Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

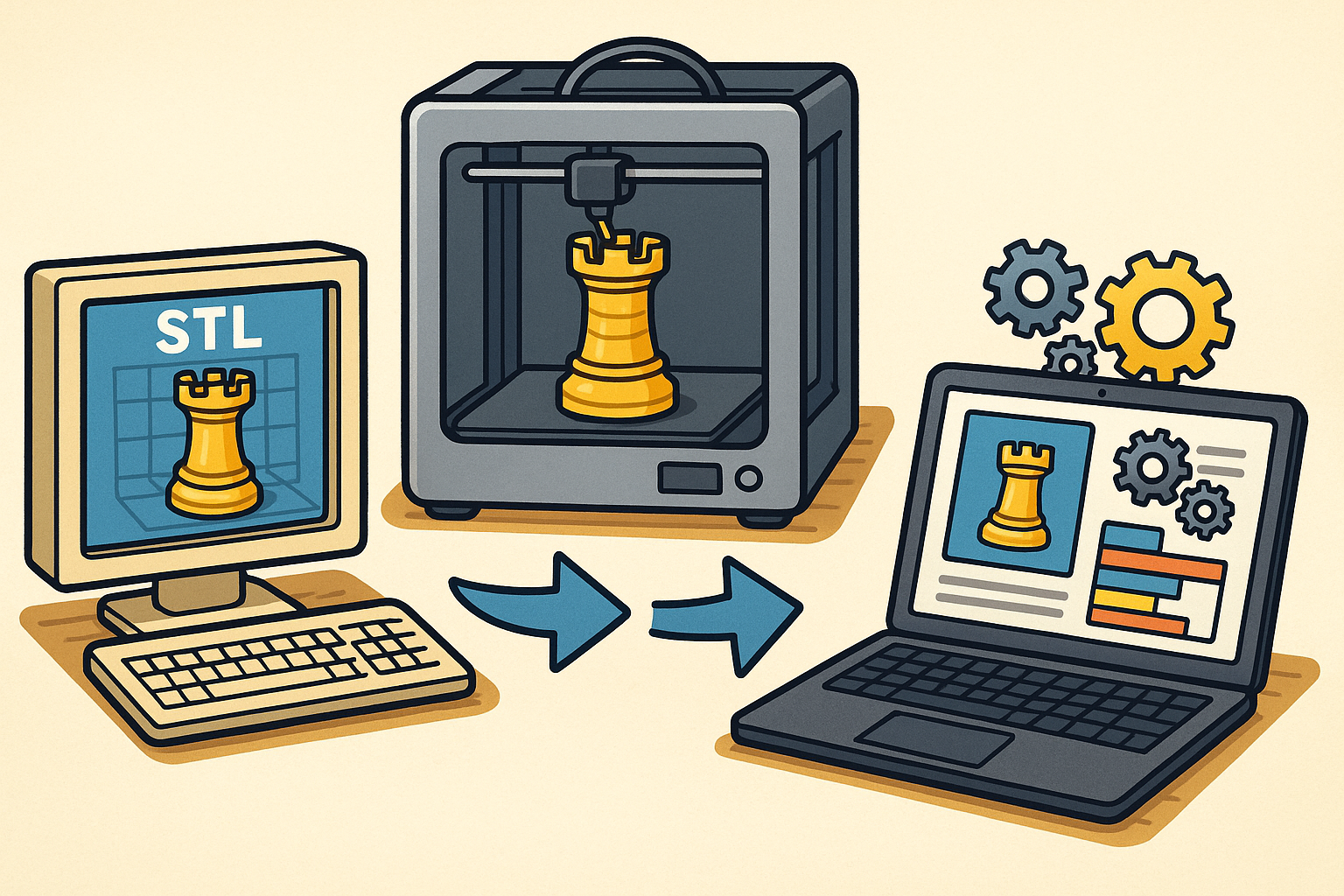

Design Software History: From STL to Manufacturing OS: The Evolution of Additive Manufacturing Software

December 21, 2025 14 min read

Origins: Rapid Prototyping Meets Software (1980s–2006)

Foundational moments

When stereolithography emerged from Chuck Hull’s lab at 3D Systems in 1986, it set in motion a feedback loop between machines, software, and the practices of designers and engineers that would define the first era of additive manufacturing. The first software epoch centered on the simple but revolutionary idea that you could transform a 3D digital model into thin layers, cure them with light or fuse them with energy, and obtain parts at speeds previously unthinkable for tooling-driven shops. The introduction of the STL format—a faceted representation of surface geometry—was at once the catalyst and constraint of this era. STL’s ubiquity meant anyone could export a print-ready model from a CAD system, yet its minimalism invited a decade of workarounds. While 3D Systems scaled SLA, S. Scott Crump at Stratasys pushed fused deposition modeling (FDM) into commercial reality, and EOS evolved powder-bed technologies including selective laser sintering (SLS) and later metal variants aligning with SLM/L-PBF concepts. What united these pioneers was not just novel mechanics, but the first generation of build-preparation pipelines—orientation heuristics, support rules, and slicing strategies—tied tightly to each vendor’s hardware and resin, filament, or powder recipes. In parallel, a service-bureau economy formed, where customers emailed STLs to bureaus that operated fleets of high-end machines, often in clean rooms and with specialized post-processing. Early adopters in automotive design studios, aerospace skunkworks, and medical research centers used these services to iterate faster on models and fixtures. The outcome was a canonical workflow: export, fix, orient, support, slice, and hope the open-loop build behaved.

- 1986: Chuck Hull and 3D Systems commercialize stereolithography and publish the STL interchange format.

- Stratasys introduces FDM, reframing thermoplastics as printable roads laid by numerically controlled nozzles.

- EOS advances SLS (and later metal powder-bed processes), anchoring a powder-centric software stack.

- Early ecosystems rely on service bureaus and proprietary machine-bound pre-processing pipelines.

Early software pillars

As adoption widened, software hardened into recognizable disciplines. Materialise, founded by Wilfried Vancraen in 1990, became the archetypal independent player with Magics, crystallizing the now-classic sequence of “fix, orient, support, slice.” Magics codified mesh repair—closing holes, resolving non-manifold edges, stitching shells, and remeshing—as a first-class competency, because STL’s bare triangles were unforgiving when translated into physical toolpaths. Orientation evolved beyond mere convenience into a science of balancing surface quality, support volume, and mechanical anisotropy. Automated support generation, first heuristic and later rule-driven with templates, transformed operator expertise into repeatable recipes. Slicers matured from linear scanline strategies to adaptive layer thickness and contour-infill decompositions that respected part features. These advances established “pre-processing” as a professional software category distinct from CAD. Yet the same period exposed STL’s limitations: no standard units, no color, no material assignments, no texture parameters, and only brittle associations between the mesh and its source CAD. Vendors tacked on proprietary comments and auxiliary files to pass printer-specific directives. Machine feedback remained sparse, so builds were open-loop, and failure analysis lived in spreadsheets and operator lore. Even in this environment, specialized pipelines took shape in medicine—the Materialise Mimics platform linked imaging data (DICOM) to anatomical segmentation and printable models, bridging radiology and surgical planning with clear patient-specific value.

- Materialise Magics defines industrial RP pre-processing: mesh repair, orientation, support creation, and slicing.

- Orientation moves from intuition to objective trade-offs among quality, support cost, and anisotropic strength.

- STL’s minimalism triggers vendor-specific metadata and ad hoc sidecar files to encode materials and parameters.

- Mimics connects medical imaging to printable models, enabling early surgical planning and device prototyping.

Industrial workflows

By the early 2000s, each machine OEM advanced its own end-to-end stack, hardwiring software to process physics. 3D Systems evolved SLA build tools and downstream platforms; Stratasys offered Insight and Catalyst to control road widths, raster angles, and support densities; EOS provided EOSRP and later EOSPRINT for powder-bed set-up; and proprietary protocols governed how slice data reached controllers. The result was a segmented market where software quality and capabilities could determine machine productivity as much as laser power or resin chemistry. Operators chose between vendor bundles and neutral tools like Magics or netfabb (pre-Autodesk acquisition), often combining them: fix in Magics, generate supports with templates, then hand off to a vendor slicer that knew how to dither exposures or plan recoating. Visibility back from the machine was meager: logs noted start and stop times and basic alarms, but melt pool behavior, resin vat health, or recoater interactions rarely fed upstream to inform decisions. The absence of tight feedback fostered over-engineered supports, conservative orientations, and manual post-build inspection regimes. Still, the workflows proved valuable enough to embed in enterprise processes—especially for jigs, fixtures, and low-volume polymer parts—while regulated domains like aerospace and orthopedics began to map traceability and documentation around them. In healthcare, Mimics-to-Magics-to-print pipelines connected hospital labs with service providers, often under bespoke quality systems. Across the board, the first AM era established the implicit contract that software must translate messy digital meshes into predictable physical layers, even when the printer spoke a proprietary dialect.

- Vendor-tied slicers (3D Systems, EOS, Stratasys) optimized for their physics and machine control semantics.

- Neutral pre-processing (Magics, early netfabb) fit between CAD and OEM tools, creating de facto middleware.

- Open-loop builds dominated; limited machine telemetry constrained adaptive strategies and qualification.

- Medical workflows integrated imaging (DICOM) to print via Mimics, with downstream preparation in Magics.

The Desktop FFF Explosion and Open-Source Toolchains (2007–2015)

Community-driven hardware and firmware

The RepRap project, initiated by Adrian Bowyer at the University of Bath, catalyzed a renaissance in distributed manufacturing and open engineering. RepRap’s idea—that a machine could print many of its own parts—translated into hardware kits, derivative designs like Darwin, Mendel, Huxley, and later the Prusa family, and a global ecosystem of tinkerers. Low-cost electronics (Arduino Mega + RAMPS), NEMA steppers, and commodity thermoplastics made experimentation accessible to students, makers, and startups. The software side mirrored this openness: Marlin, spearheaded by Erik van der Zalm and a wide contributor community, became the lingua franca of motion control for hobbyist FFF, while Repetier and Smoothieware provided alternatives with different planner and kinematic trade-offs. OctoPrint, created and stewarded by Gina Häußge, standardized the idea of a networked print server: a web UI, webcam monitoring, plugin-based extensibility, and remote G-code streaming to machines that were once tethered by USB cables. These projects baked community norms into firmware defaults—acceleration limits, jerk control, PID tuning—while exposing knobs for experimentation, from bed tramming to filament retraction. The cumulative effect was the democratization of toolchain development: bug fixes and new features shipped weekly, slicers talked directly to firmware quirks, and a shared troubleshooting vocabulary spread across forums and repositories. The open firmware wave also seeded future professional innovations by normalizing fleet monitoring, API-driven job start/stop, and sane defaults for motion planners that later influenced professional desktop machines.

- RepRap ignites a grass-roots hardware ecosystem with printable parts and shared designs.

- Firmware standards coalesce around Marlin, with Repetier and Smoothieware expanding options.

- OctoPrint mainstreams networked printing, webcam monitoring, and a plugin ecosystem.

- Open motion control and community norms accelerate iteration across hardware and software.

Slicing goes mainstream

Skeinforge, written by Enrique Perez, was the primordial soup for modern FFF slicing: a chain of modular scripts that converted STL meshes into extruder temperatures, head speeds, and XY toolpaths. While its interface and speed reflected its Python roots, it let power users dial every parameter of the deposition process. Slic3r, created by Alessandro Ranellucci, then made slicing accessible and fast, with pluggable infill patterns, configurable perimeters, and early support for multimaterial work. Cura, begun by David Braam and stewarded by Ultimaker, popularized real-time previews, a clean UX, and a pipeline that could scale from novices to power users through profiles and expert visibility toggles. Simplify3D emerged as a commercial alternative with granular process control and reliable supports, especially prized by early professional users. In this period, slicers matured core disciplines: automatic support structures that balanced removal ease and overhang stability; advanced infills—gyroid, cubic, honeycomb—that blended mechanical performance and print speed; modifiers and per-feature process settings that let users taper layer heights or vary wall counts by region; and multi-extrusion strategies for soluble supports and color. Visualizers improved trust by rendering accurate nozzle paths, showing bridges and overhangs in situ, and simulating print times with better kinematic models. The broader impact was two-fold: FFF became a credible prototyping tool in professional settings thanks to stable, well-understood slicers, and the open ecosystem cross-pollinated ideas at a rapid cadence, with fixes and features from one project quickly inspiring others.

- Skeinforge introduces modular slicing pipelines and exhaustive parameterization.

- Slic3r and Cura popularize fast slicing, profiles, and preview-driven trust in toolpaths.

- Simplify3D emphasizes per-process control, variable settings, and robust support management.

- Modern FFF features emerge: gyroid infill, tree supports, modifiers, and accurate time estimators.

Platforms, content networks, and format modernization attempts

The desktop boom thrived on network effects: models to print, services to fabricate, and formats to exchange richer intent. Thingiverse, developed under MakerBot (with notable early figures including Bre Pettis and Zach Smith), and YouMagine from Ultimaker built the culture of sharing parametric and mesh models, remixes, and print files. On-demand services like Shapeways, i.materialise, and Sculpteo exposed web APIs for quoting, automated repair, and materials selection, letting hobbyists and software startups embed “print” buttons in their products. These platforms anchored a feedback loop where design intent, manufacturability, and community benchmarking converged. At the same time, the industry faced the limitations of STL in a more acute way: even desktop users needed units, color, materials, textures, and assemblies with relative transforms. The AMF standard (ISO/ASTM 52915) answered with XML-based constructs for units, materials, and constellations, but its verbosity and limited tooling slowed adoption. In 2015, the 3MF Consortium—including Microsoft, Autodesk, HP, and Shapeways among others—proposed a compact, ZIP-based container with clear semantics for materials, textures, and references, and later, specialized extensions like the 3MF Beam Lattice for advanced microstructures. 3MF’s design acknowledged the practical need for portability and extensibility, enabling both desktop and industrial pipelines to exchange more than triangles. While STL remained entrenched for simplicity and legacy reasons, 3MF set the trajectory toward data-rich handoffs, a prerequisite for trustworthy, automated pre-processing at scale.

- Community content hubs (Thingiverse, YouMagine) normalize shareable, remixable models.

- Service APIs (Shapeways, i.materialise, Sculpteo) automate quoting, repair, and material selection.

- AMF brings units and materials but struggles with adoption due to complexity and ecosystem inertia.

- 3MF establishes a compact, extensible container with textures, materials, and beam-lattice semantics.

Vertical Integration and Industrial AM Software Stacks (2014–Present)

Vendor suites and consolidation

As additive leapt from prototyping to production, software reoriented around integrated suites that spanned design, simulation, build prep, machine control, and operations. Autodesk’s 2015 acquisition of netfabb pulled a beloved mesh and build-prep tool into a broader Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) vision alongside Within (implicit lattice/topology technology) and Autodesk’s simulation assets, ultimately bridging into Fusion 360 and specialized Netfabb editions. Stratasys consolidated workflows into GrabCAD Print, abstracting away traditional slicer complexity with printer-aware profiles while retaining Insight for advanced control. 3D Systems launched 3D Sprint and later acquired Oqton in 2021, aligning build preparation with AM MES, AI-driven scheduling, and traceable production analytics. HP’s Multi Jet Fusion arrived with SmartStream, an end-to-end preparation and packing environment designed for polymer part factories. EOS built EOSPRINT for L-PBF set-up and EOSTATE for monitoring and quality dashboards, while Renishaw’s QuantAM targeted metal build preparation. In the desktop-to-pro SLA/DLP segment, Formlabs’ PreForm exemplified a frictionless, printer-tuned pathway from mesh to part, making advanced supports and orientation accessible without expert tweaking. GE Additive integrated build-prep and simulation across Concept Laser and Arcam portfolios, recognizing that distortion compensation and parameter mapping were inseparable from MRO and certification flows. Through all of this, Materialise kept the mantle of neutral middleware: Magics and Build Processor bridged heterogeneous fleets, and Streamics evolved into CO‑AM, a cloud platform for factory orchestration that speaks to machines from multiple OEMs.

- Autodesk integrates netfabb, Within, and simulation into cohesive DfAM toolchains.

- Stratasys focuses on GrabCAD Print for ease-of-use and Insight for advanced control.

- 3D Systems pairs 3D Sprint with Oqton for MES, compliance, and analytics across fleets.

- HP SmartStream, EOSPRINT/EOSTATE, Renishaw QuantAM, and Formlabs PreForm align software to process physics.

- Materialise remains a multi-OEM bridge: Magics, Build Processor, Streamics/CO‑AM.

Design-to-manufacture intelligence

With production the goal, software began “reasoning” about materials and machines at design time. Generative and topology optimization matured from academic demonstrations to practical, solver-driven workflows. nTopology, founded by Brad Rothenberg, championed field-driven design with implicit modeling and robust lattice/TPMS operators that scaled to industrial resolutions. Altair’s Inspire Print3D added additive-aware topology optimization and support prediction, while Ansys and Siemens’s Simcenter Additive built direct paths from simulation to compensated geometry. PTC brought generative design to Creo by acquiring Frustum, aligning lightweighting with production constraints. Carbon’s Design Engine, complemented by the acquisition of ParaMatters, emphasized the co-design of part geometry and process parameters for its DLS resin platform. These tools converged on a few big ideas: implicit/volumetric representations that sidestep mesh fragility; lattice and TPMS structures that tune stiffness, weight, and permeability; and parameterization that treats orientation, supportability, and surface criticality as first-class design inputs. The 3MF Beam Lattice extension provided a compact way to exchange complex periodic and stochastic structures without exploding file sizes, enabling cross-tool handoffs while preserving feature intent. Meanwhile, automation crept deeper into build prep: Materialise e-Stage drove automated SLA support design; heat-map orientation evaluated trade-offs across surface finish, support, and build time; and advanced packing/nesting for SLS/MJF turned constrained build volumes into yield-optimized arrays that respected thermal and recoating considerations. The result is a feedback-rich loop in which parts are “born additive,” and software encodes manufacturability before the first slice exists.

- Implicit modeling and field-based lattices scale complex geometry without brittle meshes.

- Generative/topology tools (nTopology, Altair, Ansys/Simcenter, PTC/Frustum, Carbon) integrate process-aware constraints.

- 3MF Beam Lattice enables portable, compact lattice exchange across the toolchain.

- Automated supports, heat-map orientation, and packing/nesting enhance repeatability and throughput.

Process simulation, monitoring, and qualification

Production-grade additive demanded a new level of predictive fidelity and documented control. Metal L-PBF, EBM, and even high-power polymer processes introduced distortion, residual stress, and microstructural phenomena that couldn’t be hand-waved away with thicker supports. Ansys Additive, Simufact Additive (under Hexagon), and Abaqus-based workflows modeled heat input, scan strategies, and layer-wise accumulation to predict warping, cracking, and recoater collisions. The addition of pre-deformation (geometry compensation) closed the loop from simulation back to CAD/mesh. Additive Works’ Amphyon, later integrated into Hexagon’s offerings, refined parameter optimization and support strategies under simulated physics. In parallel, in-situ quality assurance emerged: layer imaging, photodiode and camera-based melt pool analytics, and tomographic approaches streamed gigabytes of data. EOS’s EOSTATE MeltPool, Renishaw’s in-situ monitoring packages, and Sigma Labs’ PrintRite3D pushed analytics into production dashboards. Yet, translating signals into actionable control remained hard; many systems still stop short of closed-loop control, focusing instead on part qualification, anomaly detection, and lot-level traceability. Regulated industries pushed software deeper into PLM/PDM. Siemens NX AM integrated with Teamcenter to embed process definitions, machine parameters, and consumable lots into formal configurations. Dassault Systèmes wrapped additive workflows into 3DEXPERIENCE, aligning model-based systems engineering with materials and process plans. The net effect is that qualification—once a binder of tribal knowledge—now lives as digital artifacts: build records, parameter sets, per-layer images, and approvals that trace a part’s journey from design to certificate.

- Physics-based simulation predicts distortion and residual stress, enabling geometry compensation.

- In-situ monitoring (layer imaging, melt-pool analytics) feeds dashboards for QA and anomaly detection.

- Regulated workflows enforce traceability via PLM/PDM integration (NX AM/Teamcenter, 3DEXPERIENCE).

- Closed-loop ambitions grow, but many systems remain analytics-first rather than adaptive-control-first.

Production operations and ecosystems

Beyond the toolpath, factories needed orchestration: quoting, scheduling, serialization, and compliance at fleet scale. Authentise, 3YOURMIND, Oqton, and Link3D (later acquired by Materialise) built AM MES layers that linked RFQs to routings, traveler documents to machines, and post-processing steps to quality gates. Their systems ingested CAD/STL/3MF, ran DfM checks, and selected build strategies based on material, geometry, and capacity constraints, while emitting the artifacts needed for audits. Cloud print networks matured: 3D Hubs—now Hubs under Protolabs—evolved from peer-to-peer FFF hubs to a curated network spanning CNC and injection molding, while Shapeways refined its own digital factory stack for polymers and metals. Security and provenance entered the mainstream as IP-sensitive parts moved through distributed supply chains. Watermarking and serialization tied digital models to physical builds, machine-to-cloud telemetry preserved process states, and policy engines gated who could slice, export, or print certain models and parameter sets. This era also emphasized APIs: from quoting to build release, systems needed to talk to PLM, ERP, QMS, and data lakes, standardizing identifiers and schemas so that a “job” meant the same thing across design, simulation, machines, and inspection. In effect, the old notion of a printer driver blossomed into a full-stack manufacturing OS layered atop heterogeneous fleets, where build slots, powder lots, and operator certifications are as programmatic as toolpaths.

- AM MES platforms (Authentise, 3YOURMIND, Oqton, Link3D) unify quoting, routing, and compliance.

- Cloud networks (Hubs/Protolabs, Shapeways) connect CAD, pricing, DfM, and fulfillment under SLAs.

- Security/provenance mature via watermarking, serialized logs, and machine-to-cloud telemetry.

- APIs and data schemas align MES/PLM/ERP/QMS into an operational backbone for additive factories.

Conclusion

What changed

The journey from stereolithography’s first cured layers to today’s qualified production lines reshaped software from a glue layer around STL files into a multi-layered, data-rich platform. Early workflows obsessed over making meshes printable—repairing triangles and coaxing slicers into consistent results. Now, the leading stacks weave design, simulation, and operations into a single continuum where parts are designed with their thermal histories and certification plans in mind. The open-source wave democratized access, slashing the cost of experimentation and normalizing concepts like remote printing, profiles, and plugin ecosystems. In parallel, industrial suites prioritized repeatability, auditability, and throughput, baking in factory constraints from the outset. Formats evolved accordingly: STL remains a lingua franca for quick exchange and legacy compatibility, but the center of gravity is moving to 3MF, whose extensible schemas handle the realities of materials, textures, assemblies, and lattice-rich designs. Most importantly, the AM software stack learned to speak upstream and downstream—with CAD kernels, solvers, machine controllers, and MES/PLM—so that every change in orientation, support strategy, or parameter set ripples through simulations, inventory, and quality records. In short, the field grew up: from fixing files to engineering processes; from single-build gambles to statistical control; from print farms to manufacturing OS layers that understand people, machines, and materials as data.

- Software expanded from mesh repair and slicing to integrated design-simulation-operations platforms.

- Open-source communities broadened access; industrial suites reinforced compliance and scalability.

- 3MF and beam-lattice semantics enable richer, portable design intent across tools and vendors.

- End-to-end data continuity replaces ad hoc handoffs and manual record-keeping.

Persistent tensions

Even as the stack matures, fault lines persist. STL’s inertia is real: its simplicity, ubiquity in CAM/CAD exports, and compatibility with lightweight viewers keep it in circulation—even when it undermines materials and color fidelity. Proprietary kernels, closed machine APIs, and vendor-bound process parameter sets collide with the desire for open ecosystems and multi-OEM shops seeking leverage and resilience. Desktop experimentation, with its ethos of “print, tweak, repeat,” often clashes with validated industrial chains where any change to orientation or support density may require requalification and documentation. Machine data standards remain fragmented; telemetry formats, register maps, and control hooks vary so widely that true closed-loop builds—where in-situ signals drive layer-by-layer compensation—remain the exception. Meanwhile, the cost of computational fidelity is a double-edged sword: high-resolution simulations and implicit modeling pipelines demand GPU-heavy infrastructure and workflow discipline. Finally, the human element endures: training, tribal knowledge, and local “tricks” influence outcomes as much as software versions or firmware updates, and codifying that know-how into templates and policies is an ongoing challenge for both OEMs and MES vendors. The mature future will need to accommodate these tensions, not erase them: enabling openness without sacrificing validation, and unifying data flows while respecting machine-specific physics.

- STL vs. 3MF: convenience and legacy compatibility versus data-rich, standardized exchanges.

- Open toolchains versus proprietary machine APIs and parameter ecosystems.

- Desktop agility versus industrial validation and requalification burdens.

- Fragmented telemetry and control standards slow progress toward adaptive, closed-loop processes.

Where it’s heading

The next phase points toward convergence on volumetric design and toolpath-aware planning. Implicit and field-based representations will become first-class citizens in CAD, not just in niche DfAM tools, allowing designers to encode spatially varying properties—stiffness, porosity, damping—directly. Beam-lattice standards in 3MF will broaden to include graded metamaterials and manufacturing constraints that account for minimum feature sizes and scanning strategies. Toolpath awareness will rise upstream: topology optimization and generative engines will consider hatch spacing, contour passes, and thermal histories during shape synthesis, reducing the gulf between “pretty” forms and printable, compliant geometries. On the shop floor, closed-loop builds will inch closer to reality as monitoring signals feed adaptive exposure, path resequencing, and next-layer compensation. That requires machine vendors to standardize telemetry and control hooks, and software vendors to deliver robust, real-time decision engines. Operations will tighten as MES/PLM/ERP converge: serialized powders and resins tracked like aerospace fasteners, automated traceability baked into digital travelers, and AI-assisted planning, inspection, and root-cause analysis providing guidance instead of just dashboards. Ultimately, the “printer driver” metaphor gives way to a full-stack manufacturing OS that spans design intent, physics-informed toolpaths, monitored execution, and evidence-backed certification. In that world, design software will start every project by reasoning about machines, materials, and approval pathways from the first sketch—because in production additive, software is the process.

- Volumetric/implicit modeling and beam-lattice standards become mainstream in CAD and exchange.

- Toolpath-aware generative design shortens the gap between concept and qualified build.

- Real-time monitoring informs adaptive exposure and compensation for more stable closed-loop control.

- Deeper MES/PLM/ERP integration automates traceability, with AI assisting planning and inspection.

Also in Design News

Heat-Treatment and HIP Simulation in CAD/PLM: Turning Post-Processing into a Design Variable

December 21, 2025 12 min read

Read More

Cinema 4D Tip: Cinema 4D: Export Multi‑Layer OpenEXR for AOV‑Driven ACES/OCIO Compositing

December 21, 2025 2 min read

Read More

V-Ray Tip: VFB Color Corrections Pass for Non-Destructive, Consistent Grading

December 21, 2025 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …