Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

Design Software History: Industrial CAM and Hobbyist CNC: Divergent Lineages, Converging Practices

February 01, 2026 13 min read

Two lineages emerge: industrial CAM vs hobbyist CNC (1950s–2000s)

Industrial roots

From the first postwar numerical control experiments to the workstation era, the industrial lineage of computer-aided manufacturing coalesced around aerospace performance demands, heavy machine tools, and tightly coupled software-hardware stacks. In the 1950s and early 1960s, the U.S. Air Force sponsored a groundbreaking project at MIT’s Electronic Systems Laboratory led by Douglas T. Ross that yielded the Automatically Programmed Tool system, better known as APT. APT formalized cutter motion through a higher-level language of geometry and motion commands that compilers translated into axis moves, initially streamed to machines through punched paper tape. Standardization soon followed with the EIA/RS-274 specification, the ancestor to what became universally known as G-code. Early adopters such as Boeing and Lockheed used APT-based workflows to generate complex contoured surfaces for aircraft structures and turbine components that were impossible to describe with manual drafting alone. The practical reality of mid-century numerical control meant living with tape limits, logic relays, and expensive shopfloor electronics, but the seeds were planted: geometry in a computer describing motion in a machine.

As computing power diffused beyond mainframes, industrial CAM matured alongside CAD on minicomputers and later UNIX workstations and PCs. By the 1980s and 1990s, integrated CAD/CAM platforms unified model creation and toolpath generation into a single product development environment. Keys players included Unigraphics (later NX under UGS and then Siemens), CATIA from Dassault Systèmes, Pro/Manufacturing from Parametric Technology Corporation (PTC), and specialized CAM stalwarts such as Mastercam (CNC Software, founded by Mark Summers), GibbsCAM (Bill Gibbs’s Gibbs and Associates), DP Technology’s Esprit, and Delcam’s PowerMILL and FeatureCAM. Real-world production added another layer: controller dialects and post-processing. Fanuc, Siemens 840D, and Heidenhain each enforced distinct motion semantics and options, spawning commercial post ecosystems such as ICAM Technologies and IMS (Intelligent Manufacturing Software) to map neutral toolpaths to reliable machine code. Verification emerged as its own category with CGTech’s Vericut (founded by Bill Hasenjaeger and Bryan Laing) and later Spring Technologies’ NCSIMUL, enabling full machine-and-fixture simulation to avoid crashes. The industrial lineage thus grew around rigorous geometry, kinematics, and the discipline of validated posts and NC verification.

Hobbyist/maker genesis

While industry chiseled best practices in high-cost environments, a parallel lineage slowly formed around commodity PCs and community-driven control software. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the PC parallel port provided a lifeline: Art Fenerty’s Mach2 and later Mach3 (ArtSoft) leveraged software timing to drive step pulses directly from Windows machines, making computer control of benchtop mills and routers dramatically more affordable. In research circles, the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Enhanced Machine Controller (EMC) spun out as the open-source LinuxCNC, using real-time kernels to achieve stable motion on off-the-shelf hardware, a crucial step in democratizing closed-loop control concepts. A new wave followed: Arduino-class microcontrollers and inexpensive stepper drivers, with Simen Svale Skogsrud’s GRBL and Sungeun K. Jeon’s later enhancements placing basic RS-274 interpretation on an 8-bit board; Alden Hart’s Synthetos TinyG refined motion planning; and the Smoothieboard ecosystem broadened reach. This hardware base intersected with the maker movement’s ethos of shared designs and accessible kits: Shapeoko (Edward Ford) and OpenBuilds platforms lowered structural barriers while online communities lowered psychological ones.

On the software side, approachable 2.5D workflows took center stage. Vectric’s VCarve and Aspire (co-founded by Brian Moran and Tony McKenzie) brought intuitive V-carving and relief strategies to hobbyists, while Inventables Easel made browser-based CAM a reality. The idea of modeling and machining in one application reached hobbyists through Fusion 360 after Autodesk’s acquisition of HSMWorks, placing integrated CAD/CAM on home desktops. Crucially, education and distribution moved through forums and YouTube, where clear visual pedagogy and shared post-processor configurations accelerated confidence. The hobbyist lineage emphasized fast setup, community-verified recipes, and cost-conscious workflows over the industrial world’s deep verification and kinematics. Yet the DNA was recognizable: G-code remained the lingua franca, toolpaths described geometry into motion, and a growing cadre of makers internalized a professional truth—successful CNC outcomes live at the intersection of sound modeling, consistent control, and a well-understood machine envelope.

Divergent software stacks and toolpath technology

Industrial toolpath innovation

Industrial CAM’s defining advantage is its relentless toolpath innovation, tuned to the evolving physics of metal cutting and the mechanical bandwidth of modern machines. The progression from Z-level roughing and constant-scallop finishing toward high-speed machining (HSM) reflected a deeper understanding of chip thinning, cutter engagement, and jerk-limited motion. In the 2000s, “adaptive” or “trochoidal” strategies reshaped roughing: Autodesk’s HSM (originating in HSMWorks), Celeritive’s VoluMill, Mastercam’s Dynamic Milling, OPEN MIND’s hyperMILL HSC, and SolidCAM’s iMachining all sought to maintain constant tool load and maximize material removal without overloading the spindle or cutter. These algorithms emphasize smooth arcs, controlled stepovers, and engagement-aware feed control, partnering with controllers capable of look-ahead, spline interpolation, and dynamic path smoothing.

The shift mattered because it let shops push deeper axial engagement with smaller radial stepovers, unlocking speed and tool life simultaneously. In practice, advanced toolpaths are now rich with parameters that link the virtual model to cutting mechanics: optimal load, engagement angle limits, rest machining that senses remaining stock, and feed-rate scheduling keyed to curvature. Tool vendors—Sandvik Coromant, Kennametal, Seco, and high-performance end mill specialists like Harvey Tool and Helical—fed data-driven guidance back into CAM, aligning cutter geometries with algorithmic intent. For the industrial lineage, the software stack is essentially a physics-aware co-pilot, translating a designer’s shape into a set of cutter motions that respect both material science and the drive limits of the machine.

Multi-axis maturity and kinematics

Multi-axis capability marks another divide where industrial CAM matured into a full expression of geometry, kinematics, and process knowledge. Beyond 3+2 positioning, full 5-axis motion enabled strategies like swarf (flank) milling that uses the tool’s side to follow ruled surfaces, multi-blade routines for blisks and impellers, port machining inside contorted passages, and automatic collision-aware tool-axis tilting. Here, toolpath quality is inseparable from a machine’s kinematic model: post-processor and CAM kernel must understand rotary limits, singularities, and axis coupling to avoid impossible moves. Software such as NX CAM, CATIA CAM, hyperMILL, PowerMILL, and Esprit distilled this complexity into specialized strategies and templates, so programmers can select surface regions or feature categories and let the system solve feasible orientations.

Because 5-axis introduces new failure modes—gouges from unexpected tilts, reach limits, and abrupt rotary acceleration—industrial suites increasingly exploit spline-based interpolation and controller-native features (e.g., Siemens TRAORI, Heidenhain KinematicsOpt) to keep motions continuous. The practical impact reverberates in tooling and fixturing: slim holders, modular extensions, and strong collision models become mandatory, and probing cycles verify datum frames across compound setups. The payoff is geometric freedom and cycle-time efficiency that hobbyist controllers rarely attempt. Machine-aware toolpaths are now a hallmark of the industrial stack: they’re not just curves in space but plans that respect the distinct mechanical personality of a Mazak, DMG MORI, Makino, or Grob with its unique trunnion, fork, or gantry kinematics.

Verification, process planning, and posts

Industrial CAM’s safety net is a layered system of post-processing, verification, and process planning that narrows the gap between on-screen promises and what happens at the machine. A typical workflow sees a programmer generate a neutral toolpath, pass it through a tailored post-processor (ICAM, IMS, or native post tools) that emits controller-specific code, and then validate the exact NC output in machine simulation. Products like CGTech Vericut and Spring Technologies NCSIMUL build digital twins of the machine, fixture, and tooling to catch collisions, overtravels, and axis limit issues after post-processing. This distinction—verifying the posted NC, not just the internal toolpath—reflects decades of lessons about controller quirks and set-and-forget habits that can lead to catastrophic crashes.

Planning layers add sophistication: in-process stock models that propagate between operations; tool and holder databases synchronized with supplier catalogs; tool life and breakage models; and probing routines that update work offsets based on real measured surfaces. Shops often integrate DNC systems to manage program revisions and secure downloads, while machine monitoring standards like MTConnect stream spindle loads, alarms, and cycle times back to MES/PLM ecosystems. The result is a digital twin loop where posts, simulation, and shopfloor telemetry build trust. This ecosystem is heavier than anything in the hobby space, but it enables consistent, audited manufacturing where safety, cost, and throughput are inseparable concerns.

Deep CAD integration and model-based definition

At the high end, CAM is not a standalone tool but an extension of product definition. Suites like Siemens NX, Dassault Systèmes CATIA, and PTC Creo link CAM tightly with parametric CAD features, assembly context, and PMI/MBD (Product Manufacturing Information / Model-Based Definition). When a designer changes a fillet or updates a datum scheme, CAM operations can automatically rebuild associative curves, adjust boundaries, and preserve templates keyed to feature types. This reduces reprogramming time and maintains intent across revisions. Beyond geometry, PMI conveys tolerances, surface finishes, and datum structures directly to the CAM environment, enabling selection logic—finish passes for GD&T-critical surfaces, probing for tight datums, or alternative strategies for thin-wall regions.

Plug-in approaches brought similar benefits to mainstream mechanical CAD users. HSMWorks originated as a SolidWorks add-in before Autodesk expanded it into Fusion 360; CAMWorks and SolidCAM likewise live inside SolidWorks assemblies, while hyperMILL offers deep integrations with leading CAD platforms. Under the hood, robust B-rep and NURBS kernels maintain clean surface definitions for toolpath projection and offsetting. The philosophy is simple: minimize translation loss, keep design and manufacturing synchronized, and let the CAM programmer work where the geometry was born. This level of integration remains a hallmark of the industrial lineage and informs why high-end suites are selected as much for enterprise data management as for pure toolpath prowess.

Hobbyist controllers and UIs

The hobbyist lineage optimized for simplicity, cost, and approachability. Controllers like GRBL (and its GRBLHAL evolutions), TinyG, and Marlin forks interpret RS-274 subsets on microcontrollers, communicating with host PCs over USB serial rather than dedicated fieldbuses. Real-time determinism is handled either on the device or, in LinuxCNC/PathPilot’s case, by a real-time OS on the PC. User interfaces emphasize easy jogging, zeroing, and straightforward job streaming: Universal Gcode Sender, bCNC, Candle, ChiliPeppr, and OpenBuilds CONTROL became staple consoles, often complemented by community macros for probing and tool setting. Feature sets intentionally trim industrial complexity—limited macro systems, fewer canned cycles, and no rigid tapping unless paired with specific hardware—because the target machines are stepper-driven gantries or benchtop mills with basic spindles.

These constraints are a feature, not a bug, for first-time users. By limiting options and prioritizing clarity, hobbyist UIs reduce failure modes and cognitive load. Important concepts—work coordinate systems, homing, soft limits—are presented plainly, while post-processors avoid obscure controller codes. Makers quickly develop muscle memory around streaming, pausing, and resuming jobs and learn to guard against USB hiccups with reliable cables and conservative line buffers. Though simpler, the ecosystem has matured to cover most common workflows: quick fixture probing with touch plates, corner-finding macros, and camera-based alignment for PCBs or inlays. The contrast to industrial HMIs is stark, but the goal aligns: provide predictable, safe motion from a small, affordable machine.

Accessible CAM and practical limits

Hobbyist CAM emphasizes 2.5D contouring, pockets, and engraving, with approachable 3D surfacing for reliefs and simple molds. Vectric VCarve and Aspire led with intuitive toolpath dialogs and preview renders that reflect stepover and tool shape clearly, while Estlcam offered low-cost entry with practical defaults. Fusion 360 expanded the horizon by bundling parametric CAD, assemblies, and a CAM engine derived from HSMWorks, letting users draw a part and cut it without file shuttling. PCB-oriented tools like FlatCAM addressed a parallel niche. Yet the practical limits of the machines shape strategies: stepper-driven rigidity means conservative depths of cut; lack of through-spindle coolant and rigid tapping steer users toward thread milling or hand tapping; and simplified tool compensation encourages accurate measurement and careful zeroing rather than on-the-fly wear comp. In practice, hobbyists lean on vendor-supplied posts and proven wizards rather than full machine simulation and kinematic modeling.

Despite limits, accessible CAM has become remarkably capable. Makers routinely run adaptive roughing at conservative feeds on aluminum with trim routers and cut tidy hardwood joinery with V-bits and compression end mills. Clear visualization and instant simulation inside the CAM preview help avoid surprises, and community spreadsheets for chiploads and surface speeds provide a social knowledge base. The result is a pragmatic culture of “cut light, cut smart,” where repeatability and finish quality trump raw MRR. In this way, the hobbyist lineage’s software stack acts as a coach—encouraging safe toolpaths and emphasizing stock setup and fixturing—rather than a full-fledged process engineering environment.

Prosumer bridges

A noteworthy bridge between lineages is the rise of “prosumer” machines and controls that borrow industrial ideas while keeping total cost under control. Tormach’s PathPilot—built on LinuxCNC—brought conversational cycles, probing routines, and a polished UI to entry-level mills and lathes. That combination of open-source control with curated hardware created a platform where users can learn real-world concepts like G54 work offsets, tool length tables, and in-process inspection without facing a Fanuc manual on day one. Small-vendor ecosystems such as Carbide 3D introduced Carbide Create and Carbide Motion, bundling straightforward CAD/CAM and a stable sender with Shapeoko-class machines. Microfactory vendors increasingly ship verified post-processors and tool databases tuned to their spindles and common materials, shrinking the knowledge gap for new owners.

Meanwhile, components such as ATC retrofits, rigid frame kits, and probing accessories nudge hobby machines toward industrial capability. On the software side, adaptive roughing, rest machining, and 3D scallop finishing—once the province of high-end CAM—are now available in the hobby price tier. The impact is cultural as much as technical: users learn to expect machine-aware toolpaths, standardized tool libraries, and at least light-touch verification before committing stock. The prosumer bridge does not eliminate the gulf in kinematics or verification rigor, but it teaches a common vocabulary—feeds and speeds, engagement, probing, offsets—that makes later transitions to industrial environments smoother and safer.

Economics, licensing, and consolidation shaping both worlds (2010s–2020s)

Business models and M&A

The 2010s ushered in a consolidation wave that reconfigured the CAM landscape and blurred boundaries between hobbyist and industrial capabilities. Autodesk catalyzed change by acquiring HSMWorks in 2012 and Delcam in 2014, fusing high-performance toolpath kernels with cloud-centric product strategy and delivering capabilities such as adaptive clearing to a far broader audience through Fusion 360. Hexagon Manufacturing Intelligence built a CAM portfolio by absorbing Vero Software (Edgecam, Alphacam, Surfcam) and later acquiring DP Technology’s Esprit, centralizing diverse vertical expertise under a single analytics-savvy umbrella. Sandvik, the tooling giant, shifted from “steel and inserts” to software by acquiring CGTech (Vericut) in 2020, Mastercam/CNC Software in 2021, and Cambrio (housing GibbsCAM and Cimatron), aligning toolpath planning, simulation, and cutting tools within one industrial logic.

Licensing mirrored broader software trends. Industrial shops long relied on perpetual licenses with maintenance and dongles, often tied to ITAR/security controls and audited compliance. Over the decade, subscriptions gained ground, promising continuous updates, integrated cloud services, and lower upfront costs. In parallel, the hobbyist market normalized freemium and personal-use tiers (notably Fusion 360’s personal license), plus low-cost perpetuals like Vectric’s offerings that include major upgrades at user discretion. The net effect is feature diffusion: as companies aggregate toolpath IP and simulation technology, they cross-pollinate features downmarket while streamlining enterprise features upstream. More customers, at more price points, now expect HSM strategies, solid tool libraries, and reasonable post support out of the box.

Community and content networks

What textbooks once taught, community networks now accelerate. Tooling data pipelines such as MachiningCloud aggregated catalogs from Sandvik Coromant, Kennametal, Iscar, Seco, and niche brands like Harvey/Helical, piping real cutter geometries and parameters directly into CAM. Vendors embedded these feeds so programmers can pick a tool, pull verified geometry, and receive recommended chiploads and surface speeds. Education moved to forums and creator channels; figures like John Saunders of NYC CNC demystified feeds and speeds, fixture design, and probing with a transparency that textbooks seldom offered. Hardware vendors adapted: Carbide 3D (Rob Grzesek and Edward Ford), Bantam Tools, and others bundled curated posts, starter tool libraries, and training projects, reducing setup friction.

This content economy matters because it standardizes entry workflows across disparate machines. Consider the first-hour experience many new users now share: pick a material library, choose an end mill with a known profile, apply an adaptive roughing template with conservative defaults, simulate visually, and stream G-code with a known-good sender. The social proof of thousands of successfully replicated recipes reduces anxiety and shortens the path to first chips. In the industrial world, similar dynamics play out on professional forums and vendor academies, but filtered through quality and compliance lenses. Across both lineages, documentation is no longer just PDFs; it is living video, shared tool databases, and community-maintained posts that evolve with controller firmware and machine-specific quirks.

Interoperability and safety

Interoperability and safety highlight the remaining systemic differences. Industrial environments emphasize rigorous post/NC validation, closed-loop feedback, and data governance. MTConnect and OPC-UA frameworks shuttle telemetry from machines to dashboards, while PLM hooks tie CAM revisions to change orders and compliance records. Shops implement program approval workflows, restrict edit rights on the machine, and require NC simulation sign-offs with collision checks. Controller features like block-erase, single-block, and dry-run are used in concert with probing macros to validate setups before committing to metal. In this world, the cost of failure is measured in broken five-figure tools, damaged spindles, and missed delivery penalties, so software stacks are built to prevent surprises.

Hobbyist and prosumer setups trade institutional safeguards for simplicity. RS-274 subsets with minimal macros avoid execution ambiguity; posts are ad hoc but well-tested in the community; and verification often stops at CAM’s internal stock simulation. Instead of formal approvals, makers rely on “air cuts,” sacrificial stock, and conservative feeds. That does not mean the domain is unsafe—only that safety is achieved through culture and constraint rather than enterprise process. Encouragingly, cross-pollination is ongoing: lightweight machine monitoring, better homing/limit enforcement, and probing routines are seeping into open-source controllers, while industrial vendors simplify UIs and provide curated templates for small-business users. The convergence is pragmatic—bring essential safety forward without overwhelming users with enterprise overhead.

Conclusion

Convergence at the edges

The two lineages are unmistakably converging at their borders. Hobbyists now wield capabilities once reserved for enterprise: adaptive roughing that respects chip load, curated tool libraries from major vendors, probing macros that set work offsets with precision, and increasingly polished controllers that hide the rough edges of serial streaming. Industrial vendors, in turn, court small-to-medium businesses with approachable UIs, streamlined posts, and subscription tiers that reduce capital shock. The cultural feedback loop—forums, videos, cloud libraries—pulls expectations toward a middle ground where a first-time user can produce a respectable part in a weekend and a small shop can onboard a new programmer without a year-long apprenticeship. The remaining gap is less about toolpath math and more about systems: validation depth, data governance, and kinematic complexity that still belong to the high end.

Viewed historically, this is a recurring pattern. APT translated geometric intent into motion on room-sized computers; workstation-era CAD/CAM bound model and machine inside engineering departments; and now cloud platforms and open controllers spread the know-how across garages and microfactories. Each wave preserved the core insight—software is a multiplier on hardware capability—while broadening who can exploit it. The present convergence offers the benefits of both worlds: agility and community from the hobby side, and reliable, documented processes from industry. As vendors rationalize portfolios and communities codify best practices, the on-ramp to competent CNC narrows without erasing the richness of expert craft.

Persistent differences and the next wave

Even as features diffuse, fundamental distinctions will remain. Certified verification of posted NC code, 5-axis kinematics with singularity-aware motion planning, complex post chains, and governed processes tied to PLM are non-negotiable in regulated, high-stakes environments. No amount of UI simplification erases the need for traceability and the deep integration between design intent, inspection, and process planning that enterprise CAD/CAM suites deliver. Conversely, hobbyist and prosumer ecosystems will continue to prioritize cost, openness, and immediacy, favoring simpler controllers and simulation that provide “good enough” confidence at home-shop risk levels. Expect cross-pollination to continue: open-source controllers adopting richer cycles, kinematics, and probing; industrial vendors embracing cloud telemetry and AI-assisted feeds/speeds, path selection, and automated verification that will eventually trickle downstream.

The historical lesson is clear: breakthroughs follow platforms and communities. From APT’s academic consortium to workstation-era CAD/CAM to today’s cloud libraries and open controllers, progress accelerates when the knowledge to wield machines is codified and shared. The likely next leap will pair democratized control stacks—stable, real-time, and kinematics-aware—with robust, affordable machine-aware simulation that validates the exact NC before chips fly. When that arrives, the boundary between a garage and a production cell will feel far thinner. Users at every tier will benefit from a common foundation: geometric precision, trustworthy motion, and shared wisdom that keeps cutters in the work and crashes out of the newsfeed. In other words, the future of CAM remains what it has always been—software making machines smarter, safer, and more accessible, one line of code and one community at a time.

Also in Design News

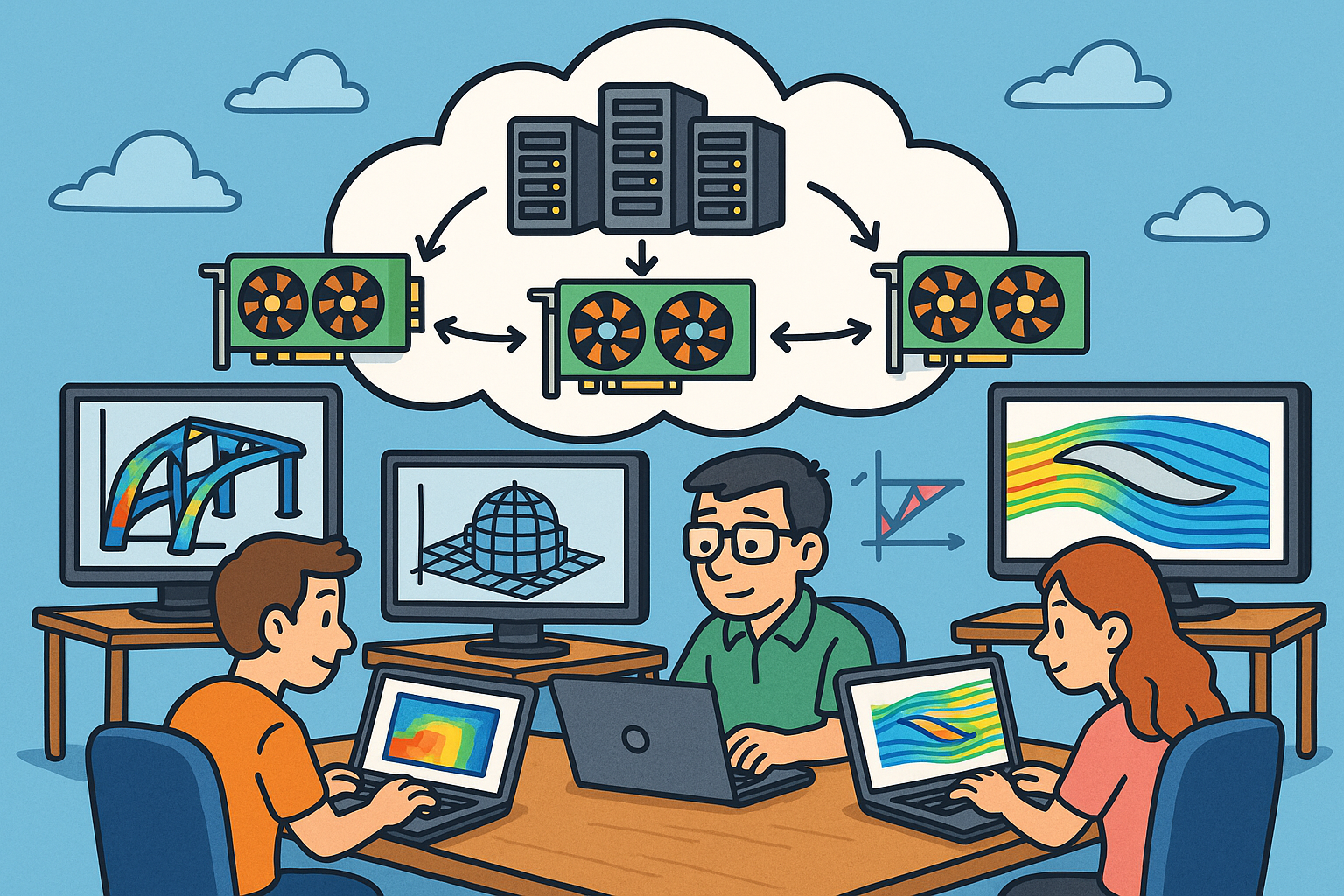

Cloud Multi‑GPU Architectures for Large‑Scale Multi‑Physics Design

February 01, 2026 11 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Optimize Cinema 4D Viewport Shading for Clarity and Speed

February 01, 2026 2 min read

Read More

V-Ray Tip: V-Ray Lens Effects: Subtle Bloom and Glare Workflow

February 01, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …