Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

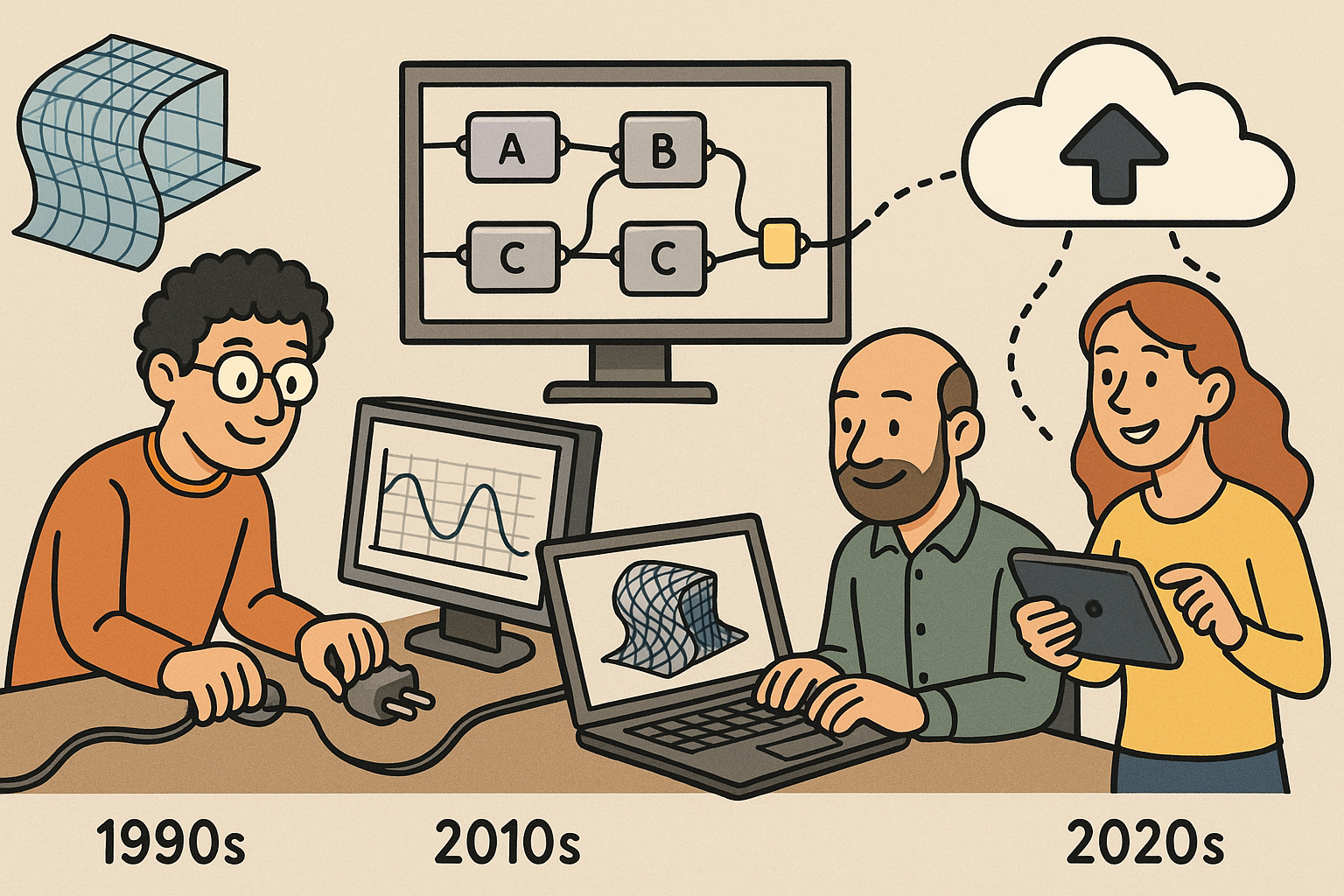

Design Software History: Parametric Platforms and Scripting Ecosystems in Architecture: From Plugins to Cloud-Native Design (1990s–2020s)

January 18, 2026 14 min read

Origins: parametric plugins and early scripting in architecture (1990s–2008)

Precedents in practice and research

By the late 1990s, forward-leaning architectural practices were converging on a common realization: freeform geometry was surpassing what conventional drafting and static surface modeling could manage. Gehry Technologies’ Digital Project—built on Dassault Systèmes’ CATIA V5—set the tone by operationalizing aircraft-grade surface definition and fabrication-aware assemblies inside architecture. What mattered was not just curvature, but the chain of custody from spline to shop drawing and on to CNC: Digital Project maintained surface class continuity, component hierarchies, and material tolerances, so teams could reason about skins, ribs, and secondary structure as parametrically related systems rather than isolated drawings. In tandem, studios like Greg Lynn FORM, early Zaha Hadid Architects, and groups at Foster + Partners tapped into animation tools—Maya MEL and 3ds MaxScript—to prototype behaviors such as growth, flow, and relaxation. Form•Z’s scripting further encouraged exploratory loops, where a designer could tweak variables and regenerate families of variants. Across these labs and offices, a language of associativity, constraint, and fabrication logic began to cohere. The goal was not simply to produce visually novel forms, but to encode how they were produced so that changes upstream reverberated downstream. This era did not yet universalize parametric modeling across the AEC industry, but it crystallized the central insight that complex geometry and production knowledge could live in the same model and move together through time.

- Digital Project operationalized associative assemblies atop CATIA V5’s robust NURBS kernel.

- Maya MEL and 3ds MaxScript enabled designers to treat form as an output of code-driven behaviors.

- Form•Z scripting bridged exploratory modeling with parameter tweaking and variant generation.

Bentley’s GenerativeComponents and the SmartGeometry nexus

Bentley Systems’ GenerativeComponents (GC), guided by Robert Aish, introduced architects and engineers to an explicitly parametric idiom embedded in design practice. GC made relationships first-class citizens: points, curves, and surfaces were not just shapes but nodes in a dependency network whose connections captured intent. Through the SmartGeometry community—coalescing around practitioners from Foster + Partners, Arup, and allied firms—GC’s ideas moved beyond software features to become a shared culture of constraint-driven geometry. The workshops emphasized hands-on exchange: encode a baseline rule set, test it against performance criteria, then alter inputs and regenerate the system. This iterative loop replaced one-off modeling feats with reproducible, discussable, and auditable patterns. GC’s exposure of parametric scopes—local rules inside larger assemblies—taught teams to think about how a façade panel relates to a bay, a bay to a façade strip, and that strip to a building’s structural rhythm. Meanwhile, Arup’s computational specialists helped align parametric modeling with analytical processes, creating channels between structural and environmental checks and the geometry that fed them. The result was an early blueprint for what would later become mainstream in AEC: model as process, not artifact; drawing as a view of a computation, not a frozen picture of a form.

- GC elevated constraints and relationships into the core authoring experience.

- SmartGeometry cultivated a practitioner-led pedagogy and community of practice.

- Foster + Partners and Arup demonstrated how design and analysis could be co-authored parametrically.

RhinoScript and the rise of Grasshopper

While GC matured inside the Bentley ecosystem, Robert McNeel & Associates catalyzed a different, more lightweight trajectory through Rhino. RhinoScript unlocked fast, scriptable access to NURBS modeling without the overhead of enterprise PLM systems. This mattered to small and mid-sized offices that needed agility: write a few lines of VBScript to lay out panels, generate curves, or extract fabrication geometry, then refine on the fly. The breakthrough, however, was David Rutten’s Grasshopper—initially released as “Explicit History” circa 2007–2008. Grasshopper translated parametrics into visual programming that designers could read at a glance: nodes and wires, data trees, sliders, and components embodying geometric and logical operations. The interface made dependency legible, while custom components and .NET/C# scripting opened escape hatches for deeper control. Suddenly, parametric thinking no longer required a background in CATIA or a specialized seat of GC. The community flourished around forums where users traded definitions, techniques, and emergent patterns—“data trees” became part of the designer’s vocabulary. Because Rhino was both precise and forgiving, teams could mix sketch-like exploration with manufacturing-grade detail, and Grasshopper’s graphs evolved from schematic studies to production pipelines. The center of gravity shifted: the average designer could build and iterate a parametric model without gatekeepers, accelerating diffusion across architecture schools and practices.

- RhinoScript lowered the threshold for scripting-driven modeling.

- Grasshopper introduced node-based logic with live, slider-driven feedback.

- Extensibility via .NET/C# embedded a continuum from no-code to full-code inside one environment.

Community catalysts: workshops, conferences, and a shared vocabulary

The early 2000s saw a dense mesh of events turning scattered experiments into a movement. SmartGeometry’s traveling workshops demystified complex workflows by pairing designers, engineers, and software developers at the same table; what happened in advanced practices on Tuesday became public method by Friday. ACADIA, with its papers and hands-on sessions, tightened the link between academic research and practice. Conference proceedings formalized how to document parametric intent, whether through dependency graphs, rule sets, or performance scripts, so that others could reproduce and critique them. Online forums and emerging repositories reinforced the pattern: share definitions, annotate dependencies, and situate computational work within clear problem statements. This era produced a shared vocabulary—associativity, fitness, rule-based systems—that felt native to both studios and schools. Crucially, it also recast authorship. Instead of monolithic models, teams assembled toolchains: a MEL script tuning constraints, a RhinoScript creating surface scaffolds, a Digital Project routine organizing panels. Knowledge spread horizontally through community-led iteration, not just vendor training. By 2008, with Grasshopper’s ascent and GC’s maturation, the discipline had a foundation robust enough to scale, yet flexible enough to accommodate local agendas and materials, setting the stage for the next decade’s ecosystem explosion.

- SmartGeometry moved techniques from expert silos into public practice.

- ACADIA codified methods through peer-reviewed dissemination and workshops.

- Forums and shared repositories normalized open exchange of scripts and models.

From plugins to scripting ecosystems: visual programming, BIM integration, and open toolchains (2009–2020)

Grasshopper’s ecosystem blossoms

After 2009, Grasshopper transformed from a powerful authoring tool into the nucleus of an entire ecosystem. David Rutten’s Galapagos component embedded evolutionary search, letting designers steer populations of solutions with single- or multi-objective fitness functions. Daniel Piker’s Kangaroo reframed geometry as an outcome of physics—tension nets, catenary chains, and material-aware relaxation—turning “form-finding” into a live, interactive simulation. Clemens Preisinger’s Karamba3D placed structural analysis in the same graph as geometry, so sections and support conditions could evolve alongside massing. Meanwhile, Mostapha Sadeghipour Roudsari, Chris Mackey, and a community of contributors built Ladybug Tools to bridge Grasshopper with Radiance, Daysim, EnergyPlus, and OpenStudio, enabling climate-informed daylight and energy modeling through parametric workflows. On the fabrication front, KUKA|prc by Johannes Braumann and Sigrid Brell-Cokcan translated robot programming into the design space, spurring a wave of CNC and robotics plugins that closed the loop from slider to toolpath. This growth was accelerated by Food4Rhino, which provided a distribution hub, versioning, and discoverability. Grasshopper became not just a canvas for geometry but a platform for computational craft, where analysis, optimization, and fabrication could be composed like sentences. As each plugin carved out a specialty and interoperated with others, the community learned to treat the graph itself as an integrated experiment, delivering performance-literate models without leaving the design environment.

- Galapagos normalized evolutionary search inside concept design.

- Kangaroo and Karamba3D integrated physics and structure with geometry.

- Ladybug Tools connected environmental engines to visual programming.

- KUKA|prc and related plugins linked parametric intent to machine code.

- Food4Rhino catalyzed distribution and discoverability across the ecosystem.

Autodesk’s BIM-centric track

In parallel, Autodesk advanced a BIM-centric route with Dynamo for Revit, initiated by Ian Keough and released as an open-source project. Dynamo brought visual programming into the heart of BIM, aligning parametric logic with Revit’s element-based database: walls, families, and parameters became nodes in the graph. Robert Aish’s DesignScript enriched this environment with a concise language blending associative programming and geometry semantics, making list processing and pattern-based reasoning accessible within Dynamo. Autodesk then packaged optimization and design-space exploration as “Generative Design in Revit,” evolving from Project Refinery to provide project teams with templated workflows for objectives, constraints, and tradeoffs. The shift was significant: instead of exporting geometry out of BIM for analysis and then reimporting, Dynamo co-located logic with documentation, schedules, and coordination datasets. While Grasshopper excelled in open-ended geometric exploration, Dynamo normalized parametric literacy at BIM scale, where stakeholders needed parameters tied to cost, procurement, and compliance. This split—Rhino/Grasshopper for geometry-centric prototyping; Revit/Dynamo for BIM-native parametrics—was less a competition than a complementary ecosystem. Together they taught firms to think in graphs, lists, and dependencies as the lingua franca of building information, enabling traceable design transformations directly connected to deliverables.

- Dynamo integrated parametric logic with Revit’s element graph and parameters.

- DesignScript offered a compact, associative language within visual programming.

- Generative Design in Revit operationalized optioneering for project teams.

Interop and “inside” workflows

By the late 2010s, the most consequential advances were not single tools but bridges. Rhino.Inside.Revit allowed Rhino and Grasshopper to run within Revit’s process space, fusing NURBS/SubD modeling with BIM parameters so designers could push curves into families, pull metadata back out, and synchronize updates across both worlds. Speckle, led by Speckle Systems, reimagined interoperability as cloud-native AEC data streaming, creating a versioned, schema-mappable substrate for geometry and attributes that moves between applications without brittle file exports. The Buildings and Habitats object Model (BHoM) introduced a shared, tool-agnostic object model, letting teams define cross-tool semantics for elements like panels, beams, and loads. Meanwhile, Rhino Compute and Hops exposed Grasshopper definitions as web services, enabling headless execution for batch processing, dashboards, and enterprise pipelines. Collectively, these steps reframed parametric models as services that could be orchestrated, tested, and scaled. Interop was no longer a last-mile export; it was a first-class design strategy. Firms began to treat definitions as assets stored in source control, executed in CI pipelines, and deployed to automation servers that watched repositories for changes—an early foreshadowing of AEC’s shift toward API-first design operations.

- Rhino.Inside.Revit fused geometric agility with BIM semantics.

- Speckle enabled versioned, streaming data exchange across tools.

- BHoM formalized cross-platform object definitions in AEC.

- Rhino Compute/Hops turned Grasshopper graphs into scalable services.

Beyond AEC’s borders: proceduralism and cloud composability

Outside standard architectural pipelines, SideFX Houdini gained traction for procedural urbanism, façade systems, and data-driven site synthesis—areas where its attribute-based modeling, VEX, and SOP networks excel. Houdini’s procedural paradigm resonated with architects already fluent in node graphs, while its ability to ingest GIS and simulation data made it a potent aggregator. On another front, Hypar—co-founded by Anthony Hauck and Ian Keough—proposed a marketplace of composable cloud functions for buildings, where systems like cores, floorplates, and MEP distributions could be authored as deterministic generators and assembled into full proposals. The attraction was not just speed, but governance: default standards and enterprise constraints could be encoded once and reused across projects, creating repeatability without stifling local variation. These platforms emphasized that generative systems need not be monolithic desktop files; they can be distributed services snapping together like APIs. The lesson fed back into AEC: whether via Houdini’s procedural arithmetic or Hypar’s function-driven composability, parametrics were evolving into a software architecture problem—dependencies, testing, and deployment—just as much as a modeling problem. This broadened the field’s imagination beyond plugins toward orchestrated assemblies of capabilities, executed wherever they make the most sense: desktop, server, or cloud.

- Houdini’s attribute-based modeling suited city-scale and façade logic.

- Hypar framed building systems as reusable, cloud-executed generators.

- Proceduralism and composability reframed design as software orchestration.

Core technologies, algorithms, and workflows that made it possible

Geometry and representation

Three representations underwrite most algorithmic design in AEC: NURBS, meshes, and SubD. NURBS remain the workhorse for precise freeform surfaces—continuity classes, exact arcs, and the ability to drive downstream CAM make them indispensable. Meshes dominate analysis and visualization, as their discretization aligns with finite element solvers, ray tracing, and GPU pipelines. SubD, notably expanded in Rhino 7, offers editable organic forms that can be subdivided smoothly while retaining edge control, a sweet spot between sculptability and precision. The design challenge is not choosing a single representation but hybridizing them intelligently: convert NURBS to meshes for analysis; wrap meshes into SubD for art-directed smoothing; then extract NURBS patches back where tolerances demand. Underneath, dataflow graphs maintain dependency tracking so that representational changes do not sever intent. Effective graphs scope parametric influence—local variances controlled by sliders, global invariants enforced by shared parameters—so that recomputation strategies stay predictable. As models scale, caching and partial recompute become crucial: update only the nodes affected by a parameter change, persist expensive analyses, and serialize intermediate states. Good parametric hygiene means treating geometry as the visible layer of a deeper data model, which carefully separates concerns: representation for making and seeing; topology for reasoning; and metadata for linking design to analysis and cost.

- NURBS provide accuracy and continuity for production-grade surfaces.

- Meshes align with solvers and visualization, enabling scalable analysis.

- SubD offers editable organic forms that can be rationalized when needed.

- Hybrid pipelines convert and validate across representations with intent preserved.

Solvers, optimization, and the role of learning

Constraint handling starts with geometric relations—parallelism, tangency, equal length—but quickly climbs to graph-based solvers coordinating hundreds of dependencies. Visual programming environments encode these relations declaratively: specify what must hold, let the solver figure out how. Optimization layers on top. Single-objective evolutionary search, popularized inside Grasshopper through Galapagos, explores design spaces by mutating inputs and selecting fitter offspring. Multi-objective methods weigh tradeoffs—daylight versus energy, structure versus mass—surfacing Pareto fronts that replace “the answer” with a set of defensible options. Crucially, optimization becomes most valuable when coupled to external engines: parametric models feed Karamba3D for structure, Radiance for daylight, or EnergyPlus via Honeybee for thermal performance, creating closed loops that elevate fitness from geometry-only proxies to measurable outcomes. Emerging machine learning links add acceleration: surrogate models approximate expensive simulations to speed exploration; clustering organizes result sets into interpretable families; early prediction narrows search regions before solvers run. These learning tools do not replace first-principles analysis; they wrap it, guiding attention and reducing computational cost. The maturation of optimization-aware design means teams can quantify tradeoffs earlier and more transparently, turning intuition into testable hypotheses and replacing hand-picked favorites with evidence-backed shortlists.

- Declarative constraints scale geometric intent across complex dependencies.

- Evolutionary and multi-objective methods provide robust exploration strategies.

- Coupling with structural, daylight, and energy engines grounds fitness in performance.

- Surrogate modeling and clustering help prioritize and interpret large design spaces.

Fabrication-aware computation and robotic toolchains

Parametric modeling matured when it met the shop floor. Kangaroo’s physics-based form-finding tuned geometry to material realities—fabric, cable, timber strip—so that minimal surfaces and tension systems emerged from simulated forces rather than ad hoc sculpting. On the production side, toolchains like KUKA|prc, HAL Robotics, and RoboDK integrations bridged from scripted geometry to robot motion, including kinematics, reachability, collision checking, and post-processing for specific controllers. The payoff was profound: a Grasshopper definition could bake geometry, lay out panel identifiers, compute toolpaths, and package code for machines—all while staying responsive to late-stage changes. Calibration routines, end-effector models, and IO triggers became parametric components too, capturing tacit shop knowledge. DFA/DFM considerations folded upstream: kerf, stock dimensions, and bend radii entered the design graph as parameters. This closed-loop approach reduced error and increased repeatability, since validation and fabrication lived in the same computational context. The role of the designer expanded into computational fabricator, orchestrating digital-physical feedback where fixtures, materials, and robots co-determined what the design could be. The result was not just faster production, but a more faithful translation of intent into matter, with less friction between geometry and making.

- Physics simulation matches form-finding to material and assembly logics.

- Robotic/CNC plugins translate parametric geometry into verified machine code.

- Manufacturing constraints become parameters within the design graph.

- Digital-physical feedback loops reduce error and amplify repeatability.

Software engineering practices in AEC

As graphs and codebases grew, AEC quietly adopted software engineering habits. Extensibility across Python, C#, and C++ let teams encapsulate complex operations into reusable components for Rhino/Grasshopper and Dynamo. COMPAS, driven by ETH Zurich’s Gramazio Kohler Research and the Block Research Group, provided a Python framework to standardize geometry processing, robotics, and structural form-finding across research and practice, with clear APIs and documentation. Source control moved from novelty to necessity: GitHub and GitLab tracked versions of definitions, scripts, and schemas, while pull requests institutionalized peer review of parametric logic. Package managers and registries improved distribution, and model provenance—commit hashes, parameter snapshots, and solver versions—made outputs auditable. Interoperability matured beyond file formats: IFC remained a backbone for exchange, but custom schemas and API-first services such as Rhino Compute and Speckle enabled more granular, testable flows. Firms began to articulate “DesignOps,” a practice of treating parametric workflows as systems that are built, tested, deployed, and monitored. This cultural shift reframed success metrics: not only beautiful results, but maintainable, versioned, and reproducible processes that can survive staff turnover, regulatory scrutiny, and project reruns.

- Python/C#/C++ extensions enable reusable, performance-aware components.

- COMPAS standardizes research-grade computation for real-world use.

- Git-based workflows bring review, testing, and provenance to design graphs.

- IFC, custom schemas, and APIs support robust, testable interoperability.

Conclusion: what algorithmic design changed—and what comes next

Shifts delivered

Algorithmic design recast architectural production from ad hoc form-making into reproducible, auditable, and optimizable workflows. With parametric graphs, a concept is no longer just a snapshot; it is a lineage of dependencies that anyone on the team can inspect, rerun, and extend. Analysis moved earlier: daylighting, energy, and structure now co-evolve with geometry, and their metrics steer options rather than veto them at the end. Fabrication tightened into the loop, binding tolerances and toolpaths to the same parameters that shape massing and detail. Equally significant is the social architecture: a community-driven innovation model of plugins, open-source projects, and conferences consistently outpaced traditional vendor roadmaps, turning users into co-authors of the platform they work on. As firms embraced source control and CI for definitions, models gained a paper trail that stands up to client and regulatory review. Perhaps the deepest shift is epistemic: design arguments now include datasets, fitness plots, and simulation traces alongside sketches and renderings, giving teams a richer vocabulary to defend choices and explore tradeoffs. In short, the field moved from product to process, from artifacts to systems, and from personal craft to collective, testable intelligence.

- Reproducibility and auditability became first-class outcomes.

- Analysis and cost/fabrication constraints informed early-stage exploration.

- Community ecosystems drove capability growth faster than closed roadmaps.

- Evidence-rich design narratives complemented intuition and precedent.

Ongoing challenges

Scaling the promise of algorithmic design exposes hard problems in governance, testing, and maintainability. Large Grasshopper or Dynamo graphs can become brittle without modularization, documentation, and version discipline. Inputs drift, plugin versions shift, and hidden assumptions pile up until reruns diverge. Interoperability remains uneven: while APIs and streaming help, long-term archiveability of parametric intent is fragile—IFC captures results better than the generating logic. Skill gaps persist, too. Computational literacy is not yet universal, and specialized teams risk creating dependence that undermines the democratizing spirit of visual programming. Organizations need patterns for code review, test data sets, and CI checks that run key solvers on known inputs, flagging regressions before they reach projects. Without these patterns, model trust decays. Finally, there is the human factor: sustainable adoption depends on training and incentives that align project schedules with the extra time needed to build robust pipelines. The field must normalize the idea that investing in design infrastructure—schemas, scripts, tests—is part of delivering value, not a side project, so that computational methods remain resilient across project cycles.

- Graph/code maintainability requires modularity and disciplined versioning.

- Parametric intent is difficult to archive and verify across tool lifecycles.

- Bridging skill gaps demands training without re-centralizing expertise.

- Testing and CI for definitions are vital to preserve trust and repeatability.

Near-future directions

The next horizon points toward cloud-native, headless computation for scalable optioneering and real-time feedback. Rhino Compute, Speckle Automations, and similar services make it routine to execute parametric graphs on servers, integrate them with dashboards, and expose them to collaborators through APIs. Expect deeper BIM-semantic integration as IFC evolves and semantic graphs clarify relationships beyond geometry, bringing codes, costs, and schedules into the same queryable fabric as shapes. Responsible AI will increasingly assist with scripting, optimization, and code review—LLM copilots that draft nodes, suggest graph refactors, and generate unit tests—augmented by verifiable simulation pipelines so that machine-generated suggestions remain grounded in physics and data. Hybrid modeling will mature, fluidly spanning solids, meshes, and voxels: solids for manufacturing interfaces and code compliance; meshes and voxels for analysis grids and volumetric logic; SubD for quickly shaping design intent that can later be rationalized. The organizations that thrive will treat parametrics as a platform: composable services, versioned schemas, telemetry on performance, and design knowledge captured as reusable libraries. In that world, the boundary between tool and practice dissolves; the “software” of architecture becomes the distributed protocol by which people, data, and machines continuously negotiate what a building should be.

- Headless execution scales exploration and brings live metrics into decision rooms.

- Semantic BIM and evolving IFC link geometry to codes, cost, and schedule.

- AI copilots assist authorship while verified solvers ensure correctness.

- Hybrid representations balance design freedom with fabrication fidelity.

Also in Design News

Revit Tip: Reference line rotation for stable, flexible Revit families

March 04, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …