Your Cart is Empty

Customer Testimonials

-

"Great customer service. The folks at Novedge were super helpful in navigating a somewhat complicated order including software upgrades and serial numbers in various stages of inactivity. They were friendly and helpful throughout the process.."

Ruben Ruckmark

"Quick & very helpful. We have been using Novedge for years and are very happy with their quick service when we need to make a purchase and excellent support resolving any issues."

Will Woodson

"Scott is the best. He reminds me about subscriptions dates, guides me in the correct direction for updates. He always responds promptly to me. He is literally the reason I continue to work with Novedge and will do so in the future."

Edward Mchugh

"Calvin Lok is “the man”. After my purchase of Sketchup 2021, he called me and provided step-by-step instructions to ease me through difficulties I was having with the setup of my new software."

Mike Borzage

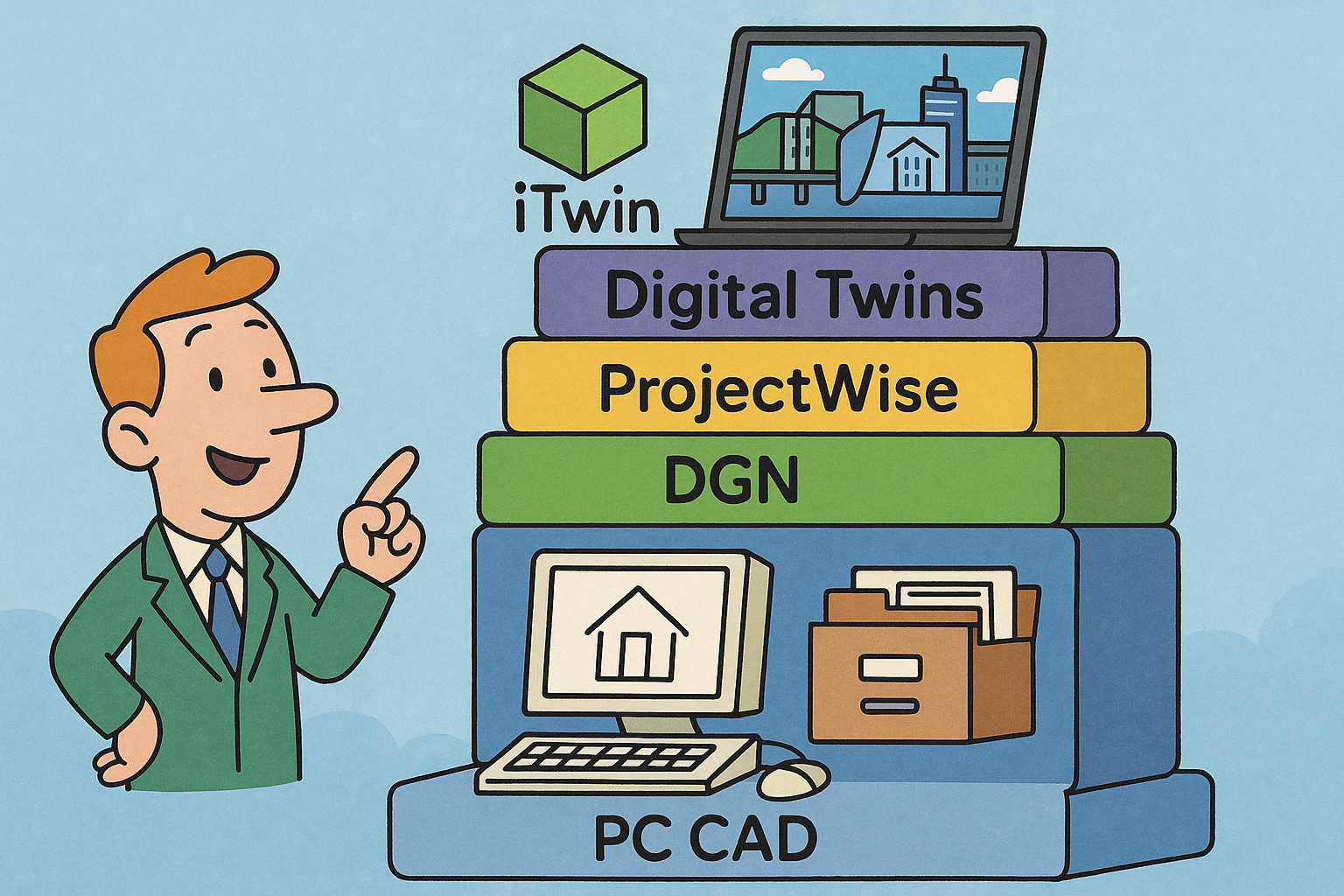

Design Software History: Bentley Systems: From PC CAD to an Infrastructure Stack — DGN, ProjectWise, iTwin and Digital Twins

January 10, 2026 14 min read

Infrastructure software has always moved to a different drumbeat than general-purpose CAD. Instead of short product cycles and disposable drawings, roads, rail, water, and power require a memory that spans decades, sometimes a century. That’s the lens through which the arc of Bentley Systems makes the most sense: a steady evolution from PC-born CAD insurgents to infrastructure specialists who fused modeling, analysis, and operations. What follows traces how the company’s people, products, and platform choices cohered around data longevity, owner-operator pragmatism, and a belief in open, federated information models. By connecting early 2D/3D drafting, linear-referenced civil geometry, analysis engines for structures and hydraulics, and—more recently—reality modeling and digital twins, Bentley built an “infrastructure stack” tuned to scale, fidelity, and change provenance. The pattern is consistent: find the long-lived information containers, keep them stable, make them interoperate, and grow depth through acquisitions that knit modeling to simulation and construction. The story moves through the founding era and Intergraph partnerships, the 1990s–2000s consolidation of civil and structural portfolios, the 2010s–2020s tilt toward cloud, photogrammetry, and the iTwin Platform, and finally the present lessons and signals for what’s next—AI-infused civil modeling, resilience analytics, and platforms where owners, engineers, and constructors co-author the infrastructure graph.

Origins and positioning: from PC insurgents to infrastructure specialists (1980s–1990s)

Founding and people

Bentley Systems began in 1984 as a family startup with a distinctive split of roles and personalities: Keith Bentley drove platform architecture and would become long-time CTO; Greg Bentley ultimately took the helm as the public face and long-serving CEO; Barry and Ray Bentley rounded out a team that combined engineering rigor with entrepreneurial pragmatism. The brothers were not outsiders to the minicomputer/engineering world—they understood the power of Intergraph’s IGDS ecosystem yet sensed the PC’s inevitability. Their early efforts were aimed at making high-end drafting and design workflows affordable and accessible on commodity hardware without sacrificing reliability or geometric precision. That combination—PC economics with enterprise-grade engineering—set a tone that persisted for decades.

In the mid-1980s, the industry still revolved around workstations and proprietary environments. The Bentleys saw that democratization would not mean dumbing down; it meant pushing more intelligence into files and models while pruning infrastructure costs. The company’s founding narrative also reflects a culture that prized long-term stewardship—Keith’s reputation for deep, low-level engineering and Greg’s focus on alliances and business durability coexisted productively. As they courted early customers, especially infrastructure owners and public authorities, the brothers learned that adoption hinged on trust: stability of file formats, predictable upgrade paths, and transparency of data models mattered as much as rendering speed. By the end of the decade, that ethos had congealed into a strategy that kept Bentley’s center of gravity in infrastructure, even as others chased broader design markets.

Early product thesis

The earliest expression of the thesis came with PseudoStation, a clever bridge that brought Intergraph’s IGDS workflows to the PC, and then with MicroStation, which emerged as a robust, interoperable CAD environment built for engineering accuracy. The technical logic was straightforward: preserve the geometry, symbology, and referencing habits of IGDS users, but deliver them on Windows and DOS-era PCs with efficient graphics pipelines and file I/O. MicroStation’s reference file system—its ability to federate multiple drawings and models—encouraged the multi-discipline coordination that civil and structural projects require. Over time, MicroStation’s geometry stack added B-splines, solids based on widely used kernels, and precision controls necessary for surveying, alignments, and detailing. The essential bet was that a strong, stable container would outlast any one machine architecture.

That container was the DGN file format. From the outset, DGN was treated not merely as a drawing file but as an enduring vessel for infrastructure semantics: coordinate systems, level structures, symbology rules, and references that survive team churn and toolchain diversity. MicroStation’s interoperability with DWG—especially through rigorous translators and later direct handling—acknowledged mixed environments. But Bentley’s differentiation lay in DGN’s staying power: explicit commitments to forward compatibility, long-lived element IDs, and a discipline against breaking schemas lightly. This meant that civil and utility owners could expect a design’s core geometry to remain usable across software generations. The thesis scaled elegantly with external references, cell libraries, and eventually 3D solids, creating a “federated model” habit long before cloud CDEs made the term fashionable.

Market fit and users

Infrastructure owners—departments of transportation, railways, utilities, and universities—gravitated toward Bentley because the company understood the life cycles and liabilities of long-lived assets. These organizations needed drawings and models that would still be intelligible in 10, 20, or 50 years. They also needed the software vendor to respect local standards, linear referencing conventions, and survey control. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the partnership era with Intergraph shaped Bentley’s emphasis on large projects and owner-operator use cases, including submittal workflows, plan production, and the management of linear assets where alignment geometry is the backbone.

Several characteristics made the fit compelling:

- A federated referencing model that allowed large corridors, stations, and utility networks to be decomposed into manageable design files without losing context.

- Strong precision geometry for alignments, parcels, and profiles, crucial for DOT drawings and right-of-way documentation.

- Interoperability with DWG and, critically, a stable DGN that could be archived confidently.

- Early attention to large-format plotting, raster underlays, and public-plan deliverables.

Building the infrastructure stack: vertical depth through products and acquisitions (1990s–2000s)

Collaboration and data management

By the mid-to-late 1990s, the scale and dispersion of infrastructure projects forced a reckoning: networked teams required something beyond shared drives and ZIP files. Bentley’s answer, ProjectWise, established a common data environment (CDE) before that term was codified in standards. ProjectWise introduced managed work-in-progress, document control, check-in/check-out, and, crucially, reference-aware relationships so that the federated MicroStation model could travel intact across organizations. Over time, Bentley added distributed caching, delta file transfers, and workflow states tied to transmittals and reviews. In effect, ProjectWise reified the best practices of multi-discipline collaboration that had grown up around MicroStation into a server-backed system that respected enterprise IT constraints and security.

At the turn of the 2000s, Bentley delivered DGN V8, an architectural watershed that promised long-term stability. V8’s expanded element schemas, enhanced level management, and improved Unicode handling signaled that the format would remain a reliable archive for decades. Just as important, Bentley sharpened DWG interoperability to reflect the “mixed-toolchain reality” on most projects. This meant designers could move data between MicroStation and AutoCAD ecosystems with minimal loss, keeping owners out of vendor lock-in. The combination of ProjectWise and V8 created a durable backbone: a managed environment that aligned with enterprise workflows and a format that resisted disruption. As databases like SQL Server and Oracle became staples of enterprise IT, ProjectWise also evolved integrations for metadata, search, and audit trails, moving beyond simple file servers toward a governed information layer for infrastructure projects.

Civil design consolidation

In the 1990s and 2000s, Bentley consolidated a fragmented civil landscape into a coherent toolkit. InRoads and GEOPAK—dominant road and land development applications with deep roots in survey, geometry, and corridor modeling—became the pillars of Bentley’s civil portfolio. Each product family brought loyal user communities and regional strengths, but their technical ambitions converged: parametric alignments, dynamic cross-sections, superelevation rules, earthwork volumes, and corridor templates managed as reusable libraries. Over time, Bentley invested to harmonize these capabilities and eventually set course toward a unified platform that would later surface under the “Open” brand. The aim was clear: model once, derive many deliverables, and embed design rules that scale across teams and standards.

Bridges and structures rounded out the civil continuum. Bentley added LEAP Bridge for concrete design and analysis, RAM for building structures, and STAAD.Pro through the acquisition of Research Engineers International, broadening into steel and global analysis workflows. The intent was to close loops: alignments feed bridge and retaining structure models, which then feed into load paths, rebar detailing, and fabrication deliverables. By connecting corridor modeling with structural analysis tools, Bentley enabled engineers to coordinate geometric intent and analytical reality. The stack embraced the principle that civil design is not just about drawings; it’s about propagating design intent from survey through analysis to construction documents, reducing translation loss and rework. That principle later informed the model-based deliverables strategy across the portfolio.

Water and utilities modeling

With the acquisition of Haestad Methods, Bentley brought water distribution, wastewater, and stormwater simulation into the fold via WaterCAD, WaterGEMS, SewerCAD, and HAMMER. This move recognized that municipal infrastructure depends as much on hydraulics and transients as on corridor geometry. Thought leaders like Tom Walski helped articulate methodologies that entwined operations and planning: scenario management, demand allocation, fire flow analysis, and pressure zone optimization became first-class citizens in the engineering process. The products embraced standards and practices such as EPANET compatibility, calibration tools, and GIS-driven network assembly so that asset inventories could be modeled and validated efficiently.

Bringing these applications into the Bentley stack enabled a powerful pattern:

- Leverage GIS and as-built data to rapidly assemble network models with consistent topology and attributes.

- Run steady-state and extended-period simulations to stress-test the network under growth and outage scenarios.

- Use surge analysis (HAMMER) to mitigate transient risks at pump starts/stops and valve operations.

- Close the loop with capital planning by comparing scenarios and costs against level-of-service goals.

Offshore, geotechnical, and GIS integration

Beyond civil corridors and water networks, Bentley moved into offshore and subsurface domains where failure modes are unforgiving and the physics are nontrivial. SACS provided offshore structural analysis capabilities for fixed platforms, jackets, and floating systems, addressing fatigue, environmental loading, and code compliance that go well beyond typical building design. This broadened the portfolio’s analytical depth and brought oil and gas infrastructure into the conversation. On land, the geotechnical front advanced through integrations that would later culminate in stronger offerings, but even in the 2000s Bentley recognized that soils are not a footnote; they are the medium in which infrastructure lives.

Geospatial integration matured with early Bentley Map and related extensions aimed at linear-referenced asset owners. Railroads, DOTs, and utilities needed to connect CAD precision to GIS context: stationing, mileposts, dynamic segmentation, coordinate systems, and event tables had to align. The software made it possible to treat location as more than a drawing attribute—it became a first-class index for assets, inspections, and work orders. Key practices took hold:

- Use of authoritative coordinate systems and transformations so survey-grade geometry retains integrity in GIS views.

- Linear referencing that preserves alignment stationing across design, construction, and maintenance phases.

- Attachment of attributes and relationships that can be surfaced in both CAD and GIS without duplication.

From CAD files to digital twins: reality, construction, and cloud platforms (2010s–2020s)

Reality and construction integration

The 2010s brought a wave of technologies that collapsed the gap between the modeled and the real. Acute3D’s photogrammetry engine, commercialized by Bentley as ContextCapture, made it feasible to generate large-scale reality meshes from ordinary photographs—drones, smartphones, and aerial flights—at unprecedented fidelity. Paired with Pointools’ point-cloud processing and LumenRT’s real-time visualization, engineers could situate designed assets inside photorealistic context and iterate with stakeholders who finally saw what “to scale” means. The technologic throughline was simple: reality capture is not a vanity add-on; it’s a reference surface for design, clash, and construction verification.

On the construction front, Bentley’s acquisition of SYNCHRO brought 4D planning—time-sequenced construction simulation—into the mainstream of infrastructure delivery. Embedding schedule logic in the 3D model aligns trades, mitigates spatial/temporal clashes, and helps constructors forecast laydown areas, crane picks, and access routes. InspectTech extended the flow downstream by supporting inspections for bridges and other assets, letting condition data feed maintenance decisions within governed workflows. Together, these capabilities created a practical loop:

- Capture existing conditions into point clouds and meshes to anchor design truth.

- Model and analyze with geometry that is context-aware and traceable.

- Plan construction in 4D to de-risk logistics and safety.

- Inspect and monitor assets so that operations data informs future projects.

iTwin era and platform strategy

What began as iModels and iModelHub evolved into the iTwin Platform, with iTwin.js as its open-source front door, and change-tracking at its core. The shift reframed design artifacts as time-series information: each change is an event with provenance, authorship, and impact. Deployed largely on Microsoft Azure, iTwin services expose APIs for ingestion, synchronization, visualization, analytics, and validation, allowing partners and owners to build their own applications atop Bentley’s infrastructure graph. The technical pattern emphasizes federation over monoliths: existing CAD/BIM files and analytical models are synchronized into an indexed, queryable twin without flattening them into a single schema.

Parallel to the platform, Bentley advanced its “Open” applications—OpenRoads, OpenRail, OpenSite, OpenBridge, OpenBuildings, and OpenUtilities—so that rules-based modeling and schema-rich data could flow naturally into iTwin. These applications share geometric engines, civil rules for corridors and turnouts, structural analysis integrations, and deliverables strategies that emphasize model-based sheets and reports with provenance. Key advantages emerged:

- Change intelligence: who changed what, when, and why, with automatic diffs across disciplines.

- Analytics: from quantity takeoff confidence to clash and code checks that can be automated.

- Openness: the ability to interoperate with DWG, IFC, and other ecosystems without data loss.

Strategic alliances and scale

Scale and credibility often hinge on alliances that marry domains. The Siemens-Bentley alliance created PlantSight to link design information with industrial operations data, bringing process engineering and asset performance management closer together. Partnerships with Topcon under the banner of “constructioneering” aimed to close the last mile between engineering intent and machine control on the jobsite, aligning survey control, design surfaces, and construction equipment. In the subsurface domain, Keynetix (OpenGround) strengthened geotechnical data management, centralizing borehole and lab information so designers and analysts have authoritative subsurface context.

Bentley also expanded its simulation depth with the acquisitions of PLAXIS and SoilVision for geotechnical analysis, improving the ability to model soil-structure interaction, slope stability, and consolidation. The addition of Seequent—bringing Leapfrog’s implicit geology modeling and an ecosystem serving mining, renewables, and groundwater—extended the reach into the Earth sciences. These moves reflect a consistent vertical-integration logic: pull critical physics and ground truth into the same governed information spine. With the 2020 IPO on NASDAQ (BSY), Bentley secured capital for continued expansion while declaring, in market terms, its identity as an “infrastructure engineering” company. The public listing reinforced a long-standing signal to owners and governments: stability and stewardship are strategic, not incidental.

Standards and owner-operator focus

Standards work underpins longevity. Bentley engaged in initiatives like IFC Alignment and in OGC forums to ensure that infrastructure semantics—alignments, sections, linear referencing, coordinate systems—are not vendor-specific. The goal is to let models pass from design to operations without losing the meaning of stationing or the provenance of a cross-section. In parallel, Bentley emphasized Product and Manufacturing Information (PMI)-like approaches for civil, pushing toward model-based deliverables where sheet sets become views on authoritative geometry, not the other way around.

Owner-operators prize three capabilities:

- Long-term fidelity: formats and schemas that remain usable across decades, mirroring the asset’s life.

- Change provenance: the ability to audit and certify what changed, when, and under whose authority.

- Governed collaboration: a common data environment (CDE) that supports compliance, security, and multi-party contracts.

Conclusion: lessons from Bentley’s infrastructure-centric path

Focus matters

One of the clearest lessons is that focus compounds. Bentley’s decision to center on roads, rail, water, utilities, and owners created a differentiation that endured against general CAD competitors such as Autodesk’s Civil 3D and the broader Hexagon/Intergraph ecosystems. While others optimized for breadth or architectural workflows, Bentley optimized for the gritty details of civil geometry, corridor rules, survey control, and owner deliverables. This translated into products and practices tuned to linear assets, right-of-way complexities, and the interplay between model geometry and regulatory approval.

The advantages of focus include:

- Vocabulary alignment: product roadmaps use the language of DOTs, railways, and utilities—stationing, superelevation, pressure zones—reducing context loss.

- Lifecycle coverage: tools span planning, design, analysis, construction, and operations, so handoffs are governed rather than improvised.

- Trust capital: promises around DGN stability and ProjectWise governance built confidence among conservative adopters.

Data longevity beats short cycles

Another durable lesson is that data longevity outperforms short feature cycles in infrastructure. The stability of DGN V8, combined with the governance of ProjectWise and the change intelligence of the iTwin Platform, created a foundation where information survives organizational churn, toolchain diversity, and regulatory scrutiny. In sectors where assets are financed over decades and maintained under strict regimes, the cost of data loss or schema churn dwarfs the delight of a transient feature. Bentley’s insistence on forward compatibility, explicit element IDs, and disciplined schema evolution means that owners can keep using older models without expensive migrations.

This strategy enables tangible advantages:

- Continuity: archived designs remain interpretable and queryable, supporting maintenance and expansions.

- Automation: scripts and checks built around stable schemas do not break each release, compounding productivity.

- Assurance: auditors and certifiers find consistent provenance, bolstering compliance and reducing risk.

Vertical integration wins

A third lesson: vertical integration across modeling, analysis, reality capture, construction, and operations is not a luxury; it’s a necessity for infrastructure reliability. Bentley’s acquisitions—Haestad Methods for hydraulics, STAAD and RAM for structures, SACS for offshore, SYNCHRO for 4D, PLAXIS and SoilVision for geotechnics, and Seequent for subsurface modeling—stitched physics and field truth into a single governed spine. The ability to federate models from these domains, run analytics, and trace changes creates a resilient delivery system. It does not demand a single monolithic model; it demands synchronized, queryable twins with clear responsibilities and ties between them.

The integration pays off in several ways:

- Closed loops: design changes propagate to analysis, schedules, and inspections with traceability.

- Context fidelity: reality meshes and point clouds ground design intent in the field conditions that matter.

- Decision quality: owners can compare scenarios with consistent cost, risk, and performance metrics.

What’s next

The road ahead will likely blend AI, open ecosystems, and measurable outcomes. Expect AI-assisted civil modeling that converts survey and reality capture into corridor concepts with rule-based geometry, automates standards checks, and suggests staging sequences based on historical data. Trustworthy digital twins will tighten ties to sensors—structural health, environmental monitors, and operational systems—so that models remain calibratable and predictive. Carbon and resilience analytics will shift left into concept and preliminary design, supported by libraries of materials, methods, and performance data that quantify tradeoffs. And open/cloud platforms will continue to abstract away file boundaries, letting owners, engineers, and constructors co-author the infrastructure graph with clear provenance and permissions.

Key shifts to watch:

- Standardization of civil semantics in open schemas (e.g., alignment and linear referencing) that enable tool-agnostic workflows.

- Expansion of low-code/no-code capabilities atop iTwin-like APIs so agencies and contractors can tailor audits, dashboards, and automations without bespoke development.

- Integration of construction machine data, schedule actuals, and cost performance into the same twin, enabling continuous calibration of plans versus reality.

Also in Design News

V-Ray Tip: V-Ray Displacement: Tessellation vs Vector — Selection and Tuning

March 11, 2026 2 min read

Read MoreSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …