travels with the model to new parts and conditions. Practical setups schedule calibration at multiple scales: offline batch ID from designed experiments; online micro-calibrations as the process runs; and periodic re-baselining when materials, nozzles, or tools change. The deliverable is not a single number but a distribution over parameters and a bounded discrepancy function, each versioned with provenance. With these in hand, the controller can ask two vital questions in real time: “How sure am I?” and “How should I act given this uncertainty?”—and then allocate margin or trigger human review accordingly.

- Priors: material/thermal constants, friction, emissivity, sensor offsets.

- Estimators: MCMC, variational Bayes, EM, EKF/UKF, particle filters, MHE.

- Discrepancy: learned bias field with uncertainty; guards extrapolation.

- Outputs: parameter posteriors, confidence intervals, calibrated policies.

Mitigating the Domain Gap and Sensor Realism

Domain gaps arise because reality is messy: powders vary, tools wear, emissivity drifts, and sensors blur and lag. Robust sim-to-real anticipates this with training-time and run-time defenses. Domain randomization perturbs inputs (e.g., absorptivity, convection coefficients, fixture compliance) and sensor effects (noise, latency, blur, occlusion) so that learned policies prefer invariants. Transfer learning adapts models to scarce, high-signal real data, while adversarial feature alignment encourages embeddings that cannot distinguish sim from real. Explicit sensor modeling closes the loop between what the twin “sees” and what the camera, accelerometer, or pyrometer reports—including nonlinearity and saturation. Uncertainty-aware training propagates both aleatoric noise and epistemic model uncertainty into outputs, letting downstream controllers budget risk. The practical pattern is simple: simulate varied worlds, inject sensor realism, fine-tune with limited but curated real runs, and then validate in shadow mode before closing the loop. Investing in sensor calibration—spatial registration, emissivity charts, synchronization, and timestamp integrity—pays back many times over because it squeezes more truth out of the same hardware and defuses brittle policies that lean on artifacts rather than physics.

- Randomize: material lots, boundary conditions, fixture stiffness, ambient flow.

- Model sensors: noise spectra, latency distributions, blur kernels, occlusions.

- Adapt: fine-tune on small, diverse real datasets; align features adversarially.

- Verify: synchronization, calibration targets, emissivity compensation, ground truths.

Uncertainty, Validation, and Safe Control With Online Adaptation

Trustworthy deployment requires uncertainty quantification, rigorous validation, and safety-first control. Separate aleatoric variability (intrinsic randomness) from epistemic uncertainty (knowledge gaps) to decide when to allocate margin or abstain. Conduct posterior predictive checks and adopt V&V thinking akin to ASME V&V 20 to assess credibility for the intended use. Define trust regions—subspaces of parts, materials, and conditions—where the model’s calibrated accuracy is proven, and implement guardrails that fall back to conservative policies outside them. On the control side, robust MPC with learned or differentiable models enforces state and input constraints under uncertainty, while safe RL with shields constrains exploration to certified envelopes. Online adaptation handles drift—tool wear, fouling, thermal creep, humidity—via on-edge updates of parameter posteriors and residual fields. Lightweight updates respect real-time budgets using incremental inference or low-rank corrections. The supervisory logic blends confidence, cost, and quality targets to pick actions that minimize expected loss. The system can also schedule recalibration, recommend maintenance, or request human override when uncertainty spikes. With this scaffolding, sim-to-real becomes a dependable copilot: vigilant, conservative when needed, and quick to exploit safe opportunities for speed and quality.

- Quantify: aleatoric vs epistemic; posterior predictive checks; VColl metrics.

- Constrain: hard constraints in MPC; shields and Lyapunov bounds in RL.

- Adapt: on-edge Bayesian updates; drift detection with MTTD targets.

- Escalate: human-in-the-loop and safe fallback outside trust regions.

Software Architecture and Workflow Integration in Design Tools

The Digital Thread Topology and Standards That Make It Flow

To move beyond demos, sim-to-real must ride a robust digital thread from design intent to machine actuation. Geometry and tolerances originate in CAD/MBD; manufacturability and toolpaths emerge in CAM; the simulation twin tracks physics and control logic; the MES/SCADA layer orchestrates execution; and the controller enforces constraints on the machine. Interoperability is non-negotiable: STEP AP242 and QIF carry semantic GD&T and PMI to downstream steps, preserving intent; OPC UA and MTConnect expose machine states, tags, and time-aligned signals; and ONNX enables model exchange across inference runtimes on edge and cloud. Identity, versioning, and provenance live in PLM so that every parameter set and policy can be traced to the exact part revision and calibration dataset. With this plumbing in place, twins can subscribe to machine telemetry, publish parameter updates, and annotate runs for review. Security and safety layers ensure that only authorized policies with valid signatures can command actuators. The payoff is a thread where physics and data can flow freely, yet safely, between design desks, simulation farms, and shop-floor controllers, enabling closed-loop manufacturability as a first-class citizen rather than an afterthought.

- Topology: CAD/MBD → CAM/toolpaths → simulation twin → MES/SCADA → controller.

- Standards: STEP AP242/QIF for intent; OPC UA/MTConnect for data; ONNX for models.

- Governance: PLM-based versioning, provenance, and access control with audit trails.

- Synchronization: time stamping, clock drift correction, and unit/coordinate consistency.

Data, Geometry Features, and Reusable Feature Stores

Closing the loop depends on a shared schema that binds design features to process knobs and sensor streams. Practical implementations compute geometric descriptors—wall thickness distributions, overhang angles, ribs, pockets, heat sinks, fillets, tool engagement maps—and bind them to local process parameters and expected sensor signals. These descriptors then feed a feature store where reusable geometry–process embeddings live across parts and materials. For example, the system can learn that a 1.2 mm vertical wall adjacent to a solid boss behaves like a heat sink in LPBF and adjust scan strategies accordingly, or that a pocket corner with a certain engagement history predicts chatter onset for a given toolholder. A well-designed store captures invariants across CAD variants and provides inputs to surrogates and controllers without bespoke data munging each time. It also standardizes labels, units, and confidence metadata so that quality and operations can compare apples to apples across programs. Combined with robust data access patterns, this yields agility: when a material lot changes, the twin evaluates exactly which features and process segments need retuning, rather than treating the part as a monolith.

- Geometry: thickness maps, curvature, overhang, ribs, bosses, fillets, chamfers.

- Process: scan spacing, power/speed, spindle/feed, pack/hold, travel angles.

- Sensors: photodiode intensity, IR temperature, accelerometer bands, cavity pressure.

- Embeddings: reusable vectors linking local geometry to process and sensor signatures.

Pipeline Patterns From Pre-Production to Orchestrated Deployment

The operational pipeline follows a repeatable pattern that scales from pilot cells to global fleets. In pre-production, teams run virtual DOE and parameter optimization through the twin, compressing the search space before metal or polymer is ever melted. Virtual commissioning primes controllers with safe initial policies and tests interlocks in a sandboxed environment. During production, the twin monitors live sensors, aligns to reality with continuous calibration, and proposes parameter nudges or path edits. Policy changes stage in shadow mode, scoring alternative actions without commanding actuators until confidence clears a threshold; A/B rollouts measure uplift against baseline. Orchestration spans cloud and edge: cloud simulation farms (Kubernetes with spot capacity) handle heavy analysis and retraining; edge compute executes real-time inference with ONNX Runtime or WASM to meet millisecond deadlines. Telemetry, decisions, and outcomes flow back for learning, with drift detectors scheduling recalibration or maintenance. By enforcing this pattern, organizations avoid the “hero project” trap, instead building a system that is observable, repeatable, and compliant by default.

- Pre-production: virtual DOE, optimization, virtual commissioning of control logic.

- Production: online monitoring, twin alignment, guarded policy rollout via shadow mode.

- Orchestration: cloud simulation farms (Kubernetes/spot) and edge inference (WASM/ONNX Runtime).

- Feedback: automated logging, drift detection, and schedule for re-calibration.

Integration Into Design Software and Process-Specific Snapshots

Design tools become more powerful when they surface process intelligence natively. CAD/CAM plugins can propose context-aware process windows and toolpath tweaks with confidence bands, flagging areas likely to warp, chatter, underfill, or burnish. Engineers can accept suggestions inline, generating a closed-loop parameter template that is automatically versioned with the part revision and recorded in PLM with full provenance. As the part moves to the floor, the same template tunes controllers in a traceable way. To illustrate the breadth of integration, consider a few process snapshots. In LPBF, a melt-pool twin calibrated with IR and photodiode streams adjusts power and scan speed per stripe to hit target solidification; the plugin visualizes expected densification and distortion. In injection molding, PVT and viscosity curves are identified from short shots and step tests; cavity pressure feedback drives MPC during pack/hold for dimension stability. CNC plugins estimate stability lobes from accelerometers and update spindle/feed to sidestep chatter while maximizing MRR. Robotic welding uses vision to forecast bead width/height and adapt travel speed and wire feed. Each scenario shares the same pattern: a calibrated twin, a guarded controller, and a design-native UI that puts confidence and consequences front and center.

- LPBF AM: IR/photodiode-calibrated melt-pool twin; layer-wise power/scan speed control.

- Injection molding: PVT/viscosity ID; cavity pressure-driven MPC for pack/hold.

- CNC: stability-lobe identification from accelerometers; adaptive spindle/feed to avoid chatter.

- Robotic welding: bead geometry prediction with vision; real-time travel speed and wire feed control.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways and a Practical Implementation Checklist

The throughline is clear: sim-to-real transfer elevates manufacturing from recipe following to model-guided, data-validated decision-making. When models and sensors co-evolve, organizations calibrate faster, control more robustly, and deliver consistent quality across materials, machines, and sites. The winning strategies rely on hybrid models that respect physics while learning what’s missing, explicit uncertainty quantification that informs when to act and when to defer, and guarded deployment patterns that invite confidence rather than demand faith. Success hinges on getting the foundations right—standards, schemas, telemetry, and governance—so that improvements compound rather than reset with each program. To help teams start, the following checklist maps the theory to action. Treat it as a living artifact in your PLM, revisited at each gate. Above all, remember that the goal is not perfect prediction but reliable control under uncertainty, with safety and human expertise integrated by design. With that mindset, your digital twins will stop being passive dashboards and start operating as active copilots that make better decisions, faster, with fewer surprises and smaller footprints.

- Define KPIs, trust regions, and interlocks; prioritize high-signal sensors first.

- Adopt hybrid modeling (physics + residual ML) with explicit discrepancy terms.

- Use posterior predictive checks and shadow mode to validate before closing the loop.

- Version models, parameters, and policies with full provenance in PLM.

- Monitor drift, track MTTD, and schedule re-calibration/maintenance proactively.

- Enforce safety constraints, signatures, and human-in-the-loop overrides at all times.

What’s Next for Design-Native Closed-Loop Manufacturability

The frontier is moving toward differentiable factory twins that span entire cells and lines: thermo-fluid-structure models composited with queueing and maintenance dynamics, all amenable to gradient-based optimization and robust control. Expect federated learning to stitch insights across sites without pooled raw data, preserving IP and privacy while accelerating convergence on robust residuals and discrepancy fields. Standards will mature toward twin APIs embedded directly in CAD/CAM/PLM, making closed-loop manufacturability checks as native as GD&T—complete with callable services for uncertainty, sensitivity, and feasibility queries. On the edge, slimmer runtimes will blend ONNX, WASM, and hardware acceleration to push millisecond decisions into tighter control loops. Traceability will extend to ethical and environmental claims, tying calibrated energy models and verified scrap rates to product declarations. As these capabilities normalize, design will increasingly specify not just geometric intent but control intent: acceptable risk, recovery strategies, and fallback modes captured as constraints that travel with the part. The organizations that win will be those that treat sim-to-real as a socio-technical system—tools and models co-designed with processes and people—and who invest in the boring but essential disciplines of data quality, provenance, and governance. Do that, and you’ll unlock a design-to-production pipeline where calibration is automatic, control is resilient, and quality is the default outcome, not a lucky one.

Also in Design News

Design Software History: Visualizing Engineering Intent: Feature Histories, Constraints, and Semantic PMI in CAD

December 29, 2025 16 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Cineware Best Practices for Cinema 4D to After Effects

December 29, 2025 2 min read

Read More

V-Ray Tip: V-Ray IPR Optimization for Faster Iteration and Reliable Final Renders

December 29, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …